On Writing Shop Talk

How Publishing My First Novel at Twenty-Five Almost Ruined Me for Life

I thought I was the exception to every rule about writing being a hard living. I got exactly what I deserved.

I signed my first book contract a few weeks after my twenty-fifth birthday, in late 2008. In my mind, this already contained a sliver of failure, because I had really intended to sell a book by the time I turned twenty-five. Even this goal was a onetime compromise with myself; originally I had hoped to hit the benchmark by twenty-two. I think I had read somewhere that T. S. Eliot had written Prufrock at twenty-two.

(If you hate me already, don’t worry. The humbling is on its way.)

Like all brazen egotists, quivering just beneath my veneer of confidence was the suspicion that all my ambition was, in fact, delusion. I got the call from my agent, I made the teary announcement to my parents, I ate victory sushi with my then-boyfriend (now husband), and then I realized, with panic, that I actually had to deliver a finished book. Adding hubris to hauteur, I had managed to sell my debut novel on a partial manuscript, so delivering a finished book meant sitting down and writing about three-quarters of it. I had never so much as published a short story.

Both adding to and subtracting from my unearned sense of superiority was genre: I had sold a young adult novel, very hot in the post- Twilight era. I felt simultaneously insecure that I would not, as a YA author, be Taken Seriously as a Real Novelist, and convinced that, as someone with virtually no professional literary experience, I was destined to saunter into the YA saloon and class up the joint. Everywhere I went, I loudly reminded everyone how hard it was to write great literature for young readers, that masters like Sherman Alexie wrote YA, that the condescension toward a genre dominated by women was so gendered. All of my assertions were factually correct. And all of them were motivated by my being both high on my own farts and terrified by my own shadow.

Eventually, I did what I had to do: I put my ass in a chair and I wrote the book. It helped that I had just moved to a new city, San Francisco, and had very few friends. It didn’t help that I had a full-time job. But I wrote the book.

In that weird interim that loiters between finishing a book and the book being published, I realized that if I wanted to make a career as a novelist, I was going to have to write another novel. Either the success of the first book taking off or the failure of it tanking was going to make it hard to write, I reasoned, so I had better get writing.

(Spoiler alert: The book did not take off. Have you heard of me? I didn’t think so.)

So I did. By this time, 2010, I was freelancing with some advance money in the bank, so I could afford more concentrated writing time. I started writing another novel with the explicit intent of making this one More Serious, More Adult, More Literary. If I wanted to prove I could be something more than “just” a YA author—as if a YA author were such a trifling thing to be—I figured now was the time to demonstrate that versatility. My words were so large! My sentences were so complex! I had already seen how easy it was to sell a book—six months after finishing my MFA, on a 75-page partial—and I was roundly prepared to sell another, posthaste. Secretly, I suspected that everyone who observed how hard it was to make a living writing books was just bellyaching, or not talented enough. The steady income my parents had always feared my literary passion would forfeit was well within reach.

In early 2011, my agent and I submitted the partial of my new novel to an editor friend at a well-known publisher. No dice. Well, fine, I thought, I suppose I could understand having to write the whole book. But then I got busy writing and producing an independent film, an experience which, while transformative and wonderful in many ways, also made me yearn for a quiet room in which to write alone. I didn’t get my wish until we’d finished and premiered the film, in summer 2013. I sequestered myself in a small cabin in rural Wisconsin for as much of that summer as possible, went slightly insane, and got the second novel rolling again.

Then, on Labor Day weekend, I discovered I was pregnant. This was exactly the deadline I needed to self-motivate, and I turned in the final product—or what I then thought was the final product, but was actually a first full draft—in April 2014, mere days before my son was born. This would work out perfectly, I thought—I had done my part of the job, and now my agent could do his while I was on maternity leave.

The book didn’t sell on my maternity leave. It didn’t sell by my son’s first birthday. By then I was writing a lot of essays, too, and had begun to collect them into another book. Around the same time, my agent was menschy enough to suggest that, since he primarily represented YA, my adult novel and essay collection might be better repped by someone else. So I found a new agent in mid-2015, convinced this would be the silver-bullet move. A well-connected go-getter, she has helped me revise both manuscripts, and has sent out multiple full submissions rounds of each. In 2016 we almost sold the essay collection, but the editor who’d expressed such fervent interest ghosted on us. In 2017 we almost sold the novel, but the editor who’d expressed such fervent interest turned out to be too junior to marshal her bosses into funding the acquisition.

And now, here we are, in 2018. It’s almost ten years since I sold my first novel, when I thought I was the exception to every rule about writing being a hard living. I got exactly what I deserved.

*

Though I’ve learned to steel myself against rejection, or always been hubristic enough not to let its sting deter me, there has been an increasing frequency of moments in the last two years in which it’s messed with my head. Between age four, when I started stapling construction paper to printer paper and writing books, and my early thirties, the prospect of giving up really never entered my mind.

Somewhere around the fiftieth rejection of the novel that was supposed to be my great adult debut, though, my confidence started to waver. What if the book never sold? What if I never sold another book at all? Absent the delusional confidence of my twenties, when talent was still all potential and a life was still more future than past, I got better acquainted with some of the hard truths inherent to the writing life: Lots of books never sell. Plenty of people give it their all and never get a lucky break. Talent and even hard work aren’t always enough.

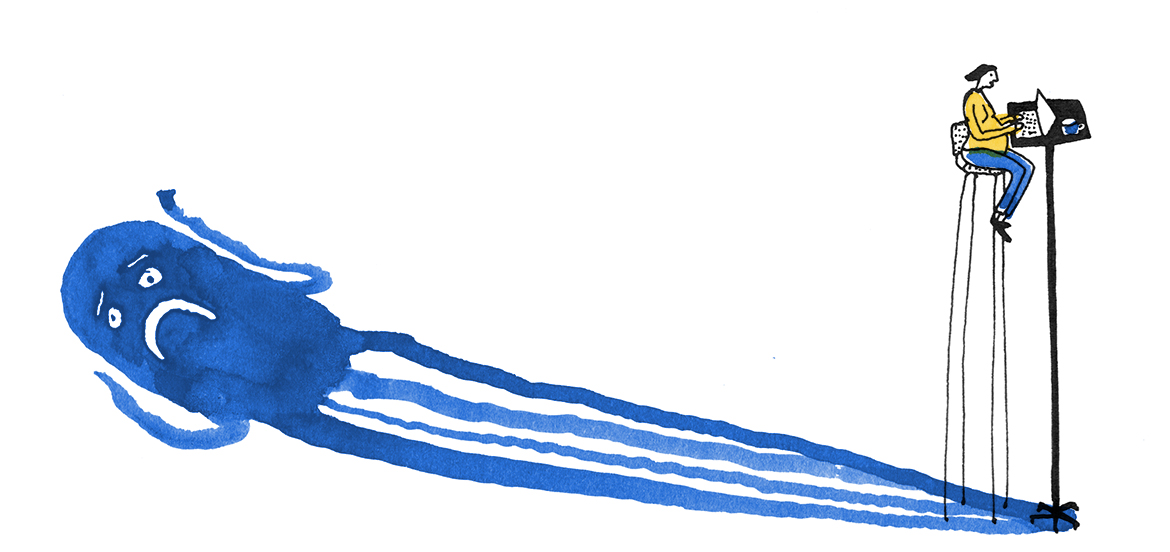

In 2016 and 2017, failure haunted me. It gnawed at me at three in the morning. It distracted me when I tried to work. Why wouldn’t either of my books, the books I’d written and revised and sent out over and over again, the books that were now on their second agent, the books I’d humbled myself before, the books I’d plunged into the depths of myself for—why wouldn’t they sell? Those books were my heart. They brought me to and over the brink of tears every time I thought about them, including now. What the fuck did I have to do to make them enough ?

There was no answer to be found. Every time I circled around these questions I found myself in a new grip of torture, goose-stepping to the sickening drumbeat of I want, I want, I want. There was no work to be done there. There was nothing to eat down there. There was only the howl of my own indecent hunger.

*

These questions— how do I sell these books, why aren’t they enough, how long will it take— were, eventually, unpleasant enough companions to make me seek new ones. So, thank god, I started to ask better questions. Why do I write? Where was that little girl folding construction paper over printer paper and stapling it to make a book? What drove her to do that? What did I need in order to live with the uncertainty of market forces outside my control? What, if not that, could I control?

Considering these questions led me into a mercy that could only flourish beyond the echo— I want, I want, I want— of my own ego. Why do I write? I write because language is my native language. I write because nothing makes me feel better, fuller when I’m drained and relieved when I’m bursting, like writing does. I write because I grew up with a mother who was constantly overwriting my own narrative of myself, and reclaiming that narrative became an act of survival. I write because the page is a space where I am uniquely free. I write because I know that reading makes me feel less alone, and I want other people to feel less alone, too. I write to connect. I write to retreat. I write to feel loved. I write to love myself.

There is also, of course, the matter of keeping food on the table and lights on in the house. And writing has never been very good at that. But writing novels for the money is, like moving in with a new boyfriend to save on rent, a high-risk, objectively bad calculation. I’ve always had income sources apart from writing: the service industry, the hospitality industry, and whatever you call being married to a more gainfully employable person. I probably always will.

What’s more, it’s also true that as I had been privately bellyaching about not having sold another book, I had made a movie, published a book of poems—a dream even longer and more closely held than being a novelist—and built a reasonably steady literary income writing essays and teaching. (And, oh yeah, gestated and birthed a child.) It’s funny what ego obstructs, all the ways it can find to lie to us. As I’d been bemoaning my lack of luck, I had missed all the ways I was getting extraordinary lucky. And, of course, working my ass off.

Once I stopped asking why won’t my books sell and started asking why do I write, I started sleeping better. I found joy in writing again. I relocated the childlike sense of wonder language had given me when I was too small for anything but books. I realized how unimaginably lucky I was just to have any time and space to write. I realized that I couldn’t chase the success I wanted, which was only the hand-feel of sentences and pages themselves, unless I removed the millstone of false failure from around my neck. Capitalism couldn’t relieve me of that millstone. Only the delight of a little girl stapling construction paper to printer paper could do that.

*

In the darkest weeks of the year, two months from my second maternity leave, I started writing my third novel. I heard its first four-word sentence in my head for weeks and then one day I could see the rest of the story sprawl before me like a body on the beach. I wrote a more painfully detailed outline than I’ve ever written at the outset of a project, trying to protect its incremental growth from the imminent onslaught on my attention span. I wrote a bible of its characters. I created a folder for it on my drive. And I huddled in bed and I wrote the first chapter. And there, in the thrill of a new project’s possibility, I felt free.

Eight months pregnant with my second baby, and on the final solo jaunt of my foreseeable future, I sat in a vintage diner in Los Angeles with my friend Meera eating pancakes and eggs. Meera, filmic co-conspirator, is the kind of friend at the mention of whose name my therapist brightens. She is warm. She is generous. She believes the best in people. She has always shown me a better version of myself.

We were talking about a talented friend who couldn’t write. We were frustrated with this friend. We wanted them to sack up and stick up for what made them who they are, which is writing.

Writing is hard, this friend had said.

In that moment, I had no compassion for writing is hard, even though I have made the same complaint countless times. I had no compassion because I could see in my friend what I couldn’t, in my ugliest moments of narcissistic self-loathing, see in myself: that neither of us had anything real obstructing the will to write. That there is no compelling reason to write except for love of writing: The money is bad, the moments of recognition come slowly and rarely, and neither are ever enough to live on. If their lack will destroy you, then you’re meant for something else. Nobody will hold their breath or a gun to your head for your sentences. And if the thing you wrote won’t sell, then all there is to do is write another.

Writing is hard, yes. But if you want it, you want it.

Writing is like any other job: There are good days and bad days, days when it comes easy, days when it comes hard, and days when it doesn’t come at all. But when I think writing is hard, I always remember Toni Morrison, who got up at four a.m. to write The Bluest Eye when she had two children, no husband, and a full-time job as an editor at Random House. If I’m honest, I remember myself, too: the days when I’ve written even though I was too morning-sick to get off the couch; the first novel I wrote even though I also had a full-time job; this very morning, as I write this essay on my phone while my son plays at the indoor park, because they have internet here and I know he can’t run away without my seeing him first.

Getting steamed and talking through my pancakes, I said to Meera what I’d been growing the courage to admit to myself through all these years of not selling another book. “You know,” I said, “the thing is—not everyone gets a lucky break. And I can live with myself if I don’t. I can live through that and still look myself in the face. But I can’t live with myself if I don’t do the hard work. I can’t live with myself if I don’t love the craft, if I don’t show up with a whole heart to my own dreams.”

And as soon as I said it, I realized it was true.

*

Laura Goode will teach an online workshop at Catapult this spring: How to Pitch Anything