People Fans

Enter the Mars Volta

“Omar and Cedric turned center stage into a two-man prog version of Soul Train.”

Summer 2005 began with the ribbon-cutting act of painting my new co-op bedroom. With two housemates and Ghostface Killah’s entire discography on rotation—including the Theodore Unit tape 718 —we lathered sky blue onto my walls, the only clouds in sight arising from the small starter pipe and child-safety-unlocked Bic circulating between us. I was twenty-one, finishing my third year towards a history degree at UC Berkeley, co-running the campus poetry slam, and gigging as a spoken word poet and performer. I quickly grew tired of some of the more banal spoken word performance paradigms, where a couple of my loudest, most lyrically playful poems were performed in a short allotment of time at an event like-minded in beliefs but otherwise devoid of poetry. Or something at a school, teaching workshops or guest performing, standing before a McClymonds High School gymnasium full of West Oakland youth, feeling once again like a circus act exposed on a talk show for fathering recycled slam poems.

That summer, my already knee-jerk antisocial behavior grew sophisticated. Mental maps of every side street on all four sides of campus developed. The road less traveled was literally the only one I’d walk around town, the metaphor unable to describe the many muddy inlets around Strawberry Creek and the basement hallways-turned-pathways that chiseled my psyche into a well-formed social anxiety. On nights when I wanted to avoid house co-op meetings, I’d climb the fire escape from the front entryway up four flights to my bedroom window.

A breakup accelerated my hermitage. When we split, it felt tectonic. I called us quits before jumping seamlessly into a friend’s getaway car straight down 880 to Oakland International Airport for one of several pilgrimages home to the far reaches of Los Angeles County. Returning to Berkeley a co-op-wrecker, I immediately hid inside my newly painted cube of sky.

Without class or homework, life was spent between my blue corduroy couch and working at the library, consumed, like the rest of the student body, with first-generation iPods and curated iTunes playlists and lazy nights drinking Lagunitas on co-op rooftops. When I wasn’t working or at home, I’d go to Moffitt Library, the university’s main stacks, and head downstairs to watch movies in these small cardboard-partitioned viewing rooms, “with other people” in that sense, but otherwise sitting, headphones on, alone. Listening to one of my favorite bands at the time, the Mars Volta, I began to watch films that they recommended—Jodorowsky, Buñuel, Bergman, Fellini—and other like-minded directors of the era, including Cassavetes, Malle, and Kurosawa. I began jotting library call numbers, creating a film watch list in my journal that I progressively started checking off as summer progressed. Occasionally my friends, who lived a block up from the co-op, would take me in for dinner and movie watching, checking off the Janus Films’s catalog one VHS oddity at a time. Otherwise, my summer was set to Stealth: work and cinemas at the library all day, climbing the fire escape into my bedroom each night.

Thankfully I lived inside a cocoon. Co-ops are micro communities that, at their most functional, can flow like a well-oiled (gasp) community. Maybe it was the implied free love, yellow-let-it-mellow stereotype of co-opers around campus that all of us tried to live up to in some regard. A campus-wide collective of purportedly cordial and progressive humans on a four-year live-in-study program provided endless cereal of the sugary and hippie varieties, kegs on the roof, organic watermelons injected with the cheapest fifth of vodka from Seven Palms Bodega, all while kicking out members of the house who threatened physical violence while high on not-so-prescribed prescription meds.

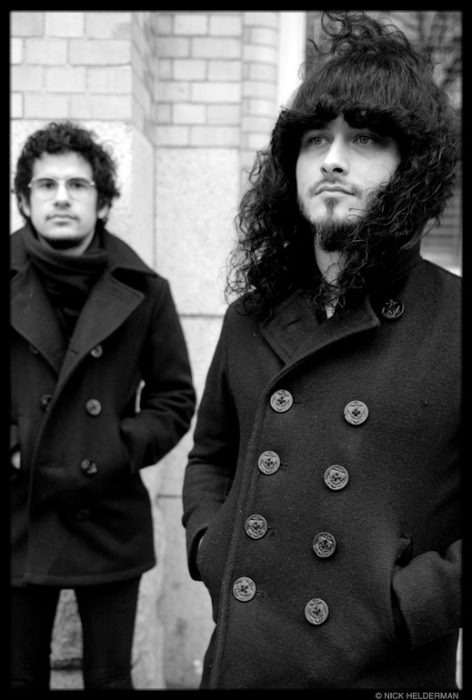

Co-ops impose the idea of The Whole onto you and your individual responsibilities as a resident. For the Mars Volta, the leaders were clearly identified as the dual heads of Omar Rodriguez-Lopez and Cedric Bixler-Zavala. Representing the band in press photos and interviews, they were the iron fist against which the Volta’s creative engine plowed through non-radio airplay and shitty Pitchfork reviews to Grammy wins and sold-out tours.

My reclusive summer was interrupted that June when my housemate and I decided to see the Mars Volta up the street at the Greek Theater, touring in support of their sophomore album Frances the Mute. This massive stone outdoor amphitheater tucked in the Berkeley Hills was filled with the proverbial diaspora of brown/black rockers all in one spot. It was like the opening scene of The Warriors where all the boppers of New York gathered to hear Cyrus speak. That is, if Cyrus were really into twenty-minute song performances that combined Johnny Pacheco-era salsa with Can and The Birthday Party, all collectively scoring a Fellini film live for a stoned Berkeley crowd.

All of the Volta boppers entered the Greek with their own styles and crews en tow—green Army jacket collars tucked beneath overgrown afros and mutton chops; flower-patterned summer dresses accented with white Chucks—someone in each group assigned the task of gatekeeping subway tokens for the crew members—or rather, the Ticketmaster Will Call tickets. The Volta was our prophetic Cyrus, decreed “the one and only” and we, like the Warriors, travelled to the Volta’s shows to “have a look for ourselves.” Each crew had heard their own story of the power of the Mars Volta’s performances, and anyone who missed out on their electric predecessor, At the Drive-In, was making up for lost time.

*

The El Paso, Texas-based quintet At the Drive-In, modern rock’s perceived saviour of 2000, arrived as a perfect nexus founded on relentless DIY-touring and multiple small-label releases before finding mainstream supporters like Rage Against the Machine and the Beastie Boys, the latter signing the group to their Grand Royal Records imprint, sewing the seeds for the release of the instant classic Relationship of Command . They were synonymous with raucous live shows fronted by a duet of massive afros: lead singer Cedric Bixler-Zavala and lead guitarist Omar Rodriguez-Lopez. Their physicalized energy stood naked and in contrast to the Iowa-stitched clown masks or backwards red Yankees caps of their modern rock peers. Calling them “road veterans” would be an insult to the massive catalog of shows At the Drive-In executed between studio recordings of songs written in the back of Econoline vans, touring with nascent incarnations of Jimmy Eat World, The Get Up Kids, and later The Murder City Devils, Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Japan’s Eastern Youth. By the time mainstream radio and fans with the money to afford Ticketmaster fees appeared, the band was summiting its own zenith with nothing left in the tank, breaking up less than a year after Relationship of Command ’s groundbreaking release.

The album’s lead single “One Armed Scissor,” a rallying cry for its time, featured Cedric’s ability to bend tenor notes of abstract images and Burroughs allusions into legible melodies throughout the song—“banked on memory / mummified circuitry / skin graft machinery / sputnik sickle cells in repeat”—and showcased the tonal depth of a band otherwise known for chaos, however many times they discouraged slam dancing before their shows. The song’s music video fanned the lore of a frenetic, agitated quintet. On live televised national performances, like NBC-era Conan and Letterman, Cedric is part MC5 meets James Brown meets Jello Biafra, leaping from kick drum to center stage, grabbing his already airborne microphone midair in time to sing the next line, followed by hand plants against the stage and stallion kicks to the sky. At the Drive-in was fanfare fodder incarnate: original, unpredictable, and relentless.

ATD-I shows were different not only for the music but the crowd, a greater margin of brown kids in the audience reflecting the same on stage. In Los Angeles, fanfare Venn diagrams could be broadly drawn across the ATD-I, Rage Against the Machine, and System of a Down’s core modern rock audiences. One thing unique to those bands is their different uses of rhythms: from System’s schizophrenic stop-on-a-dime adrenaline shot to FM radio; Rage’s boom-bap wrapped in Molotov cocktails and guitar discords; and ATD-I’s off-punk angular groove evolving into a cathartic rage. Along with notable albums that year from A Perfect Circle, Deftones’s White Pony, and the still-innovative Kid A from Radiohead, ATD-I stood at the forefront of a collection of disparate bands that collectively pushed the definition of “rock” in 2000.

I saw ATD-I on the first and last dates of what would be their final 2000 American tour in support of Relationship of Command . The tour’s bookends were in Los Angeles County, first in my hometown of Pomona at The Glass House, and finally in Hollywood at The Palace on Vine (now Avalon Hollywood). While the Pomona show was marked by a tightly-rehearsed set, their Palace performance seemed ragged and drained. Months later, after a busy European tour, the band announced an indefinite hiatus, a nicer public breakup note to fans and industry alike. A fork in the road appeared, separating Omar and Cedric from the three remaining ATD-I members who’d form the initial core of Sparta. Fans eagerly awaited what “rock” band would emerge from Omar and Cedric’s side of At the Drive-In’s ashes.

*

Enter the Mars Volta. A name inspired by a Fellini concept towards filmmaking, the Volta took flight after the success of their initial Tremulant EP (2001) with their widely well-received 2003 debut album De-loused in the Comatorium . It was immediately clear that the death of At the Drive-In was necessary if only for the Volta’s sheer existence, let alone their music and subsequent popularity. Frances the Mute itself debuted at number five on the U.S. Billboard charts, selling over 465,000 copies in just a year after its release. And this, for a so-called “prog rock” album. I imagine Omar and Cedric walking into their record label, proclaiming “CAN YOU COUNT SUCKAS? I SAY THE FUTURE IS OURS IF YOU CAN COUNT!”

At the Greek, my friend and I sat in denim jackets on stone seats composing the theater’s outer rim, beneath the lawn and above the symphony pit. The sun was setting from San Francisco. My friend asked if DMX would make a cameo, based off a story I told him. When I was fifteen and waiting in line for that second ATD-I show at the Palace, across from the Capitol Records building, DMX filmed a music video right on the strip, towed by a tow truck while “driving” a lowrider southbound towards Hollywood Boulevard, with an entire line of ATD-I and Murder City Devils fans, and a sizeable showing of Japanese-American fans of the Osaka-based opening act Eastern Youth, all raising their crossed arms making “X”s, saluting the growling rapper, his hand forming a peace sign to us as he crawled by with his other hand glued to the wheel.

Since At the Drive-In, Bixler-Zavala and Rodriguez-Lopez’s subsequent bands spawned shows with lineups that forced multiple different communities to collide. While touring for their pre-Volta dub project De Facto , the group interrupted otherwise punk/hardcore bills of Bratmobile and Pretty Girls Make Graves with their tributes to Augustus Pablo and traditional dub. The initial Mars Volta’s U.S. tour was opening for indie rock favorites The Anniversary with Mates of State. On the Volta’s headlining stint in support of their debut album, spoken word artist and musician Saul Williams was their opening act—reading a single epic poem from a scroll as long as the venue itself—as well as noise band and Gold Standard Laboratories label mates Kill Me Tomorrow! At the Greek that night, everyone and everything was cool. As Cyrus stated in his opening monologue, his summit brought together “The Moon Runners right by the Van Cortlandt Rangers. Nobody is wasting nobody.”

The crowd increased in the pit where a stage two weeks earlier was filled with undergraduates receiving degrees, their parents blaring air horns from an orchestra pit now filled with smoke, long hairs, and red lipstick. The sun still peeking from San Francisco progressively faded over the East Bay as the show commenced. Drummer Jon Theodore, keyboardist Ikey Owens, and bassist Juan Alderete formed the early Volta’s core. This tour also introduced Marcel Rodriguez-Lopez and multi instrumentalist Adrián Terrazas-González, who incorporated flute solos, saxophone, and percussion to an already dense ensemble, and made it work. Former ATD-I and Sparta member Paul Hinojos also joined as second guitarist and sound manipulator, a role vacated after Jeremy Ward overdosed in 2003. After Long Beach’s own DJ Nobody opened, the soundtrack to A Fistful of Dollars by Ennio Morricone blared over the PA, introducing the band to a stage flanked by large stone columns. Behind the band, massive illustrated backdrops of two well-beaked murderous birds facing each other in a mirrored dual by Gustave Doré or Max Ernst.

The audience’s silent question of how the jam-driven Volta would translate their new five-song, seventy-seven-minute long album into a live show was answered with the first song of their set—their previous album’s longest song “Drunkship of Lanterns”—before launching into fan favorites “Concertina,” from the still-amazing Tremulant EP, and “Take the Veil Cerpin Taxt,” whose amphetamine-driven slithering riffs propelled the band’s physicality: The sweat flying from Theodore’s kit, Alderete’s punctuated bass lines dipping his neck in and out in front of two massive bass amps, each draped in Mexican flags, while Omar and Cedric turned center stage into a two-man prog version of Soul Train. Early in the set, Cedric announced himself to the crowd with a hand-plant-to-stallion-kick, his heels kicking the sky, before later sprawling himself to the ground, his arms crawling his otherwise limp body towards Ikey Owens’s keyboard rig.

Standing on the wave created by Volta’s long songs was like riding a threaded diasporic DNA braid straight to Pangaea by way of Long Beach, Harlem, Bayamón, Chiapas, the depths of the Atlantic, and Nigeria. Owens’s organ and the thundering rhythm section truly engendered a church-like setting through the bodies of each audience member-turned-witness, the congregation mesmerized by the Volta before us. Amongst an otherwise berating set, moments of calm were found in the jazzier breaks within “Cygnus . . . Vismund Cygnus” or the band’s solo jousts in the highlight performance of the night, “L’Via L’Viaquez,” Frances the Mute ’s lead single. The surprisingly straight forward play of Theodore fuels the song’s entirely Spanish verses broken into times-running-out! transitions that weave an action flick’s suspense with a salsero ballad, seemingly in mourning of the L’Via described in the song.

These slow dance sections generated more cheers from the crowd than any frenetic part of the song, the whistles and cheers increasing as Ikey performed the solo Larry Harlow executes on the studio recording, with Omar adding his signature solos to those recorded by friend John Frusciante. The addition of Adrián Terrazas-González’s amazing percussion, brass, and flute play added an entirely new dimension to the wide spectrum of sounds the Volta displayed in their sets. Cedric’s voice is a hushed warning seemingly sent from beneath the Pacific, the words heavily delayed and signifying the spirits of L’Via herself.

Sitting at the Greek that night, I closed my eyes tight enough to feel my body being guided into the front seat of a classic foreign car; I can hear the pull of the guitar solos turning with the classic car in which I sit, windows down, blindfolded with red scarves, skipping and weaving across dried aqueducts with a strange blindfolded mute behind the wheel, fully living the Frances the Mute cover art by Storm Thorgerson. The cover implies what songs like “L’Via . . . ” create for the listener: a journey through a world only the Volta can soundtrack and narrate. The band needed additional percussion, brass—a goddamn flautist—to avoid the sonic trappings of At the Drive-In and other glass-ceiling-tapping bands, with this era of the Mars Volta arguably most in tune with the sounds, phrases, and rhythms neglected by their predecessor.

It is this rebellious spirit of congas and brass and keys and flags waved proudly on stage that made us, the audience, feel so much a gang before a Cyrus-like pulpit. My transition from At the Drive-In, De Facto and the Mars Volta, was one from sobriety to cannabis cards; from complete virgin to sex shop value program cards. We were the sometimes grimy kids in green army or black denim jackets running from the Fillmore through the projects back to BART, sweat on face and mud on shoes , frightening the ball-gowned prom attendees leaving a posh SoMa club on the way back to Frat Row.

Much like the clarity of Cyrus’s vision for planning a five borough takeover by way of uniting each gang through a general truce, we came to the church of Volta to discover the progressive sounds that inherently deterred most assholes from coming to shows like this in the first place. However popular the band grew, it was too weird, too niche, too brown, too black, too everything. It was “our turf,” to quote Cyrus, our general demilitarized zone against the rest of modern rock’s banality. Every second of every twenty-minute song played live, or every five-song, seventy-minute album released to Billboard success by the Mars Volta, was our way of uniting what lines exist between us, to create a united vision like Cyrus’s own, and to enjoy each song, each album, each show as the true miracles they are, because “miracles is the way things ought to be.”

My fanfare for the Volta waned with the loss of original drummer Jon Theodore, and a directional shift towards larger, longer rock operas of Bedlam of Goliath and later the pop tunes of Amputechture . Seeing the Volta that summer for their Frances era reminded me of the power of being obsessive; of drawing from the sights, sounds, rooms, and people that make me stronger.

We left the show in a blur, ears ringing, a sense of pride for the elated exhaustion those endorphins weighed on our bodies walking back home. My friend and I did the standard geek out play-by-play: Which parts of the songs were extended, improvised, the songs they did or didn’t play, the background art, whether or not Ikey’s keys were turned up enough, and seeing Paul on stage with the Volta for the first time.

Walking home down Ridge Street towards Euclid, I recounted a film I’d seen a few days before the show, Luis Buñuel’s final 1979 film, That Obscure Object of Desire . In the final sequence, after watching a woman hand stitching (and subsequently bleeding) in a storefront window, Fernando Rey and Á ngela Molina walk off into the distance of an indoor mall, before an extremist-caused explosion consumes the screen and abruptly ends the film. Though this was Buñuel’s statement on his fears of extremism rising in Spain and France, it also highlighted the crux of his creative career: That in order to create, you must destroy. The explosion—the danger of playing so loud the amps break or the cherry at the tip of every joint in the crowd—goes out in an extinguished awe of the moments before us, the solos where every note is hit perfectly on pitch, a guitar that never goes out of tune no matter how many times it’s slung abusively around a sweating body, the conga and drum mics keeping the round sound of fire-tuned skins covered in flags and sweat: No stage can handle that possibility, that magic some of those initial Volta shows brought, without some form of combustion.