Arts & Culture Rekindle

Mary McCarthy’s “The Group”: Three Queer Readings

“I think of McCarthy and ‘The Group,’ giving me language to understand myself before I even knew that’s what I needed.”

The first time I read The Group, I was a woman waiting to go to a women’s college. To me, someone who’d grown up a girl in rural upstate New York running track and feeling more than a little confused about sexuality and gender, the different agenda of a women’s college seemed radical. I’d come out as bisexual while dating a boy my senior year, and it felt like if I didn’t get to a place full of women, I might never get farther than that.

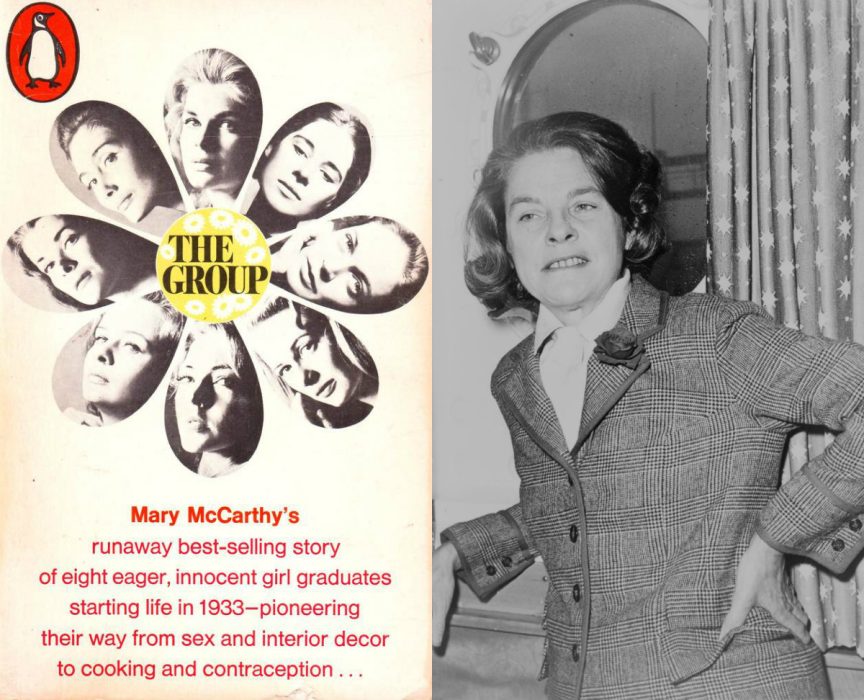

Published in 1963, The Group by Mary McCarthy was on the New York Times bestseller list for two years, but scarcely anyone younger than sixty has heard of it now. My copy is a battered Signet paperback that belonged to my mother, with eight daisies on the cover representing the eight Vassar College graduates characterized in its pages as they leave school and seek out husbands, careers, families, and lovers. Written a few years before Vassar started admitting male students in 1969, McCarthy delivers a nuanced satire of her classmates (she was Vassar ’33, just like her characters), while skewering a culture that expected them to educate themselves for society before returning to lives as docile wives and mothers.

The Group opens on the class of 1933, at the wedding of Kay and Harald just a few weeks after graduation, and ends with Kay’s funeral a few years later, in the same church. In between, she is committed against her will to a mental institution by her cheating husband. But it would be a stretch to say this drama forms even the main narrative of the story. The novel unfolds adjacent to these events, and we often see what’s happened to Kay refracted through the lives and conversations of her college friends: whispered behind her back, gossip traded between mothers and daughters, or in a newspaper item clipped by the family butler.

And then there’s Lakey, the most beautiful, most popular, and wealthiest of the group; the one who heads for Europe in the beginning and then is scarcely in a scene for four hundred pages, and yet it’s clear McCarthy likes her best. Lakey is reliable and loyal to her friends. (Although they are always wary of falling out of her graces.) Lakey doesn’t let a man determine her worth, and she’s the only one to evince any sign of growth or self-reflection by the end. And upon returning from Europe with a girlfriend—“The Baroness”—in tow, the Group realizes she’s also a lesbian:

They asked themselves, in silence, how long Lakey had been a Lesbian, whether the Baroness had made her one or she had started on her own. This led them to wonder whether she could have been one at college—suppressed, of course. [ . . . ] Obviously, [The Baroness], in her pajamas and bathrobe, was the man, and Lakey, in her silk-and-lace peignoirs and batiste-and-lace nightgowns, with her hair down her back, was the woman, and yet these could be disguises—masquerade costumes. It bothered [them] to think that what was presented to their eyes was mere appearance, and that behind it, underneath it, was something of which they would not approve.

The italics are original, and they emphasize that this is an entire book concerned with the matter of appearance. The appearance of acceptability. The appearance of transgression. The appearance of taste and straightness and political correctness, contrasted with the thoughts and feelings that happen behind closed doors, to which the novelist has the key. Lakey and The Baroness were the first depictions of queerness that I’d ever seen in a book, and I became electric with the idea that appearances could be so mutable, that on the outside I could look like a woman to others, while on the inside I could imagine myself as something else.

*

The second time I read The Group, I was enrolled in a women’s college, a sister to Vassar, but I felt out of place and didn’t know why. Often I felt like something was wrong with me because I failed to coagulate a group of friends around me. The friends I did make all came from wildly different backgrounds and rarely socialized with one another. An even greater source of anxiety was why there were certain corners of our conversations that made me feel uncomfortable, topics like periods and our bodies and those of men. This was especially noticeable in the women’s locker room with my teammates, who I spent more time with than anyone else, and yet I left each practice feeling like a stranger inside my body.

Kay and Lakey are the anchors around which The Group revolves, but the bulk of its pages are taken up by the stories of their friends. Libby, whose date tries to rape her in her own home before he realizes she’s a virgin and leaves in disgust. Priss, who finds herself a new mother trapped by her pediatrician husband in an experiment to prove to the medical establishment that if his flat-chested wife can successfully breastfeed their son, then the practice should be widely adopted. She watches from her hospital bed while her husband shakes up martinis and discusses her milk production with friends and family. And then there’s Dottie, who loses her virginity to a man who suggests she buy a diaphragm—which Dotties considers equivalent to a promise ring—only to stand her up later. She leaves the device under a park bench without ever using it and goes on to have a nervous breakdown, move to Arizona, and marry an oil baron she doesn’t really love.

I think about Lakey watching her friends from afar as they succumbed to the wishes of men, and as a few of them actually started families they found fulfilling against all odds. She’s described at the end as having a particular inclination toward children, playing enthusiastically with the offspring of the rest of the group. And yet, McCarthy never pities her; she is held up as an example of one who lives her life as she chooses, without men, and this is something the others can’t admit to being deeply envious of, and so they feel sorry for her.

I didn’t want to pity Lakey either, but I felt sorry for myself, and angry at my environment. There were side effects of a women’s college I hadn’t expected. I didn’t yet understand how to love my own femininity (it would take becoming a gay man to get there), and I felt hemmed in on every side. But the low was still to come. After graduation, my college cross-country coach put me up in her home while I was getting top surgery. I spent the night after the operation throwing up in her bathroom, and in the morning, I met her two-year-old daughter while high on painkillers. It was an extreme act of generosity, and we haven’t spoken since.

Like Dottie hiding the pessary under the park bench, there were parts of myself then that I didn’t feel were right for human consumption, things I felt I needed to keep locked away and separate from the rest of society. If someone else from that part of my life did glimpse them, then I shouldn’t burden them with my presence any longer than necessary.

*

The third time I read The Group, I had found a way to reconcile outside appearances with my inner identity. Coincidentally, I could now attend the same women’s college once more. In the interim, my alma mater had broadened its admissions policy to admit and graduate women, trans men, trans women, and those who identify as non-binary. It’s one of the most progressive policies at a women’s colleges.

Of course, there were other trans students enrolled while I was there. There have always been trans students at women’s colleges in the same way that I have always been trans without appearing so. Still, having our presence encoded in the institution’s DNA does make stepping on campus feel different now, less fraught. Recently, I returned to my college as part of a panel; I was nervous, but wound up utterly amazed at how much like a homecoming it felt. Shy students, both trans and not, approached me to ask for advice. I made new friends among alums I didn’t know. Only once did a kindly older professor refer to all us visiting alums as collectively female, and immediately after he stuttered deliciously.

The same night that I returned from the panel, I menstruated for the first time in seven years, only this time it was as a man. It was the result of a mix-up with my prescription, but I had never had a period as a man and I was horrified, and then in turn disgusted with myself for being horrified. When I was a woman, periods were inconvenient, often uncomfortable or painful. When I started taking hormones, I was excited for this monthly annoyance to go away, and I was lucky that it did. (It doesn’t always for all trans men.) During the period of overlap as my ovaries slowly went into torpor, I thought of it as something leftover from a previous visitor to my body, something that didn’t really belong to me, that I was just keeping it safe while she was busy, like I was holding her purse. But when it came back, there was no other owner. It was mine, and although I tried to find a way to talk about it without saying the words “my period,” I didn’t have the language to describe what was happening to me.

I think of McCarthy and The Group, giving me language to understand myself before I even knew that’s what I needed. I think of the women in The Group, whose bodies men thought they owned, and could do with them whatever they liked without consequence; Lakey, whose body and destiny was her own; and I think of the woman (myself) whose body I devoured without perhaps realizing everything about it. In some ways, it was nice to see that we are still the same person, that I haven’t completely cannibalized her. She and I will always make up our own strange little group of two, and she can still catch me unawares at times and say: See? I don’t feel sorry for you. Don’t forget where you came from.