Excerpts

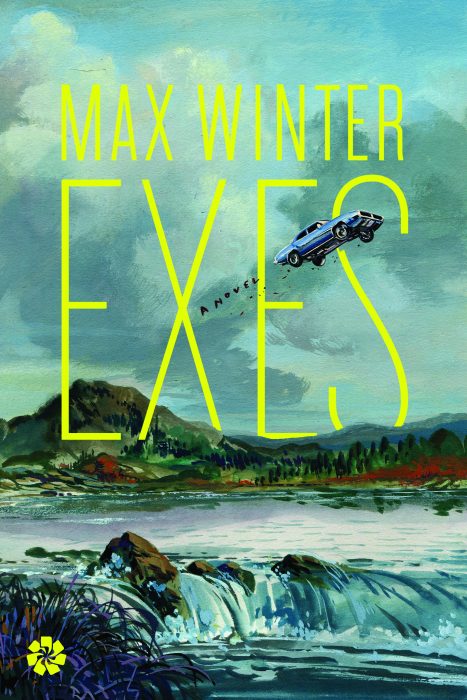

“Every story is a ghost story”: An Interview with Max Winter, Author of EXES

“Human time is neither straight nor shapeless; it is instead like coral: whorled, fragile, and, in the end, ordered. And made out of skeletons.”

Matt Sumell interviews his longtime friend Max Winter, author of Exes: A Novel (out now from Catapult!), and the two discuss everything from H.P. Lovecraft’s tombstone to successfully writing semi-autobiographical fiction. Their podcast is launching soon (or rather, it should be).

Matt Sumell: Did it really take you fifteen years to write Exes ?

Max Winter: Yeah. I had been saying ten, in part because it’s a nice round number, but also because it sounds less sad, more familiar. Then I realized I had been saying ten years for at least five years, and I really didn’t want to start this whole thing off by lying. Because the self-exposure and explication that book promotion demands may very well be weird and gross, but we didn’t go into this insane non-business to avoid telling the truth. So, yeah, fifteen years.

My problem with lying is that I suck at it and get caught every time.

That’s true. You are a horrible liar. My wife is the only adult I know who’s worse.

Each of these chapters and the sentences themselves — are devastating not just in your rendering of hearts sorting through their own broken pieces, but also, they’re so FUNNY . I’m astounded by how sad you can make me while cracking me the fuck up. I mean, when Cliff Hinson is confronted by that security guard and we get:

“Who are you and why are you here?” “I’m a ghost,” I said, thinking about it. “And I’m a ghost.”

COME ON! Can you talk a little about that relationship between the humor and heartwreck? It seems like such a balancing act and frankly, well, I’m envious.

You’re envious? Of me? You, the same guy who once described someone as “[walking] off, fatly?” Or had his main character “punch a guy’s hamburger”? Or who wrote the otherwise Google-proof sentence (I’m guessing—won’t verify, for obvious reasons): “Yo, [Mom’s] vagina is in a lot better shape than I thought it’d be”? Is this one of those self-flattering, but-enough-about-me-what-do-you-think-of-me-type set-up questions? Dick.

Ha! I’m kidding! Because we both know you’re not that kind of dick, so this can only mean that you somehow genuinely don’t realize that it was you who showed me that it’s okay to put jokes in sad stories. Which surprises me, but also thrills me because now I can tell you so publicly.

So, yeah, no . . . You, all right! I learned it by watching you.

One of the things I find so impressive about your work is your ability to inhabit others; that this book is narrated by nine different people, with nine different voices, including two women. As someone whose entire book is narrated by the sweethearted but dickheaded Alby, I’m curious about the difficulties of that.

Well, I’ve always envied you your ability to fictionalize, successfully, your own perspective. Yours is the rare even remotely semi-autobiographical fiction that manages to be immersive and voice-driven, while also maintaining a real, distinct authorial point of view. Alby reminds me of Junot Diaz’s Yunior in this and other regards. There’s a brainy and navigable space between the two planes. Which is amazing and maybe even psychologically impossible.

My work, meanwhile, is more like dissociative personality disorder. But I just embrace these multiplicities, because whenever I write about anyone fundamentally and/or superficially like myself, almost nothing happens. There’s just this dumb, ineffectual witness on the page—one burdened with predictable, intrusive, and, ultimately, story-destroying preconceptions. It sucks. So at most, I’ll maybe exaggerate my best and worst qualities and/or experiences to the point where they cease to be identifiably my own, even to me. But mostly I just invent characters out of whole cloth, or else out of stitched-together bits and pieces of some people I never knew well enough, or else much too well. I spent most of my childhood gauging other people’s reactions to one another, imagining how and why they might crack up or blow their tops. It was the seventies, so I had a lot of different babysitters of varying degrees of competence; and a good number of my parents’ closest friends faced timeless but also period-correct struggles of one sort or another. I’d get dragged to parties and read Zap Comix and happily eavesdrop while the adults drank jug wine and told funny, hair-raising stories.

As for writing women characters, well . . . I don’t know. I mean, look, I’m a straight, white dude, and can’t and shouldn’t pretend not to be. But, even so, writing from certain women’s perspectives has always felt natural for me. Maybe because I grew up in a matriarchal home, and went to what had been, up until very recently, an all-girls’ school. And even now, I tend to feel more comfortable around women than I do around men.

I can’t talk to you about Exes and not talk to you about place, because it’s such a huge part of the book. I once went on this double-decker bus tour out here in LA, an after-hours thing where this comedian gave a personal tour of her LA; like, I once gave a blowjob in that alley, and this is my ex-boyfriend’s apartment, fuck him, and so on. I’m not doing it justice of course, but it was brilliant, and I’m reminded of that brilliance because the Providence that I know is unlike the one you depict, the Providence of the 1990s, which seems dirtier and more menacing and much more interesting. Can you talk about that?

I apologize in advance for what will probably be an overlong non-answer to your question, but let me start with the problematic matter of Providence’s H.P. Lovecraft, and of the insane phrase carved on his tombstone: “I AM PROVIDENCE.”

It’s from a letter, which makes sense, as it both does and does not sound like Lovecraft , Our Greatest Bad Writer and a horribly shitty human being. I don’t care if he was nuts and that so were the times: about certain things, a writer should know better.

But it’s worth putting the quote into context, something which—unsurprisingly—does Lovecraft few favors:

To all intents and purposes I am more naturally isolated from mankind than Nathaniel Hawthorne himself, who dwelt alone in the midst of crowds . . . The people of a place matter absolutely nothing to me except as components of the general landscape and scenery…. My life lies not in among people but among scenes —my local affections are not personal, but topographical and architectural…. It is New England I must have —in some form or other. Providence is part of me—I am Providence . . .

So this fucking guy—the one who not only hates people who are different than him, but also people in general—is our fucking local literary hero. Great . . . Just great. A racist, a sexist, a xenophobe, a misanthrope, and a solipsist, which is pretty much the Venn diagram of all that’s wrong with the world, minus greed. (Oh, and if you’re keeping score at home, he was also an anti-Semite. Wait… Bingo!) And Lovecraft haunts my book every bit as much as he does my hometown, a place with which I also clearly have a pretty complicated relationship.

When my diamond-minded grandma, Selma, applied to Brown—or more accurately to Pembroke, their women’s college—she was rejected because they had already reached that year’s quota on Jews, so instead she went to Syracuse, where she became a Communist. Sixty years later, I would apply for a custodial job at the same institution. My college degree confused them, so I said I wanted to write, which I did, but that hardly helped, not that it should’ve, and they didn’t hire me. Oh well , I thought, as I often did in those days.

I had just moved back from New York City for the third and final time. I also didn’t get the record store job either, and maybe because my then-girlfriend’s ex wasn’t sure he could work with me, but I never blamed him and we later became friends, which is just another example of how and why I say Oh well . Point being, my greatest strength isn’t always that. (And further evidence, if any were needed, of why I don’t write autobiographical fiction.)

That’s why I always make Alby have the worst possible response to whatever’s going on. It keeps the story moving. Bad choices make for good stories.

Right! But thing is, my girlfriend’s car, which I had borrowed, got towed during the interview at Brown. It was snowing pretty hard that morning, and I didn’t want to be late, so I hadn’t seen where the townhouse up the street’s driveway started. Plus the car, bought used in the Southwest, had windows tinted dark enough to warrant its being pulled over in wealthy neighborhoods. It also had a crack in the dash where my girlfriend had kicked it when I told her I wasn’t American, I was Jewish. But, then, I hadn’t done a very good job of explaining myself—something that’s never come all that easy, if I’m being honest. I’ll take the long way around, miss exits, inadvertently cut people off, get everybody lost. I owe her and many others apologies for all kinds of things.

We could easily replace our Acknowledgements sections with Apologies sections. We wouldn’t even have to change any of the names.

Uggh. I know . . .

Anyway, my grandma Selma only visited us in Providence once, maybe twice—the town her daughter, my mother, believed to be part of Long Island up until her acceptance into its renowned art school—a choice which hasn’t confused me for a long time.

Even so, I only feel worse and worse about having not put the following in my book’s acknowledgements section or wherever:

Exes is a work of fiction, so please don’t mistake its Providence with the real-life city which inspired it, nor its inhabitants with their far kinder, saner, non-fictional counterparts.

Or something to that effect. You get the idea. Or maybe you don’t? Point being, it’s neither a portrait—group or otherwise—nor a map. It’s about portraiture, of course, about mapping, but it is only concerned with capturing what isn’t there. But even then only in terms of how certain individual minds perceive of these absences, and where they locate them, because, ash-casting notwithstanding—and even then!—the whole idea of the grave is based on the idea of the dead needing addresses.

Michelle Latiolais liked to talk about how cities exist in many different times at the same time.

And it’s especially true of Providence. In its repurposed customhouse you can glimpse the remnants of its shameful past (we oughtn’t forget that the word plantation is literally in its trivia answer of a full name); in its former textile mills either renovated or razed, the at turns precious and nervous sell-short present; and in the under-booked expo center’s seemingly needlessly close-set electrical outlets and proximity to the Peter Pan depot, bitter whispers of a loose-slotted, go-for-broke near future. Because in cities like Providence, there’s never just one point in time, and for me, at least, that’s the whole point. History cannot accurately be charted by Euclidean means. Only hyperbolic geometry will do its simultaneity and its constant doubling back justice. For human time is neither straight nor shapeless; it is instead like coral: whorled, fragile, and, in the end, ordered. And made out of skeletons. Every story is a ghost story, just as every story is a mystery. All fiction is historical fiction and horror is not a genre.

So, in many ways, Exes is a eulogy for a Providence that never existed anywhere but in Clay Blackall’s head—a head just about filled with pulpy tales and gruesome juvenilia and misremembered and/or misinterpreted bits of pop culture, local lore, and assorted torts and grievances. “Adulthood is hell,” as Lovecraft once remarked, and for mostly different reasons, Blackall agrees. But he is not Providence, and they are not Providence, and I am not Providence, and this is not Providence—for Christ’s sake, no one is.

What’s wrong with us?

Jesus. A lot. Plus, the things we’re good at, the world tends not to reward. Because our “skills”—stubbornness, hypersensitivity, rewriting the same fucking sentence over and over until it’s perfect! I mean, wait, no, that’s still not right—aren’t exactly indicators of mental health. People have written books designed to cure people of that which enabled us to write ours, and theirs will always sell better.

Well, as a fellow sufferer I’m just glad you ended up in my ward, and I’m grateful they haven’t cured hypersensitive-enlarged-hearted-fuckup-itis yet. You wrote a really great book , man. Congrats on it.