How To Shop Talk

When I Think About Giving Up Writing

I was happy raising my kid, living my life without worrying about writing.

We’re two years into my daughter’s life and we still don’t quite have a bedtime routine. It skips around depending on so many variables, and while she’s a good sleeper once she’s actually asleep, getting there is more of a process than a routine. Often by the time she’s out, I am too, having drifted off in the dark along with her.

I have plenty of friends whose children can be placed in a crib without fanfare, and it seems like a miracle, until I remind myself that that kind of sleep can be taught. I’d read the posts in the Facebook groups devoted to sleep training, but we’d gone against everything suggested. In a way, my willingness to proclaim failure in this area is to try and foolishly rebel against how regimented life is with a small child— let me be carefree with this one thing! —because despite the lack of a clear bedtime routine, other parts of our lives follow precise, sometimes exhausting, military-timed patterns.

They aren’t, however, without certain pleasures. I do morning daycare drop-offs, for instance, and even if nothing has worked out, even if we’re late and there were tears, by the time I’ve dropped my daughter off and am settled back in the car on my way to work, I can at least tick off the first To Do box of the day. I’ve accomplished something , and it feels good. After leaving daycare, I drive towards Toronto’s skyline of condos, skyscrapers, and the CN Tower, take an exit along the lake, and then turn into a west-end neighborhood, where I work for eight hours until I make the same drive back in the opposite direction.

In the fall, while stuck in a left-turning lane, I daydreamed an essay about commutes, my own history of them. My first real job was at an accounting firm where the majority of my clients had offices in industrial parks at the edges of suburbs. I’d drive to these unfamiliar places and sometimes in the early morning I’d see deer in the lonesome farm fields that hadn’t yet been repurposed into subdivisions or warehouses. When I was pregnant, many years and jobs later, my commute went north of Toronto. Morning sickness hit me at the same time each day, always during my drive, so I kept a stash of plastic bags by the passenger seat. I could trace the commute by the strip mall parking lots I pulled into to vomit.

I wanted to assign meaning to these commutes, connect them to each other so they weren’t just non-events, random occurrences, wasted time. I could do that by writing an essay, I thought, padding it out with some research. It wasn’t until another commute a few days later that I realized I didn’t have time to write it.

*

I signed a contract to publish my second book in my last trimester, and then edited it while on maternity leave. I’m not sure I would’ve been so disciplined without a deadline looming over me, and while these moments were sometimes overwhelming, I also loved them because they connected me to myself, to who I was: a person who wrote.

These days, writing is often the first thing dropped. It’s hard to believe it was easier to work with words in that postpartum haze, but I so badly needed to write and maintain my writer self that I did it no matter what. In the car, it occurred to me that maybe I didn’t have this need anymore. Maybe thinking up that essay was enough; it didn’t have to be written down. Maybe I didn’t have to write anything down.

For the next little while, on my way to and from work, my thoughts circled in a neat little loop: If I wasn’t going to write that essay about commutes, what would I write instead? I wasn’t sure, and while in the past this would have left me panicky, at that moment, it didn’t. It was just a fact. Maybe I wouldn’t write then, at all, ever, again.

I imagined quitting writing. Just stopping. I don’t write for a living, so I could do it—let it slip away and no one would ever know. I wouldn’t tell anyone, either, or make a big deal of it. Part of me welcomed the idea, the way one welcomes a good night’s sleep: as a relief. The unclaimed time and freedom would be interesting. I could take pottery classes or start jogging.

Quitting has bad connotations—there is nothing more deflating than giving up—but I wasn’t exactly sure what I would be sacrificing if I stopped writing. Quitting couldn’t be that bad if you were happy with the alternative, and I was happy raising my kid, going to work, living my life without worrying about writing.

*

While pregnant, I read Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work to steel myself for the months ahead. I also read Knausgaard, absorbing the parts about the tedium of being at home with a child and the horrors of birthday parties. I learned about the pressure of being family-portrait perfect; of the burdens mothers take on regardless of how equitable a relationship might be. Which is to say, I went into motherhood already feeling a bit wary of maternal happiness, knowing it often comes with a wealth of sacrifices, inequalities, and injustices.

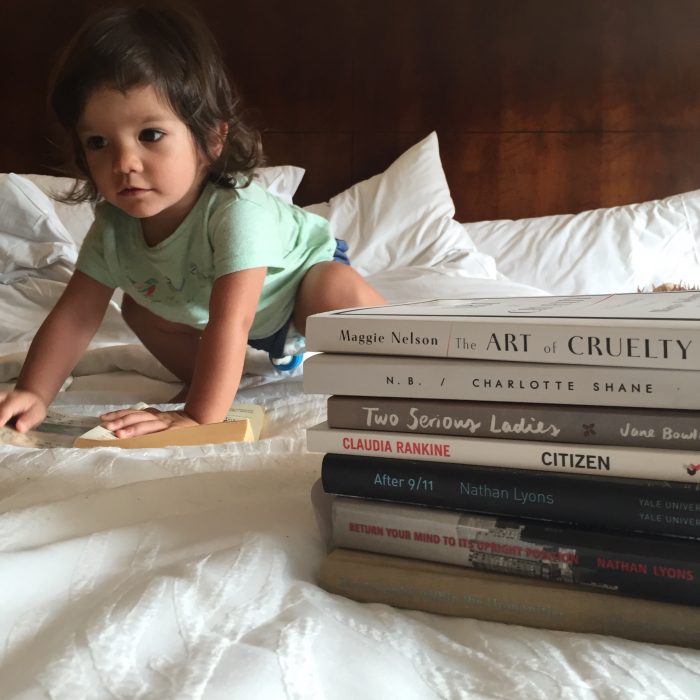

photo courtesy of the author

After schooling myself so well, I sometimes think I must miscalculate the happiness my kid has given me. It’s not that the hard parts aren’t hard, because they are—hard, boring, scary, complicated—and it’s not that they’re rare, because they aren’t; but the simplicity of my accompanying, overarching happiness was unexpected. It was as if I’d prepared myself for a natural disaster and faced a mild rainstorm instead. Or, I think, am I just trapped in the eye of a hurricane, unaware of what’s swirling around me?

Except I do have a tip-off: how okay I am with the idea of quitting writing. The desire to write has been a constant throughout my entire life. It seems suspicious that I’d consider giving it up now.

I asked myself exactly why I wrote before. A large part of it was a kind of striving towards something, a reaching—so what was I reaching for? What question was I trying to answer? Maybe I was striving for happiness, and thought writing was the most fulfilling path toward it. Maybe now that I had a child, those pleasure receptors were being satisfied in other ways. But then I remembered Odysseus’s men blissed out on lotus flower, having to be dragged back to their ship and tied to the prow until they remembered the point of their journey: Happiness can be a stupor.

*

When my first book was published, I was thirty years old and the idea of children was on the horizon, a pleasant sailboat dotting a sunset, close enough to recognize its shape but still too far to identify its passengers. I did a reading with a woman with two youngish children—I don’t know how old they were, because at the time, such numbers didn’t mean anything to me. I heard her saying goodnight to them on the phone after the reading. When she hung up, I asked her if it was hard to write with kids.

“It’s not bad now that they’re older,” she said.

“What about when they were really young?”

“I don’t know. I didn’t really try.”

“Did you mind?”

“It’s funny,” she said. “I didn’t.”

What I took away from this conversation was that if I ever found myself in a similar situation, I should write through it so that I wouldn’t, years later, regret that I hadn ’ t. What I didn’t take away was that she hadn’t actually used the word “regret.”

*

In an essay from Elena Ferrante’s Frantumaglia called “Writing Secretly,” she writes:

As a girl, I had an idea of literature as all-absorbing. To write was to aim for the maximum, not to be content with intermediate results, to devote oneself to the page without half measures. Over the years, I’ve fought against this overestimation of literary writing with an obstinate underestimation (“There are many other things that deserve unlimited dedication”).

I read this and realized that maybe this was closer to what I was feeling: less a desire to quit and more an “obstinate underestimation” of writing. Like rebelling against sleep training, turning my back on writing would be an act of self-preservation, a “you can’t fire me because I quit!” flounce. It was much more convenient to tell myself I was done with writing, that I could be happy without it, than it was to acknowledge that I didn’t have the time to devote to it.

My husband and I have a painting by a friend who is an incredible painter. Life got in the way, and when we saw each other recently, almost nine years had passed since our last meeting. I asked her about her art and she told me, matter-of-factly, that she was quitting. Her reasons made perfect sense, and what was also comforting was that her quitting had nothing to do with children—she doesn’t have any.

“I don’t believe you’ll quit!” I said. We laughed about it, but I know my glib response to her carefully thought-out reasoning might have been annoying. In retrospect, it was my way of saying, “Don’t quit because I love your paintings,” but also, selfishly, me telling myself that I didn’t believe I could quit writing.

In her essay, Ferrante says that eventually she “reached an equilibrium,” balancing that over/underestimation into something reasonable. I don’t know how she did it, but at least I know it happened. And as time passes, I wonder if I’m confusing the various demands and joys of motherhood with those of artistic practice, conflating them when really they’re two separate things that might overlap but are essentially independent.

*

It’s unrealistic that my relationship with writing would go without challenge for so long. It makes sense to me that I would finally question it at a point in my life when I had less time to work on it. As for whatever happiness I feel now, it’s not that I shouldn’t trust it—I do, and am grateful for it.

But maybe it’s not a bad thing to also hedge for a future version of myself who might not be so generous; who might look back and think, If you had sleep-trained, you could’ve gotten so much more accomplished . If you had just written a little bit, it would have eventually accumulated into something bigger .

The truth is that I continue to write; I haven’t stopped. But I want to acknowledge the feeling of wanting to quit at times. I want to acknowledge it the way I wanted to acknowledge all those minutes and hours waiting to merge onto the highway while I commuted to and from work: not as lost time, but markers of time, moments to look back on to understand who I was then. With writing, if this means that there are stretches where the words come slowly, so slowly they seem like they might as well not exist, I just have to trust that they’ll come back. As they always have.