On Writing Debut

Magic and Echoes: How Music Helps Me Write

Acoustic-rich spaces feel enlivening and the echoes they produce sound like life.

For a long time, I would listen to Arthur Russell’s “ Being It ” before I began writing. This was a practice, a sort of meditation, but it was one based on straightforward logic: If I listened to something I found extremely beautiful it would, I hoped, ease me into the sort of space in which making something beautiful was possible. The song would serve as a focusing object, a gentle and generative nudge— here it is, the kind of thing you want to make, remember? In this way it would function like a souvenir or a lucky charm—a pebble you plucked off a beach and kept in your pocket to rub.

I’ve since made peace with knowing that no sentence I ever write will sound as full of integrity as Arthur Russell’s ingenuous voice, the rough and sonorous churn of cello beneath it, and the echoey, fricative click of the tape being turned over halfway through the track. I’ve also realized, though, that the song is talismanic for reasons other than itself. No piece of art is impermeable or hermetic. As soon as it’s experienced, it becomes something else, colored by the listener and, in time, sedimented with emotion and memory. The resonance of “Being It” comes not just from the literal, sonic reverberation of Russell’s world of echo (a phrase which is also the name of the 1986 album that includes the track), but from my own world and its echoes. It’s the memory of watching Matt Wolf’s acutely moving documentary, Wild Combination, in London almost a decade ago, and how this film—and by extension Russell himself—were introduced to me by someone I loved. How the sense of that person and subsequent others are now refracted by the sound of Russell’s music. How they make sense of it for me and it makes sense of them: the silent, ongoing conversation of this.

Russell died from AIDS in 1992 at the age of forty. He’d recorded World of Echo before his diagnosis. If I’m in the city on the 21st of May, his birthday, I’ll go to Gem Spa on St. Mark’s Place and Second Avenue and drink an egg cream in his honor. The drink itself—an echt and revolting concoction of seltzer, chocolate syrup and milk, so unfashionable as to be almost a relic by this point—is not what I thirst for. What I’m drinking down is a sense of communion.

The song, then, is bigger than its five minutes and twenty-three seconds of sound. It’s a vessel for decades and their worlds and this is what I want for every sentence: a world of echo. That to me seems like writing doing its job: when it’s saying more than it says, and it’s generous with invitation toward other worlds, both its own and the reader’s.

I think of the fact that a soundproofed room, in other words, a room with no echo, devoid of acoustics, is described as “dead.” This is a technical rather than poetic term. Technics and poetics, however, are not always separable. To step into a sound booth is to feel deadened and airless, as though depression has been made external and atmospheric. As any kid who’s ever shouted into a canyon or cathedral knows, the opposite is also true. Acoustic-rich spaces feel enlivening and the echoes they produce sound like life.

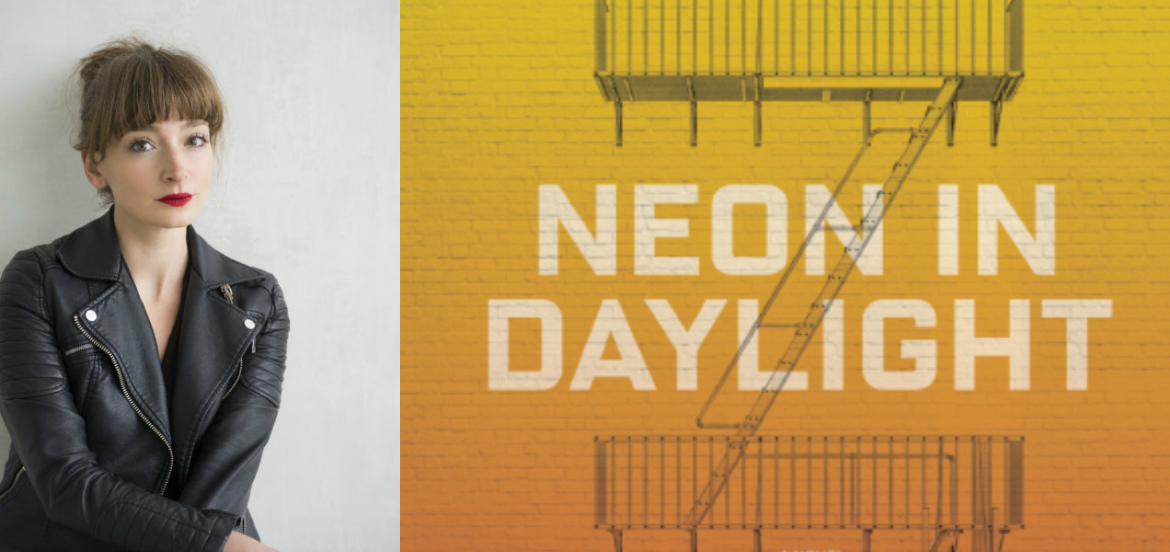

That’s one way, then, to write to music. And then there’s the other way: the functional, craft-based mode in which music is a plain tool, something to be, well, instrumentalized to the task at hand. I said I wanted every sentence to be a world of echo, which isn’t quite true. Sometimes you need a plain, flat-footed thing of a sentence: a hard surface for the surrounding phrases to bounce off. And sometimes, things really do just need to be purely functional. I wrote my first novel, Neon in Daylight, to the music of three old dudes: Steve Reich, William Basinski, and Philip Glass, a trio of New Yorkers, in rotation, to propel me through a novel in and about New York. I ended up listening to them not for their affinity with the city, but for their sound. All of them make wordless, propulsive, absorbing music, forceful enough to be galvanizing, mellow enough to recede when needed. Music, then, which served my purpose. Again, though, the practical and the romantic don’t exist in entirely separate worlds.

I liked to remind myself, for example, that Glass was a New York city cab driver for years; it’s always seemed to me a jewel of a biographical fact. When I wrote to 1982’s Glassworks, then, I was doing something more than the sonic equivalent of Adderall. Yes, it got my brain ticking and my fingers typing, but didn’t all those rushing arpeggios, for example, feel a lot like a crowd of pedestrians surging into movement at a street crossing? Didn’t those rhythms have something to say about the crosscurrents of Manhattan traffic, the wide streets, and arterial flood of yellow cabs? Wasn’t it true, then, that I was finding my own music for Manhattan, out of Glass’s?

I did the same with Basinski. Sonically, there is something peristaltic about “The Disintegration Loops”: It contracts, pushes, contracts again like some mighty organism. This is how grief moves too—the pain of contraction and release. The piece was made in the summer of 2001 when Basinski came across an old tupperware box of tape loops that he’d made almost a decade earlier. As he set about transferring them to CD he realized that the tapes themselves were physically disintegrating, their iron oxide particles turning to ashes, leaving moments of silence in the new recording. As he put it: “the music had turned to dust and was scattered along the tape path in little piles and clumps. Yet the essence and memory of the life and death of this music had been saved: recorded to a new media, remembered.” Weeks later, the planes hit the World Trade Center and “The Disintegration Loops” sounded both prophetic and elegiac. In 2012, I asked Basinski if he was susceptible to the notion of music having some greater power. “Well I think music does,” he says. “It resonates, you know?—It just goes on forever, and I think certain kinds of music can change the resonant frequencies.” As objects, the tapes that made the piece are dead, literally speaking: disintegrated. And yet, transubstantiated into “The Disintegration Loops” they go on forever, a world of echo.

I’d listen to them when I needed to slow down in my thinking and tune back in to some undertow. It was intense, a listening experience like sitting alone in a room of Rothkos, that same gravitational pull. No one can make a whole novel of Rothkos. It was Steve Reich’s Music for Eighteen Musicians then, that sustained my writing the most. I wrote mainly in cafés and if I had a particularly good session, I’d go back to the same place the next day, at the same time, to find the same seat, and hope to plug back into the same groove, or seam of good luck, or whatever the right word is for that fizzing surety when writing is going well. Maybe the only right word is “magic,” and magic, invariably, wears out. Which is why working in cafés necessitates a sort of crop rotation. The richness fades and dies, and then it’s time to find a new spot and mentally designate the previous favorite a fallow field for a few months.

Sound, however, has a more durable magic. I must have listened to Music For Eighteen Musicians more than any other piece of music and it still has a Pavlovian power for me. I plug myself into headphones and with the first staccato notes—propulsive and energized, but most of all, highly familiar—I’m ready to write. Why hasn’t the magic faded? Maybe because the piece is not, despite its title, really music. Or at least not in the most conventional, classical sense of a composition of phrases, movements, resolution. Instead it’s more of an exercise; a communal construction; some radiant machine made of its human moving parts, architectural and buoyant; a piece built on repetitions, which is another way of saying echoes.

In May of 2015, I was in the bathroom of divey bar where, in that dumb and unthinking, compulsive way, I checked my email. My prospective agent had written me a long, fortifying, generous email about my mess of a manuscript. I read this astonishing email several times over, rapt with gratitude and disbelief, knowing it was more than I deserved, and privately noting that her email seemed to me a greater piece of literature than the putative book she was cheerleading. And then there was a PS, a two-line afterthought of a second email: Did I, by any chance, and why was she even asking this, but did I write this while listening to Philip Glass? She doubted it, but, she wrote, “I have that uncanny association.”

I looked down at my arm to see the bloom of gooseflesh. I stayed there, in that scuzzy toilet stall for some time, rereading the email and its PS. When I emerged after a significant number of minutes, I was wide-eyed and fiery. (Looking back on this, I suppose friends must have assumed I’d been in there doing lines, rather than, well, reading them.) There was nothing in the manuscript to indicate Philip Glass, but she’d caught the echo of it and this “uncanny association” seemed an even more resonant factor than the sound encouragement of her long email. I put my trust in the uncanny association, and you could call this foolish superstition, but I think of it in another way: I remain susceptible to echoes, to the things and the people that are full of them.