People Generations

A Separate Dream: Faith, Family, and Knowing When to Let Go

When a hard line on intermarriage leads to exclusion.

My aunt had encouraged my interest in dance; at her suggestion, I visited her and my uncle in Brooklyn during almost all of my college breaks to take modern dance classes in Manhattan. I recently found a note that she sent me during my junior year, which read: If you had not majored in dance, I am not sure we would have had the chance to find our bond, as I feel we have.

During those visits, she taught me how to roast a chicken in orange juice and paprika, to cook a quiche without a crust, with spinach, eggs, cheese, and sautéed onions, and to steam bulgur with chickpeas. I could not help but compare her to my mother, her sister, who did not cook, and who often expressed that she’d wasted any domestic inclinations on her short marriage to my father. My aunt kept cinnamon rolls and corn muffins in a glass pastry dome on the kitchen counter. The clockwork nature of her home filled me with energy and purpose. My three cousins had many friends, and cousins of the same age on my uncle’s side. I attended my younger cousins’ weddings wishing that I were again nineteen, twenty, or twenty-one, with no occasion to separate from a shared history.

Almost immediately upon relocating to New York from North Carolina, where I’d landed with friends after college, I became a regular at my aunt and uncle’s home for Friday night Shabbat dinner, the Jewish New Year, Chanukah, and the Passover Seder. My aunt and uncle are part of an Orthodox Jewish community in south Brooklyn, and observance sets the rhythm of their household. Such tradition was not a consistent part of my life while I was growing up, both because my parents divorced when I was quite young and because their own relationships to Judaism were private and intermittent.

On a Friday night at my aunt and uncle’s home, white tapers are lit at sundown, and burn in sterling candlesticks on the kitchen counter. The dining table is covered with a sateen pink tablecloth, a large crystal vase filled with white lilies set in the center. Also, two crystal water pitchers, two loaves of challah bread underneath a blue velvet cloth cover, a silver wine cup for Kiddush, the blessing over wine, and a small silver pitcher on a small silver plate over a small silver bowl, to be passed from person to person at the end of the meal, for washing the hands. A chandelier hangs over the center of the table, the carved facets in each teardrop crystal holding pastel green, pink, lavender, and blue light around the bead.

Twelve years after first moving to New York, Derek, who is now my husband, and I moved in together. I’d struggled for a long time in relationships, often holding onto painful entanglements. The first Friday night in our new apartment, seated side by side at our dining table, I silently recited the Kiddush, the blessing over the wine, and the Ha Motzi, the blessing over the bread, to myself. I might have said these words aloud, but it did not occur to me that I wanted to say them at all until we were seated, with bowls of pasta and sautéed mushrooms before us. My observance had not transcended my aunt and uncle’s home, but I suppose I wanted to share these feelings, this type of home, with him.

By that point my oldest cousin, a father of three, had taken a hard line on intermarriage, and Derek is not Jewish. While my aunt initially attempted to include us in holiday and Shabbat gatherings when he was not around, she struggled, caught between her son’s expectations and my hurt feelings. I have since watched our relationship gradually diminish, and disappear.

*

In the second section of “Minus 16,” a contemporary dance choreographed by Ohad Naharin, eighteen dancers in black suit jackets, hats, slacks, and white button-down shirts stand in a semicircle, facing the audience. A metal folding chair is set behind each dancer. “Echad mi Yodea” begins, a song that dates back to sixteenth century Eastern European Jews, the Ashkenazim; the title translates to “Who knows one?” The thirteen verses are an accumulative list of Judaic tenets. One is our G-d in heaven and earth . Two are the tablets of the covenant. Three are the fathers of Israel. Four are our matriarchs. Five are the books of the Torah . . . Naharin follows the structure of the song choreographically, the dancers accumulating physical gestures as the list builds. The song is traditionally found in the Haggadah, the text that guides the Passover Seder.

My aunt and my mother and I are Ashkenazi. My grandfather, Leon, is from Kovel, which was a Polish city when he was born, though it is now part of the Ukraine. His birth certificate was handwritten in black cursive on a slip of brown paper that could fit in the top flap of a checkbook. It notes his date of birth in 1918 and his given name, Lipa.

Once, when Derek and I were at my grandfather’s dining table in Florida, he said unexpectedly, “I talked to my brother once, before he disappeared. In 1942.” Kovel was a pivotal city for the Germans, as six major railroads went through the town. In 1942, when the city was under German fire, my grandfather’s letters to his family went unanswered. The Red Cross helped him locate a councilman from the municipal government in Kovel, who found his brother, Moshe. In a short phone conversation, Moshe voiced his regret at not having fled sooner. The councilman attended my parents wedding in Brooklyn in 1970. In October of 1942, twenty-eight thousand Jews in Kovel were executed by gunshot, in a quarry.

My grandfather cycled through other memories I’d not heard him mention before that day. When my mother was a young child, in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, she often asked to go to Shabbat services with my grandfather on Friday nights. He went alone, but took her along on Saturday mornings.

*

In the past three years, despite being excluded from family weddings, Seders, Rosh Hashanah meals, and Shabbat dinners, I have reached out to my aunt, uncle, and cousins in ways both casual and heartfelt. I have sent texts on birthdays and emails with kosher Passover recipes, and suggested to my aunt that we meet for lunch. I’ve typed my feelings of loss gently, in emails to my aunt, and directly, to my cousin—who said in return, Unfortunately the examples we must set to enforce the importance of maintaining our Jewish identity is simply a line I cannot cross .

Our wedding occurred during the murky time that we had not so decidedly drifted, and my aunt and uncle were there. Derek and I choreographed a dance to a popular song by Clean Bandit called “Rather Be.” It begins, Oh, we’re a thousand miles from comfort, we have traveled land and sea. But as long as you are with me, there’s no place I’d rather be . My uncle stood between my mother and my aunt and held their hands tightly, smiling, not conflicted nor resigned nor impatient.

But we have not seen them since. We do not hear from them on birthdays and anniversaries, we do not meet for lunch, we do not exchange emails or cards. For a long time, I have been the only one in this scenario who has not let go. But as the secular new year approaches, I feel ready to move forward, to accept our closeness as a thing of the past, which ultimately came with conditions—I feel ready to let go, and make no more overtures. Judaism becomes something to know and grapple with on terms that are entirely mine.

*

I purchase tickets to see Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater every winter because “Minus 16” is included in the repertory. The version of “Echad Mi Yodea” that accompanies this dance, by an Israeli rock band called Nikhmat Ha Traktor, is contemporary and percussive—but the ensemble singing in Hebrew is a return to my early, and shared, family memories. My uncle leads “Echad Mi Yodea” during the Passover Seder at his dining table every spring. On the nights I sat at the table, I was embraced within his family, and within the lineage that tethers it.

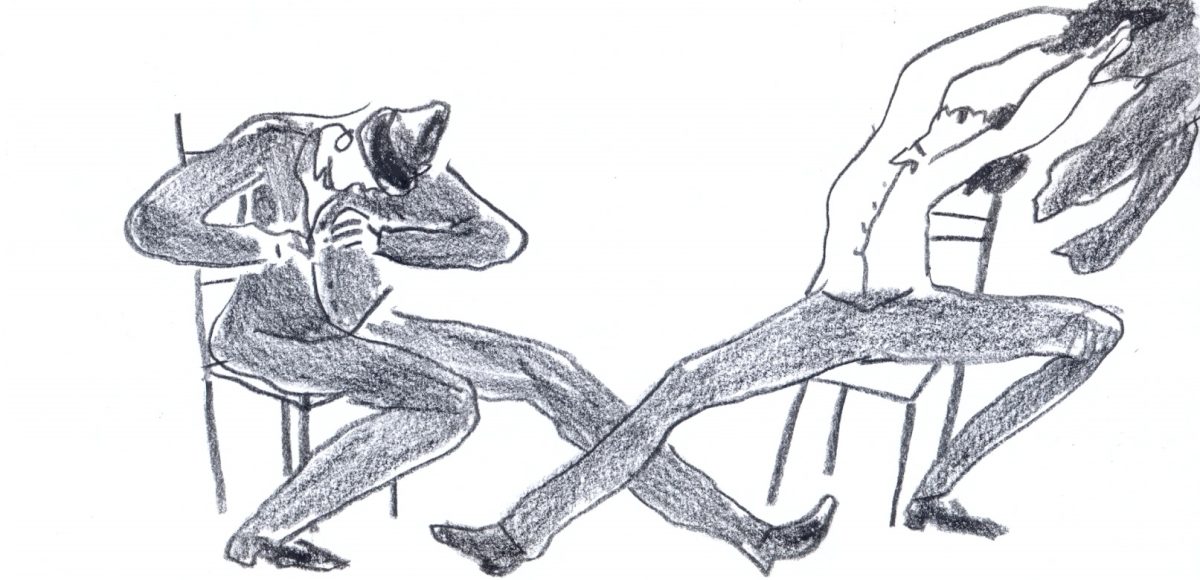

I do not know if I am undone by this dance because these memories are now lost and aching, or because of the sensual and frenetic build of the physical gestures. One by one, while standing before their chairs, eighteen dancers arch backward, their chests opening like split seams. One. Who knows one? One is our God in heaven and in earth. They sit in the folding chairs and lean forward, placing an elbow on a knee. They clench their two hands together to form one fist and drive the fist into their abdomens; they nod frantically; they drop to the floor while still clinging to the rungs of their chairs, kneeling momentarily before springing back into their seats. They shed their clothing. At ten, ten are the commandments , they throw their suit jackets into a pile in the center of the stage. At eleven, eleven are the stars in Joseph’s dream , they unbutton, remove, and throw their white shirts. By thirteen, the attributes of God , they wear only white tank tops and briefs. When the song ends, every dancer is gazing forward, having a separate dream.