How To Resist

In Praise of the Salon: Field Notes for the Aspiring Bluestocking

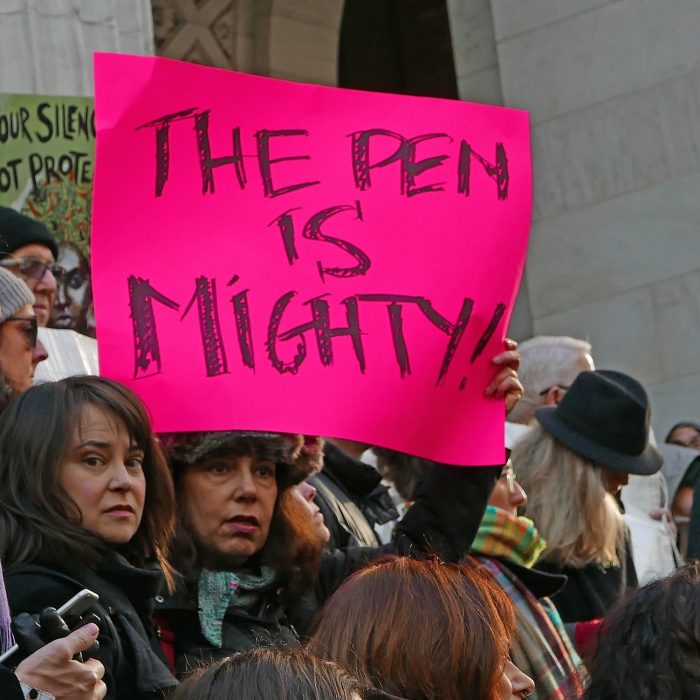

I witnessed how easily art might braid to politics, how easily fellowship might inspire movement.

Our teacups have been replaced with tin mugs of wine. Several copies of Imbolo Mbue’s Behold the Dreamers gaze up from the coffee table — but no one disturbs them. Instead, above the books, someone stabs the air with a rallying cry. “But how to act, ” she is screaming. The stressed verb is repeated, puzzled over; soon, concrete suggestions start to spin out like webs. The conversation proceeds at a fever pitch, but people cede space when it’s needed. We listen before we respond.

It is November 12, 2016, and our book club has been overthrown.

In a beautiful living room in Ditmas Park, I behold the dreamers of my own acquaintance — livid ladies all, crying “Revolution!” without a shred of irony. And I do that dreamy writer-head thing and for an instant, see our humble collective as Emma Goldman and friends, fomenting dissent in some back room of a Lower East Side tenement washed with smoke. I see us in pompadours with pursed lips and corsets, femme-tastic constituents of the salons in Enlightenment-era France (see also: Benjamin Franklin’s Junto; see also: the Algonquin Round Table; see also: the moveable feast of Gertrude Stein; see also: the Saturday Nighters of Washington). Discourse in these dire days, among underdogs and artists, might seem romantic, indulgent even — but there’s a more practical and immediate argument for the salon. These rooms of history were associated with movements.

As my former book club begins to draft a manifesto, I feel—for the first time since Election Night—a lick of hope. Yes, I hear myself say, thumping some nearby object (it is a lamp). Yes, we will act, we will revolt, because look at us yelling, look at us in this room, toe to toe and eye to eye, oh aren’t we a mighty We indeed!

Once I get home, I go online to read more about how to stay woke in a country that’s done lost its mind. Then I venture to Facebook, where I skim mini-thinkpieces from my brilliant friends and vague screeds from some untraceable acquaintances. The ruptured country, from this distance, looks quiet and sterile in comparison to the room I’ve just come from. I go to sleep more diffuse, somehow. And I dream of those smoke-filled, noisy rooms.

*

You don’t need to hear the hipster/grandma/prepper’s ideological rail against technology, how it is ruining our ability to Only Connect, for I see you and you see me on this 6 train, our eyes attached to our portals. Still, I’m considering the difference between the way discourse is conducted in-person versus on screens in these particular, troubled times, when listening seems crucial and grouping feels safe. What remains so seductive (heck, pro ductive) about the full, frenetic living room, the many wide-eyed humans shouting together?

The Hôtel de Rambouillet salon in seventeenth-century France — widely acknowledged to be the first of its kind — is credited with establishing French as the language of diplomacy, among other political and sociocultural contributions. While some considered the women of “the Rambouillet set” to be precocious (it should be noted that the salon has always been subject to sneerage; she is historically a bourgie institution) Madame de Sévigné, the company’s founding member, took pains to distinguish her room from an Academy. She declared that her salon would offer “divertissement as well as enlightenment.” And according to Frances Mossiker’s biography of the great lady, communication at l’Hôtel “was not by lecture but by conversation — always sprightly, however scholarly.”

This marriage of sprightliness and scholarliness, the casual and the cerebral, is a useful entry point for today’s aspiring bluestocking. The tone certainly worked magic on the event formerly known as my book club. I remember one Ditmas Park dreamer saying, in the thick of our communion, that she planned to join a self-defense class to prepare for the new regime, which snowballed into a group desire to take up kickboxing. We were serious as anything, the impulse was serious as anything , yet I recall laughter; excitement inside the rage. It was the kind of suggestion that could only be uttered in a very specific group, and in a very specific mood. The kind of pledge that will only ever be fulfilled if we meet again.

The women of l’Hôtel de Rambouillet were encouraged to learn from one another in lieu of installed authority figures, and they did just that. They made waves in a society in which it was harder for women to do so, and they did it by embracing a range of topics, a range of tones.

*

Post-Enlightenment, the definition of the salon expanded. Into the nineteenth century, the term no longer applied only to the rich intelligentsia with idle time and a spare parlor or four. What remained the same was the spirit of the gathering, with its emphasis on conversation. Even as the parlor morphed into the grungy attic or assembly hall, a faith in the use of coming together to converse in tones heady and light prevailed — and so too did a desire to braid art and politics.

The Bloomsbury Group never defined itself as a salon, yet this set of artists championed many progressive political ideas at their gatherings: gay rights, free love, and pacifism among them. Ruth Logan Roberts, a suffragist and civil rights activist, hosted a salon in Harlem for community leaders and artists alike. And the New York Women’s Literary Salon saw feminists and art-makers Judy Chicago, Kate Millett, and Adrienne Rich rubbing elbows.

Such groupings were born in historical moments that required political engagement from their artists; moments when the world felt so unjust that the need to shout about it was strong. There is some revolutionary spirit inherent to the smoky room, with its loudly plotting members. If political turmoil is the crucial impetus, art is one conclusive action the salon, the conversation, can produce.

Dena Goodman argues in The Republic of Letters (her arch-text on the Enlightenment) that the very fact of spirited conversation proved crucial to the Enlightenment itself; there’s no way to divorce the capsule of the room from the ideas it spawned. This seems to be a truth, still, as artists continue to seek enlightenment in a culture that sometimes resists progress.

*

I still want to pinpoint the specific magic of the room that night. Because it wasn’t just the books on the table, the tin cups or the wine in them. I look to philosophy: Emmanuel Levinas, the OG ethicist who no doubt attended a salon or two in his day, argues that it is the encounter with the face of the Other that enables productive discourse of any kind. “The metaphysical desire for the absolutely other which animates intellectualism . . . deploys its energy in the vision of the face,” he writes, in Totality and Infinity. “The Other remains infinitely transcendent, infinitely foreign . . . [and] Speech proceeds from absolute difference.” The very word “movement” feels connected to the salon — for to engage in Levinas’s idea of true “Speech,” to admit the Other, is to enable some movement in oneself. We can move and shake, it would seem, only once we have moved, are shaken.

I was recently part of a workshop with salon potential that self-destructed. We never quite nailed that balancing act between the spritely yet scholarly form and content, for one thing. But the ultimately immolating smoke-bombs were hurled via email. We did not once talk in a room while an argument spiraled past healing, and most of us haven’t spoken in person since.

They say you can’t hate a person if you know them. Well, I raise you: Can you know a person if you don’t make a point to see their face? If you dare to disagree up close (let alone take action about this disagreement), at least there’s this much to contend with: Tone. Eyes. (Tea. Whisky.)

Over the years I’ve been part of many writing workshops and book clubs. I have gone to readings and meetings and protests. I’ve stayed late in bars and on rooftops talking Deep with strangers and friends, I have Epiphanied on the street outside of theaters, I have clutched the hands of acquaintances while watching the world onstage, on TV.

But the ideal smoky room in my imagination, the hectic globe of talk toward action, has the same criteria that make Rambouillet like the Lower East Side like Bloomsbury. For to be a salon, I think, the room and its constituents must embrace the most useful contradictions in human experience: the “divertissement” and the “enlightenment.” The “political” and the “aesthetic.” The “Other” and the “Self.” Mine is a room for swishing snifters and knowing fellowship, but it is also a room for cross-pollination and serious strategizing. It is a room small enough to hear your neighbor, but large enough to fill with ideas. It is a room for talking loud, but listening hard, too. A room for feeling safe and being brave.

I note the difference between thought and action, dreamers and dreams. But of one thing I remain sure: In the aspiring salons I’ve known, I’ve felt both momentum and empathy in my heart, whereas alone in my living room before a computer I have too often felt the most useless rage, a rage that often kowtows to convenience.

*

On November 10th, I met with a group of fellow playwrights. We were supposed to be having our weekly workshop, but instead about twenty of us sat in an empty theater and said nothing for long, painful minutes. There was nothing to say, precisely, but some magic held us there; maybe that Hallmarkian love they say trumps hate. Our super-sad-true party was interrupted by a tardy group member who burst in flush from a protest and described marching to Trump Tower with the hurting masses as “the only thing that has made me feel like a person again.” Her words broke some spell, and the room caught fire; we began to stab the air with rallying cries. Some of us just needed to rant, or cry. Some of us needed to question our commitment to art, which suddenly felt trivial, in need of new context.

But the conversation spiraled, finally, toward action: One of our leaders suggested that our group seek out connections with regional theaters in the Southern states in attempt to find more common ground with that redder America. Someone else suggested that we dedicate our recurring short play series to a different cause each month, and challenge ourselves to write plays with a political bent while our tip jar proceeds go to organizations like Planned Parenthood, or the Muslim Advocates. The world was not remade, but it did begin to feel a little closer. And I witnessed how easily art might braid to politics, how easily fellowship might inspire movement.

We writers talked, mostly of action, the rest of the night long. And every weekly meeting since, we’ve left space for fomenting. We’ve made plans to march together. We’ve organized drives for charities we care about. We discuss the art we’ve seen, as always; and sometimes we argue, though we also attempt to understand. We laugh and drink. We write angry angry plays and read them in a room altogether, aiming to put our strongest art on the world we don’t presently accept. And I believe we — mighty We! — tend some fire.