Places Family Grief

All That I Can’t Carry

The life of my Lolo and my family in the Philippines is a deep reminder that people live full lives there and places like it, across the globe.

“ . . . so that he can go on without ever putting the box down.” —Jack Gilbert

*

One of the enduring images of grief that I hold is from Jack Gilbert’s Michiko Dead , where Gilbert describes grief as a heavy box that someone shifts, little by little, providing rest for the arms and then the thumbs and then the shoulders. Eventually the cycle starts again, keeping the parcel aloft.

I wish I could remember everything about when I was told that my Lolo—“grandfather” in Tagalog—passed away. That day felt like a blur; the news serving to vignette my eyesight such that all I could see was the phone in my hands after speaking with my mother. When I think about that moment on the phone, I always feel that same sensation of space suddenly opening up underneath me.

By the time my Lolo passed, we had not really spoken for some time. Part of that is due to the general logistics of having your family halfway around the world: I am bad at time zones and have only recently gotten good at remembering the approximate time difference between Los Angeles and Manila. Knowing my Lolo’s daily schedule and if he’d be available during the hours we were both awake added another difficulty.

I left the Philippines for America in 1988, at the age of five. I did not return home until 2002, after my family and I were naturalized as citizens of the United States. Fourteen years worth of landline calls are all we had up until the point we returned for a visit.

My few memories of living in the Philippines are rooted in my mother’s family and, thus, to my grandfather. We lived in a narrow but tall home that housed my family and the families of my mother’s siblings. It was the house that my mother grew up in, as part of a compound that also held structures for my brother’s siblings and their children. All on a plot of land whose footprint might be about the size of a modest corner store on a typical main street in America.

I remember the smell of fresh-baked pan de sal and the voices of vendors selling their wares on the street. I remember our home was so filled with life and people that I didn’t have to travel far at all to spend time with my cousin; he lived on the floor below mine. My mom’s cousins owned a sari sari store—akin to a convenience store—across the street. Even the sounds of the roosters crowing and the trisikletas or jeepneys moving around outside our home gave us the sense of clearly being in the middle of things in Manila.

There were similarities, I suppose, to the scenes we encountered when my family moved to California. Our first two apartments were one-bedroom spots, five people often crammed onto full-size and twin-size mattresses smushed together. We had also moved to Hawthorne, a neighborhood in South Los Angeles, that mimicked the sounds and general buzz of our residential part of Manila.

But it wasn’t the same. And each time I touchdown in Manila, that truth burrows deeper into my marrow.

Each of my trips back to the Philippines act as opportunities for me to collect pieces of my history. Like the actual size of the lot that my family lived on, which looks so much smaller now that I am a full adult. Or the sound and cadence of Tagalog being spoken regularly and without deference to my English-only replies. Or the warmth of all the family members who look familiar by way of photographs and short exchanges over the phone, now smiling and holding me as if distance means nothing.

When we went back for my Lolo’s funeral, I did not expect the novena to take place at a church chapel. My Lola—my father’s mother—had passed about ten years prior, and she lay in the family’s living room until the burial. I expected something similar for my Lolo. Instead, I was confronted with my Lolo lying in his casket and surrounded by flowers. As a member of the Philippine Air Force, he was given a uniformed sentry to watch over him before the burial.

I remember the sense of finality in this moment, the realization that the news that had sapped my body and left me numb was unavoidably real. It was, and lying right there in front of me, intimate and public all at once.

On all our previous trips, my grandfather had done his best to make it feel like the distance meant nothing. He brought us to his office and introduced us to his coworkers. He took time off and acted as a host. Always, he made sure to lavish us with his presence, which was something we couldn’t have from the other side of the globe.

I was worried about the eulogy. I thought about it during the eighteen hours worth of flights over, and while I clung to the roof and handhold of the trisikleta from the apartment we’d rented for the week, and as I approached the casket where my grandfather lay.

It weighed on me because I had not, at least in the traditional sense, grown up around my grandfather. What kind of wisdom had he given me that I could pass on? What kind of offering could I give to a man who lived for me mostly in myth, or else filtered through a telephone line?

What did I have that was of him to share?

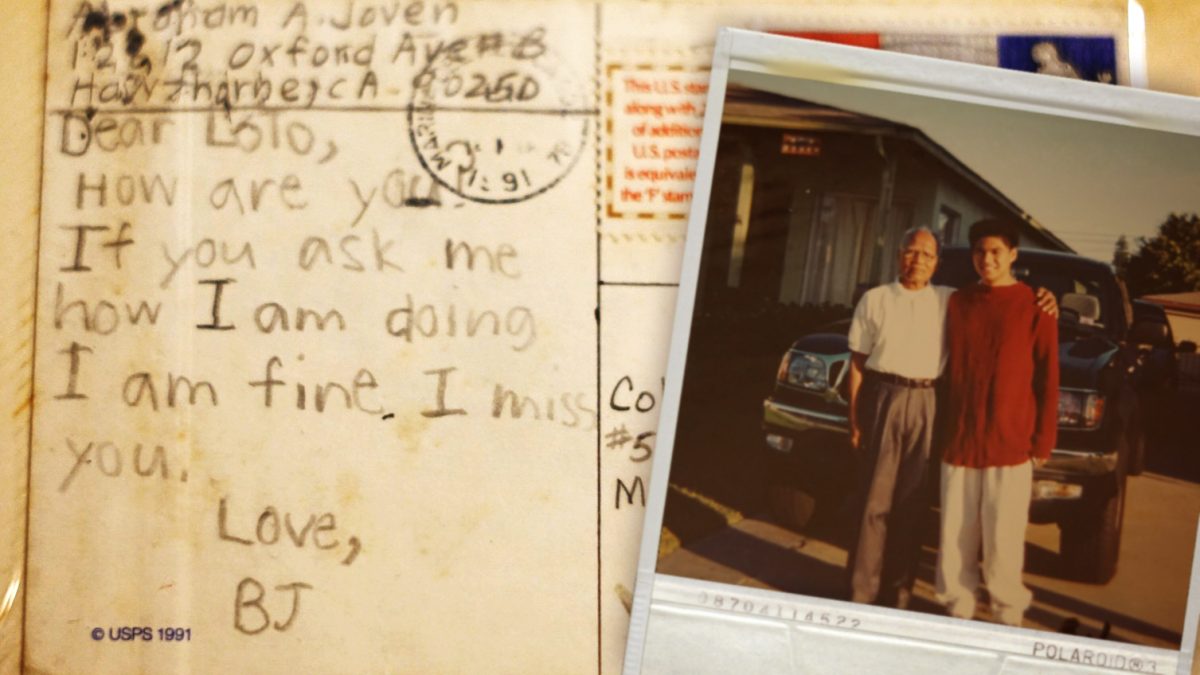

I can’t remember which day it was on our trip because everything seemed to meld into one long day—a by-product of such a short trip compounded by the emotional toll of it all with my one-and-a-half year old daughter in tow. But I remember that, at one point, someone brought out my grandfather’s photo albums and scrapbooks.

Decades and decades of family photos were all there. I saw some from when I was a child, before we’d moved to Los Angeles. I saw one with him carrying my younger sister on his back. As we moved through the years, I noticed how suddenly none of my close family members were in any of the photos.

I saw my cousins in various stages of growth, all with my Lolo. I saw him holding his first great-grandchild in his arms and cradling him with love. I instantly felt a pang that he’d never got to hold my daughter. That he’d missed out on our birthdays. There was physical proof of the giant Lolo-shaped hole in my personal history.

Then someone called out to me, holding a different photo album. In it, I saw photos I’d taken from a study away program I did during my junior year in high school. Based in the East Coast, it was the first time I’d been away from home and the first time I’d traveled on my own. I remember excitedly taking a camera that was my grandfather’s—a Kodak 110mm film camera—and snapping as many photos as I possibly could. My mom made duplicates of those photos so that she could send them home to my Lolo. He’d saved every single one.

My heart skipped a beat when I flipped the pages and found a postcard. It was in my childhood rickety handwriting, a postcard I’d sent to him, asking how he was and letting him know I loved and missed him.

Instantly, I felt I’d finally found the thread I’d been meaning to pull on. Instantly, I’d felt—just like those many years ago—that the distance between him and I, the space between the mortal and ethereal plains, were nothing. He was here with me. He’d always been.

*

I remember sitting at a typewriter while in middle school. I had used it before to type out the various panels for science fair projects and book reports during elementary school. A year from this point, I’d be able to talk my mom into getting our first computer, but then, back in 1995 or 1996, this was all we had.

I was working on a letter for my Lolo. I’d sat down and, over the course of an hour, worked out exactly what I wanted to say. I remember being worried about using the corrective tape—it was so expensive and my mom ground into my head not to be wasteful with it—and managed only a handful of corrections.

When I finished, I gave it to my mom. She read it, smiled warmly, and then tenderly stroked my face. She told me that I reminded her of my Lolo because he rarely drafted his work. That, when he set himself down to write, he would self-edit as he went, constructing his completed work on the fly.

It’s a small thing—and, if we’re being honest, a thing that as a writer I’m not 100% married to because, hey, drafting is important!—but it meant the world to me to have this connection with my Lolo. That I was carrying this very real part of him within me.

I think I would have recognized the things that bound my Lolo and I, like the desire to tell stories and chronicle them, whether by written word or through images, sooner if we’d lived together. But having it this way is still meaningful.

*

As I readied myself for the memorial, and for my part in eulogizing him, I wanted to focus on the things I was grateful for: the time he willingly gave to his grandchildren, the way he seemed to unify the family, how he always treated us all as precious parts of his own life. But looking out at my family gathered in the chapel, I was keenly aware of what I’d lost in the move to America: time with him.

Time spent with my Lolo and aunts and uncles and cousins. Time to learn the culture of my heritage in a way that is so intimate as to feel the history of the islands flowing through my veins. Time among the cherished sights and sounds and smells that still feel like home to me, even after all these years and over all that distance.

I know that it might sound weird to speak so lovingly of a place and a people that the American conception has led many to believe as disposable. Or, at the very least, as merely a tragic migration story that points to an inhabitable home.

But the life of my Lolo and my family in the Philippines is a deep reminder that people live full lives here and places like it, across the globe, every single day. That the randomness of being born on a particular spot on the map would not render my everyday existence to being only identified with toil, struggle, or the desire to flee. And to recognize that the presence of joy and love is not foreign in the homes of my people. Because while I’m grateful for the opportunities I’ve received and the life I’ve built in America, the idea that there was an inevitability to it happening here and not there does not preclude a grief in losing all that could have been.

Because even beyond recognizing the void of all I’d lost in that move is the deep knowledge that if my parents hadn’t had the luck of getting work in America, facilitating our move, there’s no reason to think we wouldn’t have found a life worth living back home. I see my cousin, living his dream as a coach for a professional basketball team. I see the photos of another cousin’s daughter, a few months younger than my own, and I’m overwhelmed by the light in her eyes.

The thing about migrating, regardless of wealth, is that there is an unavoidable paradox: One has many real reasons to stay, but is pulled away anyway.

It’s interesting that Gilbert uses a box as a metaphor for grief, because I’ve recognized so much grief in the process of moving. The idea of packing things up in boxes fills me with intense anxiety. And with my Lolo’s death, I am made immediately aware of all the things that cannot be neatly packed away.

I’ve come to see Gilbert’s Box of Grief as a box containing memories, moments of love. That must be what we cling to when people pass. And my thinking is that no one complains about the weight of the love they’re carrying, even if it’s heavier on certain days because the ones who’ve helped fill it are no longer there to help shoulder the load.

*

Ultimo

After Jose Rizal

“Farewell,” I imagine you said to your daughter.

On the part of the tongue that goes wide

Of time and right back into your arms.Jay . . .

My daughter, your apo, is growingFarewell

And know that loving