Catapult Year In Review

What If We Dreamed of Shared Support Instead of Private Space?

It really was the house to end all houses: impossibly big, impossibly beautiful, and, ultimately, just impossible.

Late one sunny Sunday afternoon, I text my brothers from a bar in Red Hook, Brooklyn. “Which painting hung over the fireplace in the living room in the big house?”

My brothers and I usually play this game in person, with a bottle of bourbon between us. Once in a while, though, I remember a moment that I can’t quite place, or a room that feels staged like a house for sale instead of actually lived in, and that’s when I reach for the phone. Over the course of our childhoods and early adulthoods, from 1973 to 1999, my family lived in seven houses, all in the same square mile of suburbia just north of the Bronx. They ranged from a seafoam-green shingle-style Victorian to a condominium with levels so confusing that a tipsy visitor who thought he was walking out the back door once fell out a second-story window. Two were owned; five were rented; all, regardless of size, contained the same conglomeration of furniture and decorations, like a traveling production of a play staged in a strange variety of venues. So, when the surviving cast members get together, we reassemble the set we built and struck together for almost twenty-five years.

How many doors were there in the kitchen at the green house?

How many fireplaces total?

When did they sell the piano?

In her memoir, The Yellow House , Sarah Broom asks, “How to resurrect a house with words?” All families reminisce, but in my family, all stories inevitably begin with the house we were in when they happened. Each one serves as shorthand for our circumstances at the time, and reconstructing them is our way of supporting each other, as if the houses we no longer have still hold us together.

One beer later, my brother texts me back: “The Bosch,” and suddenly I can see it. Painted at the turn of the sixteenth century, The Garden of Earthly Delights is a triptych depicting, in sequence, a serene Eden, followed by humanity run amok, and, finally, a vision of hell. It hung over the piano in our first house, shocking the sweet old ladies who came to teach us how to play; sometimes, when no one else was around, I stood on the piano bench and studied its tiny detailed depictions of orgy and torture. I didn’t look at it much in the big house, because we rarely used that room. If I had, I might have seen the literal big picture: paradise, party, ruin.

Reconstructing them is our way of supporting each other, as if the houses we no longer have still hold us together. To my father, who was born in a Quonset hut after World War II and raised in a railroad apartment in Brooklyn, the big house must have looked like paradise. That apartment was a dark, narrow space made even thinner and dimmer by the boxes of hoarded junk my grandmother insisted she needed. She grew up in a house owned by a mining company in Western Pennsylvania, until her family of ten was forced to live in a tent because my great-grandfather joined the union. So while my grandmother built walls within walls, my father dreamed of space. He wasn’t just investing in our future; he was renovating his history. When his business took off, he could have waited to see if the success was sustainable. Instead, he decided to buy the biggest property in town.

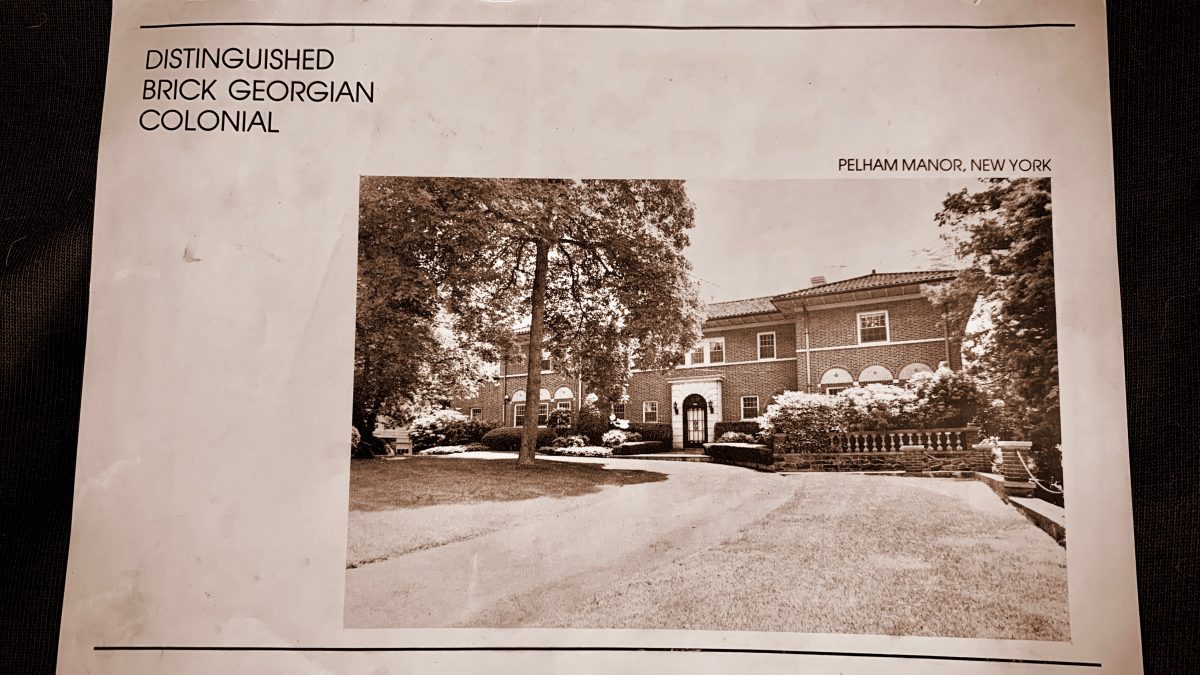

Photograph courtesy of the author

I love that the photograph now seems sepia, when in fact it’s from 1984. And yet our six years there also seem sepia—distant, ancient, strange. Our family pictures from that time look about as real as the ones we took in a beachside boardwalk tourist trap one summer, clad in costumes from a mythical Wild West. The brochure—the house had its own brochure—described it as “A perfect setting for the family accustomed to frequent entertaining and comfortable suburban living.” We were not this family. Regardless, we moved into the house in 1984, the spring I turned fourteen. It seems significant now that I cannot remember the first time I saw it or walked through the door; I do remember feeling immediately lost, as if I wasn’t supposed to be there. (Twenty years later, my psychiatrist will describe these feelings as “intrusive thoughts,” even though, as it turned out, I was right.)

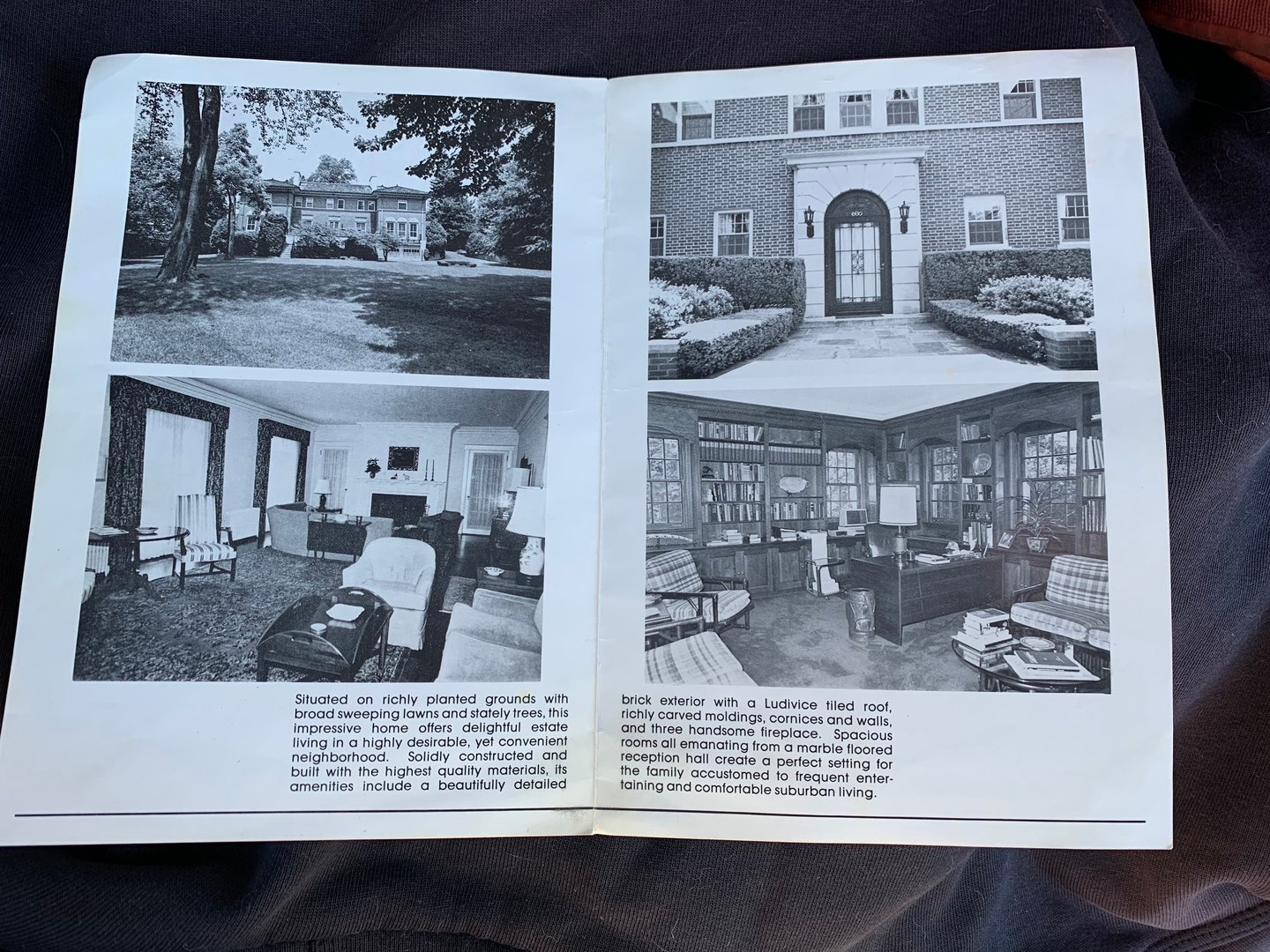

Photograph courtesy of the author

The house is still there, but the space isn’t. Later owners sold off half the lot, possibly to weather some misfortune of their own. I remember that, when things went wrong, my parents considered keeping the house and selling the land instead. But my father refused to give up the space, even if it meant we could stay. It really was the house to end all houses: impossibly big, impossibly beautiful, and, ultimately, just impossible.

Even when we thought we could afford it, the house didn’t quite seem real. My young cousins thought it was a restaurant. Another friend—from New Canaan, Connecticut, land of The Ice Storm and no stranger to big houses—mistook it for a school. Yet another, the youngest of a family of Persian aristocrats who fled Iraq, had a different attitude toward its immensity, confiding, “I’m so glad you have a big house too. People say things.” Some people said things; others were simply speechless. First-time visitors were often found on the front doorstep, looking up in wonder. Soon after we moved in, two girls I’d barely spoken to in middle school rang the doorbell and asked if they could “just look around.” It was—is—the sort of house that serves as a landmark in someone else’s imagination. After spending his life dreaming of space, my father now had more of it than he knew what to do with. Meanwhile, I dreamed of somewhere small and safe, somewhere I knew I could stay.

The house is a Georgian Revival, an architectural style defined by symmetry. Windows and wings and shapes are organized around a central impressive front door, and pairs of French doors line the back of the house, making it almost all glass. The rooms inside are also symmetrical, and the layout is I-shaped, which is apt; you have to think pretty highly of yourself to own a house like this. The design scheme, however, was anything but symmetrical, because my parents couldn’t agree on what they wanted. The library was decorated by a woman with classic preppy taste and filled with old wood and tasteful patterns, the adjoining family room by a tiny gay dynamo with brilliant orange hair who favored mirrors, marble, and mauve. My parents ran out of cash before they got to the living room that ran the length of the house, and it remained exactly the way it looked in the brochure. Walking across the first floor felt like visiting those dioramas at The Metropolitan Museum of Art that recreate rooms from different eras, except this history was all recent, and all of these eras were ours.

My room—rooms, really—was the former servants’ quarters ( or “Teenage Suite,” according to the brochure). Essentially, I had my own wing, with a bedroom, a studio where I drew and painted, and a beautiful blue-tiled bathroom. I’d rejected a huge bright bedroom in the main part of the house because it was too close to the master suite, and I wanted as many doors as possible between me and my parents. So I was alone, in a way I very much wanted but also very much didn’t need. On bad days, I didn’t even visit the main part of the house, just snuck in my own door, took food from the kitchen, and retreated up my stairs, down my hallway, to my room.

And I had a lot of bad days. My family’s roller-coaster financial status coincided with the onset of my bipolar disorder. For me, those changes are inextricably intertwined and mapped onto this house, which, like my mind, transformed from somewhere I should belong into a strange, unwelcoming space. I’d begun to change in ways I simply couldn’t understand. My sense of self was gone, as if someone had pulled a plug and simply drained the old me dry. Even today, forty years later, my memories of that house have a horror-movie quality: all normal, happy scenes were tragedies waiting to happen.

Christmas, 1984: I am a freshman in high school—Catholic school, kilts and all. It is our first Christmas in this massive house, and there is a massive tree and a massive party and massive amounts of gifts, which my parents have hidden in the wine cellar, because we have a wine cellar with no wine in it. My mother is pregnant at thirty-six, which is par for the course today but back then, nine years after the birth of my youngest brother, was very clearly what even Irish Catholics call an accident. I buy my mother a baby book for Christmas, and everything is right with the world, until it suddenly very much isn’t.

It isn’t because, after we open the presents and eat a huge breakfast with bacon and French toast, it becomes clear that my mother is having a miscarriage. Apparently, women who miscarry on Christmas Day in Westchester in 1984 with a house full of children and family and an obstetrician vacationing in Bermuda do not go to the hospital, or even to bed. Instead, my mother’s obstetrician, who in a few years will be arrested on charges of being on cocaine all the fucking time, tells her—and this is real—he tells her to get drunk to stop the contractions. He will tell her to miscarry her baby while serving a sit-down dinner for twelve and getting absolutely bombed.

My mother explains all this to me as it’s happening, but the explanation makes no sense: Pregnant women shouldn’t drink, but women having Christmas miscarriages should get so drunk that their bodies simply stop contracting. My sympathy for my mother is kept at bay by my fear about what happens when she drinks, especially when she’s sad, and the perfect Christmas in the perfect house goes black around the edges like a polaroid singed in a fire. Most of my memories from this time have a similar ruined quality, as if recovered from the ruins in the aftermath of disaster.

Fall, 1985: I am given carte blanche (my dad’s platinum Amex card) to decorate my room, and I abuse the privilege. My, ahem, aesthetic has evolved from the strawberry curtains and mahogany four-poster bed in my middle-school bedroom into a preteen approximation of Patrick Nagel’s cover art for Rio . The room is painted a perfect 1980s peach, with window treatments and bedspreads in a paint-spatter pattern. The furniture is modular white pasteboard crap from Room Plus that looks like it belongs in a space station; the decorous lady decorator who is chintzing the library downstairs peeks in and shudders. By the time I know I have made a huge dumb mistake, that this isn’t who I am at all, it is too late and I am stuck. And that’s pretty much the experience of living in this house.

April 1986: My sweet-sixteen party. No balloons for me (I still hate balloons): My parents hire a floral designer to cover the first floor with cherry blossoms and dogwood. The DJ and dance floor are in the living room; caterers set up café tables in the dining room. My parents invite a few friends over too, one of whom dresses up as Father Guido Sarducci from Saturday Night Live and dances to “Children of the Revolution” by the Violent Femmes. When Father Guido retreats to the library, one girl sticks her head in after him, comes back, and announces, “There’s a whole grown-up party in there!”

My father disappears; no one can find him. My mother is furious and keeps asking if I know where he is. The boy I like won’t slow dance with me, and I wish I could focus on that age-appropriate problem instead of whatever is going on with my parents. When my father turns up, he has his arm around a boy I barely know. “Later,” he hisses, when my mother asks angrily where he’s been, and he takes the boy to the phone to call his parents. It turns out that he was under the forsythia bush across the street, talking this boy out of killing himself, convincing him that life was worth living and that he should ask his parents for help. And he does.

For this and more I love my dad, but my mom isn’t wrong to wonder. Later that spring, late at night, the doorbell rings, and it’s the police. They have my father, who they pulled over for erratic driving. They have driven him home; another officer followed with his car. I do not yet know the term “white privilege,” but I know that his BMW and Brooks Brothers suit probably have something to do with why he isn’t in jail. The next day, he comes to my room and tells me he wasn’t drunk; he had taken some medication and didn’t realize how it would affect him. I wonder if this is the truth.

After this, everything starts to fall apart. I don’t really understand what my father does, but up to this point he’s obviously been doing it well. In April, my parents spend thirteen thousand dollars on my birthday; eight months later, I get a single sweater for Christmas. It’s not the lack of gifts that bothers me; it’s not knowing why things have changed and whether they’ll change back. My brain has started to swing between extremes.

Thanksgiving, 1986: I meet my boyfriend in one of the three basements. (Not the finished basement, with the wet bar and pool table and fireplace, or the two-car garage, but the middle basement, with the arched wooden door that opens under the patio and looks like it leads to Narnia.) We have sex on top of some rolled-up carpet, and the alarm beeps when I come back upstairs into the main body of the house. My father’s business is failing, so he no longer sleeps. When he meets me in the kitchen and asks what I’m doing, wandering around in the middle of the night, I tell him that I can’t sleep either, and it’s true.

April 1987: The house feels safer when it’s full, so I invite the entire junior prom over for an after-party. My parents circulate with sandwiches and serve coffee to the limo drivers who sit and smoke in the dining room until everyone gets back in the cars and heads to the Copacabana. That is the first in a series of epic parties, like the ones in ’80s movies, with rich drunk white kids in an elegant suburban house, except my parents are there too. I have probably never thrown a party that good in my entire adult life. Weirdly, these public, shared memories are the only ones that don’t go wrong—maybe because the house is finally doing what it was designed for. When my oldest friends say “your house,” this is the one they mean.

1988: As a teenager with undiagnosed, unmedicated bipolar disorder, my brain expanded and contracted like one of those paper fortune tellers we used to make in grade school and flexed back and forth on our fingers, each fold offering a different set of options but no way out. Bipolar is a spatial term, after all, and even before I knew what it meant, I thought of myself in those terms: I am rich. I am poor. I am smart. I am dumb. I’m an athlete. I’m a drunk. I’m beloved. I’m a slut. This is my home; I belong here. None of this is mine.

In her book Hatching: Experiments in Motherhood and Technology , Jenni Quilter writes: “Home is where you do not know how to hold back.” For years, I have held back, tried very carefully to not cause problems, to excel, to keep everyone happy. I have also been what I now know is called “hypervigilant,” waiting, always, for disaster to strike, not that I could stop it. Then I realized that, if I was the disaster, I wouldn’t have to wait. One week into the second semester of my freshman year of college, I carefully and deliberately shoved my hand through a window and then sat there, blood trickling down my arm, until the school called my parents to come and take me home, whatever that meant.

Spring 1989: I’m supposed to be getting better, which means seeing an analyst once a week, drinking and smoking weed in my room by myself every night, and traveling to the city on weekends to take acid with my friends. One of those trips evolves into a depression so deep that there is literal darkness at the edges of my vision, as if I’m looking down a tunnel at what used to be the world. I become deeply afraid of going to sleep; when I do, I wake up not knowing if I dreamed that I was screaming or if I actually screamed and nobody came to help me. Even though I’m ostensibly home, I’ve never felt farther from my family; the hallway between my wing and theirs seems impossibly long. I know that if I tell anyone how bad I feel, they won’t let me go back to school, so I keep it to myself, even though I want nothing more than to sit under a forsythia bush with my father and have him tell me it will all be all right. But he is either silent or absent, and my mother, who has gone back to work for the first time since before I was born, is exhausted. We all retreat to our separate squares of the space we can no longer afford.

It took me years to see that my family’s real estate follies were not just personal whims, but also responses to economic conditions over which they had no control. Summer 1989: The house goes on the market. When potential buyers come to view it, I follow them around, glaring, until the realtors have a word with my parents. After that, my dad brings sandwiches back from the deli during showings and we sit on the lawn and eat them, until the rich people drive away and we’re allowed back in. We can no longer afford the cost of the central air-conditioning, so on hot nights my brothers and I spread our sheets on the cool marble floors. Early that fall, the house is sold and we leave for good. That is the last house my parents own, and it’s the beginning of a spiral through a series of smaller and smaller houses that ends ten years later when, priced out of the suburbs, they move to the shabby little city next door.

It took me years to see that my family’s real estate follies were not just personal whims but also responses to economic conditions over which they had no control. Live up in a tent and you’ll long for walls; live in a tunnel and you’ll long for light; live lost in space and you’ll long for stable structures. I wonder what might change if we thought of home that way, if we dreamed of shared support instead of private space. Recently, in The Atlantic , Annie Lowrey described the effects of America’s current housing shortage on would-be homebuyers: “People make painful choices: To keep their housing costs in line with their income, millions of families do not live where they want to or in the kinds of homes they want to or with the people they want to.” As an apartment dweller for the last thirty years who only recently, at fifty, bought her first home, I find this darkly funny. Millions of people in this country have never lived where or how or with whom they want to, but since they weren’t potential homebuyers, nobody cared. But the American real estate market relies on this conflation of the personal and the structural: If I regard where I live as an extension of myself, the architectural manifestation of my place in the world, I can focus on what I think I deserve while ignoring the massive structural inequities that trap so many others.

Sarah Broom writes: “Houses provide a frame that bears us up. Without that physical structure, we are the house that bears itself up.” I did not bear myself up. I collapsed over and over for the next ten years, until another deep depression hit, and I was finally, successfully treated. Depression, for me, is still inextricable from space and still manifests in a sense of structural instability that seeps beyond my brain and makes wherever I am living seem both dark and insubstantial. Thirty years later, when my brothers and I cleaned out my mother’s apartment, we found boxes of documents from when my father mortgaged that house, and remortgaged it, and mortgaged it again. He tried so hard to bear us up.

When you lose your house and your mind at the same time, it’s hard not to conflate who you are with where you live. But where we live has nothing to do with what we do or don’t deserve. I wonder often who I’d be if I had grown up in just one place. Still, I was fed and housed and I know I was loved, even when I was not easy to love. If there is a tragedy here, it is that my family, like so many others, pinned our hopes and dreams and identities and resources on a house, instead of appreciating what we were actually building together: a structure that still, today, continues to support us.