Fiction Short Story

Room 105 at the Ramada on Sundays

Mary decided then and there that Harold would do. She missed skin on skin. She missed letting go.

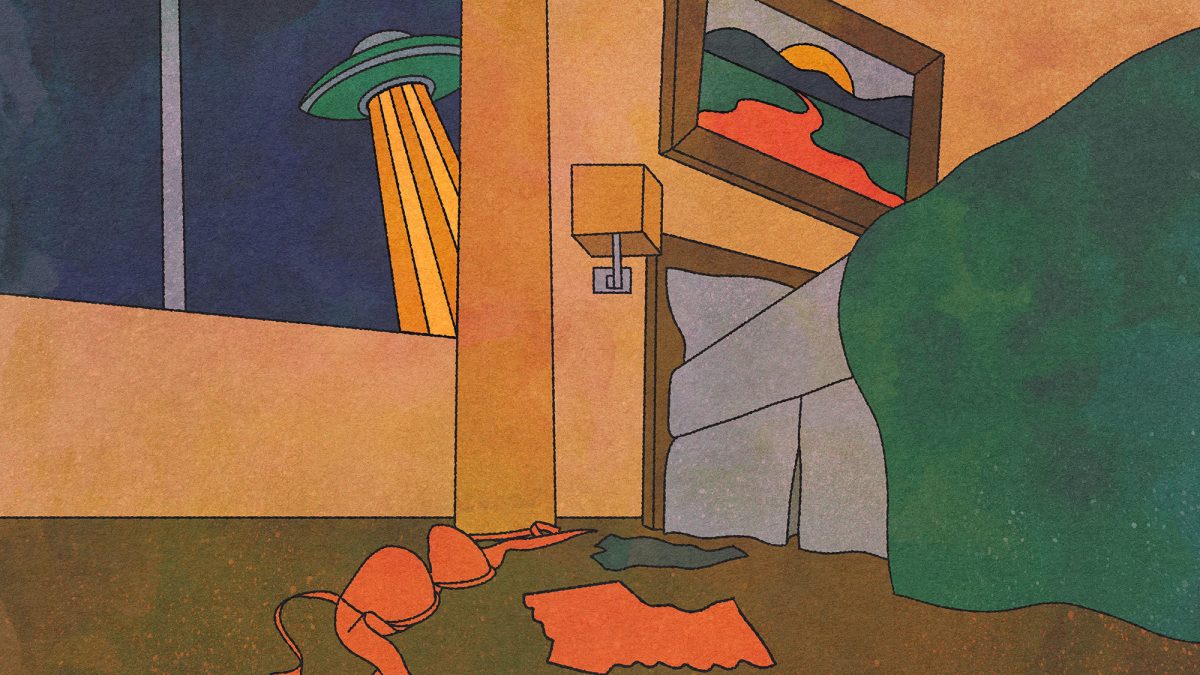

The Ramada off Highway 99 had good sheets: clean, a nice cornflower blue. Harold didn’t care about things like that—a hotel was a hotel to him, just as a rifle was a rifle and a walnut was a walnut. Everything was only its most simple definition for Harold, no seams for nuance to sneak in. But for Mary the details mattered. She’d made a career out of paying attention to the length of a sleeve and the diameter of a sequin. Some might call selling wedding dresses a job, but she loved what she did and she’d do it until she died. Commitment makes a career, and commitment was what Mary was after in most things.

Except Harold. He was her midlife surprise, her Sunday special, her fucking man of the hour. Harold didn’t like to say the word, he was old-fashioned that way, but with Harold, it was definitely fucking. Not making love or having sex like it had been with her late husband—sweet, dumb John—or her first love, Bethany Brown, who was so scared of her own wiry pubic hair that she shut her eyes tight every time they “got intimate,” as she preferred Mary to say. With Harold, it was top-to-bottom fucking time. So Mary was surprised when he wanted to talk about the UFO.

“I need to tell someone. Gina wouldn’t understand,” he said as they lay naked on their backs on the Ramada’s good sheets, sweat pooling behind their knees. He’d never mentioned his wife before, but Mary knew her name among the few biographical highlights she’d gathered from Joanie at church. Mary considered these words from Harold, words that other women in her position might long for. But Harold was Mary’s fucking man. She wasn’t looking to be his soft shoulder.

“I’m with Gina,” Mary said. “Maybe keep it to yourself.” She imagined Harold’s wife to be smart and sturdy, maybe even relieved for a break from the worn-down grooves of a forever promise.

Harold shook his head on the limp pillow that had been wedged under Mary’s thighs five minutes before. “I can’t hold on to it alone anymore,” he said. “It’s eating me up like a husk fly on the fruit.” Mary never got his agricultural references. She was a city girl: shoes that clacked, tinted SPF, no need for nature to muss up what was put together just right.

“Well, get it out then I guess, Harold,” Mary said with a sigh. Talking was not in his tongue’s short list of talents. Months back in the pews, she’d noticed Harold’s wide, strong back funneling into a neat waist, a geometric elegance rare for any man, but especially one his age. She’d decided then that he’d do. She missed skin on skin. She missed letting go.

“I think I killed them. No, I did kill them,” he corrected in his Harold way, changing a maybe into a for sure. Mary kept looking up, watching the brass chain on the ceiling fan tick-tock in the breeze. Let him get to the end , she thought to herself. Everyone has their stories. Joanie had said Harold had been in the navy, and Mary wasn’t one to presume she knew what life was like on a boat built for war.

“Alright,” she allowed. “Say what you need to say.”

“I shot down their ship. I watched it crash. I waited an hour to see if anyone came out.” Harold moved his sunburned fingers over Mary’s hair, stroking the strands of her box-dyed blonde. He’d never been so tender before.

“What ship?” Mary asked. “Who’s ‘they’?” She wondered how much longer she’d need to lie there. She had laundry to do, a whole chicken to pick up for the girls’ dinner. She didn’t have time to debate if her suddenly chatty Sunday man was a regretful criminal or long-ago pawn.

“A flying saucer,” he said, “filled with little green men, like in the papers at the checkout. I shot them right out of the sky, and now it’s making me sick. I feel just terrible.”

Oh , Mary thought. She decided this would be the last round at the Ramada. Too much trouble even for a high-quality fuck, even after all this time. “I’m sorry, Harold, I am,” she said. “But why are you telling me ?”

“Well, you’re a sinner too,” he said to Mary. “How do you manage your conscience after committing adultery on the Lord’s day each week?”

Mary sat up and looked down on Harold’s bare body on the bed, his shriveled skin free in the afternoon air. He didn’t mean to offend, she could see. He truly wanted to know how she could sit across from her children after getting the snot blown out of her by a married man. He really believed that the pleasure Mary had found in Harold’s open arms should drive her to shame, guilt equal to Harold’s suffering—even if the lives he mourned were likely just ghosts of shell shock, dementia, one beer on a dark porch too many. A sin was a sin to Harold. But had he forgotten that the blue sheets were stained with his sweat too?

A sin was a sin to Harold. But had he forgotten that the blue sheets were stained with his sweat too? A silent Mary dressed again in her favorite summer dress with the flowers and white buttons, and she splashed water from the bathroom sink onto her face, under her arms, between her legs where Harold had dined before telling her she was going to hell. There was still time for the chicken, maybe even enough to get the girls something extra for dessert. The three of them loved to eat strawberry ice cream out of the container sprawled out on the kitchen’s crisp linoleum floor, Mary’s littlest letting the liquid sugar dribble from both sides of her mouth like extra pink teeth. She was only two when John’s car crumpled like a cheap tin can; she needed all the sweetness she could get.

Harold didn’t protest when Mary walked out of the hotel room for the last time. She left the door wide open—some “space for the Holy Ghost,” as her Sunday school teacher used to hiss when she and Bethany Brown got too close. Or maybe today, she figured, a seam for all the souls of the little green men whose adventures Harold had cut short with his one blunt instrument.