Arts & Culture Rekindle

Get Down to Work or God Help You: Reading Etty Hillesum

When Etty wrote to herself, I heard her speaking to me, and I took her words to heart.

I would like to forget the ways I was sick in the fall of 2010. What I recall most clearly is being exhausted and lying in bed in an all-white room in San Francisco—SoMa, specifically. I was sick with endometriosis, anemia, and allergies that kept turning into sinusitis. Also sciatic and intense lower back pain that made it difficult to stand or walk many blocks. I lived with my mom and her partner; they paid the rent and filled the fridge with groceries. A few days a week, I worked an unpaid internship for a non-profit in the Presidio. Once or twice a month, I went to massage therapy, trying to get a little relief and spending down the few hundred dollars I still had saved.

When I wasn’t in the Presidio interning, I passed a lot of time in bed, horizontal, reading essays on The Rumpus or playing Bubble Spinner, an online game that involves popping bubbles with increasing difficulty. Outside the warehouse where we lived was the recession, into which I’d graduated almost a year before. It was difficult to find a job even for highly qualified professionals, much less new grad Psych majors who couldn’t seem to get out of bed for more than a few days at a time. Most annoying of my symptoms were the allergies; at night I dreamt of pulling out whatever mucus was stuck inside me. The endometriosis was particularly out of control that fall, leading to breakthrough bleeding and pelvic pain for up to ten days in a row. This ranged from low-grade cramping to spasms that felt like my uterus was an orange and someone was peeling it with a scalpel.

But what was most concerning was the exhaustion: I needed to spend so many waking hours lying down. And almost every time my body fully relaxed, it began bleeding, even though I was constantly on birth control pills. Like my body was just waiting to do this thing I spent so much effort trying to get it not to do. I had ambitions; I wanted to make enough money to live on my own, and have enough energy to go to birthday parties, concerts, yoga, dinner. I desperately wanted to be less confused. My body had other plans.

What I really wanted was to be a writer. Or rather, I wanted to write enough to call myself a writer. But I didn’t know what I had to say that could be of value to anyone else. And I didn’t know how a person like me—too anxious to execute my ideas, too exhausted to go to readings—would be able to put together a life that allowed me to write.

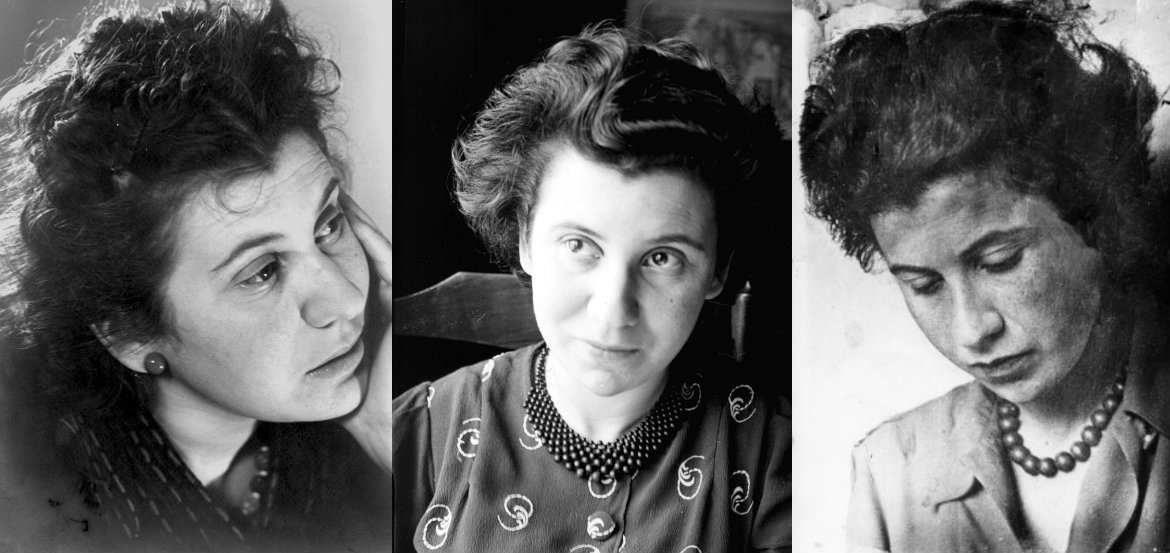

It was during this time that I found Etty Hillesum and her diaries. I wish I could remember where I came across the book; I’m fairly certain it was in a used bookstore and that I picked it up on a whim. Like Anne Frank, Etty was Jewish, writing a journal in Amsterdam during World War II. Etty, however, was in her late twenties. As the German occupation ramped up, she was experiencing a spiritual awakening. Etty was also ill on a regular basis, and working through her physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression to get herself to continue writing.

Her diaries are remarkable for their candor, her interior journey, and the time period in which she’s engaged in that kind of personal work, as her very existence and the existence of her entire community was being threatened with extinction.

Etty’s writing isn’t commonly included in the mainstream Holocaust canon, so to speak, for a variety of reasons. She was greatly inspired by Christian mystics and is sometimes claimed by Christians as one. The ways she loves and relates are radical, even by today’s standards. And, she eventually goes willingly to Auschwitz, believing her life’s purpose is partially to be “the thinking heart of these barracks” and to stay with her parents and brother as long as possible. During years of Hebrew and Sunday school, I don’t remember ever hearing her name. In New York last year, I went to the Grand Army Brooklyn Library to find a copy of her book and refresh my memory of her words. It had been seven years since I’d read it; my copy was in San Francisco, where I still live. Not only did they not have her book in that library, but they didn’t have it in any of the branches in Brooklyn. “Sometimes we stop stocking certain books. It looks like it was published in 1996,” the librarian told me, by way of explanation. But can you imagine a library in New York not having a copy of Anne Frank’s diaries? Or Night?

An Interrupted Life failed to find a publisher for decades while Etty’s friends held onto her diaries and letters. Etty is a complicated figure; as her journals progress, she looks more directly and unflinchingly at the suffering around her. “What is at stake is our impending destruction and annihilation,” she writes, but she also refuses to completely give up on joy, faith, and equanimity. She resists being Pollyannaish, but it can be painful to read the grace she affords Nazis shortly before being killed by them. “I hate nobody,” Etty states multiple times in different words, and reminds herself: “German soldiers suffer as well. There are no frontiers between suffering people, and we must pray for them all.” Later, she clarifies that “the absence of hatred in no way implies the absence of moral indignation.” And, it’s worth mentioning that once she’s relocated to Westerbork, a transit and detention camp between The Netherlands and the concentration camps in Poland, Etty’s focus in her letters is primarily on the realities for Jews in the camp—the hellishness, despair, and suffering she witnesses daily.

Etty’s story is of a woman who isn’t playing by the rules of the time, a story rooted in the mind, but also in the body and soul. With sexuality in particular, she investigates prescient topics, including power dynamics within sexual relationships between mentor and mentee, and the spiritual and emotional challenges of ethical non-monogamy. Etty sleeps with multiple men; Etty writes directly to God; Etty documents her frustration towards her parents. And Etty eventually has some agency in going to Westerbork, and then to Auschwitz. She knew full well what awaited her after the train ride to Poland—“We are being hunted to death all through Europe . . . ”—and yet refused her friends’ offers to hide her.

When she wrote to herself, I heard her speaking to me, loving and yet stern, and I took her words to heart:

“Come on, my girl, get down to work or God help you. And no more excuses either, no little headache here or a bit of nausea there, or I’m not feeling very well. That is absolutely out of the question. You’ve just got to work, and that’s that. No fantasies, no grandiose ideas, and no earth-shattering insights. Choosing a subject and finding the right words are much more important.”

*

Like Etty, I cannot talk about my writing without talking about the body. Around the same time I was reading her diaries, I was gifted a session with a healer who specialized in iridology. She inspected my eyes, specifically looking for specks in my irises that would indicate disease and injury in the body. Based on the placement of the specks, she told me she would know the location and type of the disease. Even still, this sounds absurd to me, and no studies have been able to confirm the usefulness of the modality. I told her nothing about my medical history, I just opened my eyes to her magnifying lens and chart.

As she peered into my eyes, she told me about my endometriosis, my low iron levels, even a knee injury that I’d forgotten about. (Skeptical, I was excited to prove her wrong, but when I rolled up my left pant leg, we both could see the gravel still embedded deep in my skin from a rough fall in high school.) At the end of the session, she told me she thought that with diet changes and the right herbs, I might find relief from many of the symptoms I’d been trying to simply accept for years. She was the first person I can remember telling me she thought it was possible I could feel significantly better.

After being so unwell for so long, potentially the most radical part of finding some healing was simply believing that I deserved to feel better, and acting from that belief. Soon after that conversation, I found an acupuncturist in San Francisco who specialized in reproductive illnesses. Her Yelp reviews were fantastic. She stuck me with tiny needles in my feet, hands, and face. She gave me terrible-tasting herbs that would shrink the tumors; I made the recommended diet changes, tried to stop eating foods that were making me sick, and showed up weekly for appointments. Against my Western doctor’s orders, I went off the birth control pills that had been keeping me “healthy” since I was fifteen. I began feeling better.

A similar belief formed in my relationship to writing the month I contacted the acupuncturist: I told myself I deserved to write. Or perhaps, Etty and other women I read that fall told themselves they deserved to write, and I believed them, and believed myself to be among them. In my journal from that November, I wrote: “I don’t have to worry about the ‘why’ of my writing right now—I just now have to write and that’s enough. After it’s over, then I can worry about the why and the for whom, but now . . . just worry about getting it all down on paper.” And I began writing stories and essays, which I revised and kept to myself. I began writing something longer, something that was quickly becoming book-length, regarding grief. My stories were about young women, loss, love that exists in absences and silences. My stories were about the body.

There’s an interesting phenomenon that happens in many immigrant families in the US: Whatever challenges the second and third generations are going through are often much less severe than what happened to the grandparents or parents. The horrors of the past are sometimes evoked to try to give these youngsters perspective as to the unimportance of their struggles. In my family, this has rarely been explicit, the past a place still too painful to speak out loud, but the knowledge I did have of what they went through lived inside of me, and functioned as an internal judgment system.

We almost never talked about the Holocaust out loud, but my most frequent dream as a child was that someone was chasing me, trying to kill me, and I, terrified, needed to hide. I see it in my journals from as young as age ten or eleven where I’m already ashamed, aware that whatever emotional or physical challenges I’m going through are nothing, that “I have no real problems.” No one needed to tell me this outright; it seemed obvious, and I carried it with me as a young adult. So, yes, you are quite sick and trying to find employment during the greatest economic recession in decades, but it’s still not the Holocaust. It’s not being poor in Queens just after WWII and having to teach yourself English at the library while painting houses. My first and second generation friends and I compare notes on this, trying to find the right balance between awareness of and gratitude for our vast opportunities, but also how to navigate the present challenges of our lives. What to do about the problems of now? How much risk is allowed? How much misery and pain does a person have to just accept in her life, knowing that she will likely never have to confront as much hardship as her Jewish grandparents did in Poland and Russia in the 1930s and ’40s, and as their children did in the US during the decades just after the war?

These were some of my questions at twenty-two. And while I would have already said I was a feminist, I was lacking a feminism that reconciled putting together a life as a creative woman who had physical limitations within a capitalist society. I was preoccupied with the immense privilege I had as a white American citizen with financially stable parents. I’m not sure if I’d ever heard the term “invisible disability” yet; if I had, I certainly hadn’t thought to apply it to myself. Estranged from Judaism as a religion and, to some extent, as a cultural heritage, I’d made few Jewish friends in high school or college. I had very little idea how to incorporate the reality of my body and my Jewishness into my feminism, and into my sense of self. The trauma in my family line directly passed down from the Holocaust, through genes and taught behavior, wasn’t something I thought about much yet. I took my problems very personally.

In retrospect, it’s easy to see how gendered my pain was. Endometriosis only happens to people with uteri, and chronic pain impacts more women than men, although women are also less likely to be properly treated for that pain. I’d been going to doctors complaining of stomach, back, neck, and jaw pain since I was three years old, on and off, with greater intensity starting in middle school. It took three years of pelvic pain for me to be diagnosed with endo (and that was considered fast); no one came up with a reasonable explanation for the muscular pain, or what to do about it, besides taking over-the-counter painkillers. In doctor’s offices, I’ve been met with disinterest, vague curiosity, and gaslighting. A couple of years ago, at an appointment specifically for my muscle pain, a doctor said to me, “What do you think you should do about it? I mean, you’ve been living with it for all these years, so you probably know more than me!” Then he chuckled. Having spoken to and read work by many women with chronic illnesses now, this is all so normal as to be boring. By my early twenties, I’d almost completely given up on doctors to help me, and was instead reconciling myself to be that sick for the rest of my life.

I fantasized about being well, and what I would create if I had more energy, more clarity of thinking, if the days didn’t slip away into just managing symptoms. “But let me impress just one thing upon you, sister,” Etty wrote. “Wash your hands of all attempts to embody those great, sweeping thoughts. The smallest, most fatuous little essay is worth more than the flood of grandiose ideas in which you like to wallow. Of course you must hold on to your forebodings and your intuitions. They are the sources upon which you draw, but be careful not to drown in them.” I understood that I needed to start, and not get lost in my imaginations of what I would make, if. Because if might never come.

I looked around and didn’t find women my age living in bodies constantly in pain, living in bodies that challenged them to work for money and for pleasure, but working nonetheless, and dedicating themselves to their art. Of course these women existed, but if I read their work I didn’t know what happened behind the scenes of their work, which was what Etty gave me:

“With all the suffering there is, you begin to feel ashamed of taking yourself and your moods so seriously. But you must continue to take yourself seriously, you must remain your own witness, marking well everything that happens in this world, never shutting your eyes to reality. You must come to grips with these terrible times and try to find answers to the many questions they pose. And perhaps the answers will help not only yourself but also others.”

In these words, I heard that I could take seriously my own life, my own griefs and hopes. And that amidst much worse, a Jewish woman only a few years older than me had taken herself seriously, and had found room for hope, and a deep relationship with God, and a hard-earned love for all people.

*

Now, I have the words of Esmé Wang, Amy Berkowitz, Porochista Khakpour, Lidia Yuknavitch, and Sonya Huber to keep me company. But at twenty-two, I dogeared the shit out of Etty’s book and let it ignite a feeling in me: a permissioning, an urgency, a responsibility and ability to respond. If you are being given this life—and sister, it is so unlikely that you have been given a life at all—then it is wonderful and appropriate to not just spend it trying to survive, but instead to do more, to say what you want to say, to make what you want to make in the world, to at least try to heal what hurts. To strive towards joy, and a love for people and the world, one that refuses to ignore the worst of what humans could do to one another. And yes, yours may be frivolous words, or maybe the act of creating at all feels frivolous, but it is still worth it.

After her friend dies, Etty writes, “A poem by Rilke is as real and as important as a young man falling out of an airplane. That’s something I must engrave on my heart. All that happens happens in this world of ours, and you must not leave one thing out for the sake of another.” I read her words, and heard: Yes, your challenges do not compare to those of the Holocaust, and also, that game of comparison is not useful. I heard: You don’t have to wait to feel better before beginning to create, so start now, because nothing is promised. And through making, she told me, you will learn much more than you would learn through just thinking about making.

This being sick and doing it anyway, and trusting that what you create may be of use even though, or perhaps because of, the ways you’re sick: It blew my mind. If I waited for a different version of me, a version that felt as well as I looked, I’d be waiting a very long time to begin. I might miss out on my own life. And my wants and dreams might curdle inside me. So I started, even though I wasn’t ready, and the starting was its own process.

I wrote, and I focused on healing; within three months of reading her book, I was well enough to apply to jobs. Within six months, I found a part-time, non-profit job that paid just barely enough to live on, moved to a small room in a shared apartment that I could afford, and met three radical Jewish women to collaborate with and learn from. I painted my walls light blue and wrote at a heavy wooden desk. My bedroom window looked out onto the eastern sky and the sounds of sea lions were in my ears at night. Within a year, I began applying to writing workshops to learn more about craft. I tried to let other people tell me no instead of telling it to myself preemptively.

Almost two years after reading Etty’s book, while on scholarship at a week-long workshop for nonfiction, I sent my first essay about endometriosis to a feminist anthology, and it was accepted for publication. I remember walking towards my temporary mountain home one night after a reading, wanting to yell with how grateful I was, with how much more I still imagined and wanted. A stream was rushing under the bridge I needed to cross to get to the main road, and none of my friends were answering their phones, forcing me to just be with myself. I stopped and sat on a bench, staring up. The stars were crisp in high mountain air, and the body that was sometimes still my toughest adversary felt filled that night with buzzing potential.

Etty said I could be chronically ill, in far better political and societal conditions than she experienced, and yet I was allowed to create, and to take my inner life seriously, and nurture it. Over the seven years after reading her journals, I wrote hundreds of thousands of words (“slowly, steadily, patiently”) and I edited and rewrote until I was closer to satisfied with them. I wrote essays, short stories, and a book that I’d work on for five more years until a wonderful agent said, yes! I want this. I took my pain seriously, pursuing treatments with practitioners who also took my pain seriously, people who had solutions, or at least proposed treatments. I became healthier than I’d felt since being a child, or maybe since ever, as my endometriosis began healing, my lower back pain retreated, my exhaustion lifted, and the allergies I’d had since childhood disappeared.

It’s not all solved; I continue to be confounded by certain pains, frustrated and crying in bed some days, but there are others that I see now as friends, as forces pushing me forward, towards greater balance, whatever work is next: the healing of hyper-vigilance. And for that, and for the words of a Jewish woman writing in the early 1940s, who, before she got on a train headed to Auschwitz, handed her pages of writing to a friend and asked her to publish them, because she believed in the value of her own words, who taught me about creating as a woman in this body and century, I am forever grateful.