Don’t Write Alone Columns

Bookseller Spotlight: Shirikiana Aina Gerima of Sankofa Video, Books & Café

The Washington, D.C. bookstore “represents the generation of people who kept Black publishing and Black voices alive while they were under attack.”

This is the second installment of “ B ookseller Spotlight ,” a series of features by Steve Haruch on the business of bookselling.

When the COVID-19 pandemic first hit, Sankofa Video, Books & Café in Washington, D.C., like so many other small businesses, shut its doors in response. Then, co-owner Shirikiana Aina Gerima gave her buyer instructions that had once been unthinkable: take down all the books and send them back. It was like having cash sitting on the shelves, and cash was one thing they couldn’t afford to let collect dust.

“I took pictures of [the buyer] taking books off the shelves,” Gerima remembers with a laugh. “Put it on social media, let people know we are doing our best. I don’t know what I was thinking, really.” Like many independent bookstores, Sankofa faced an uncertain future, not knowing when they could reopen or how they could sustain the business they’d built over two decades. Then, something terrible happened.

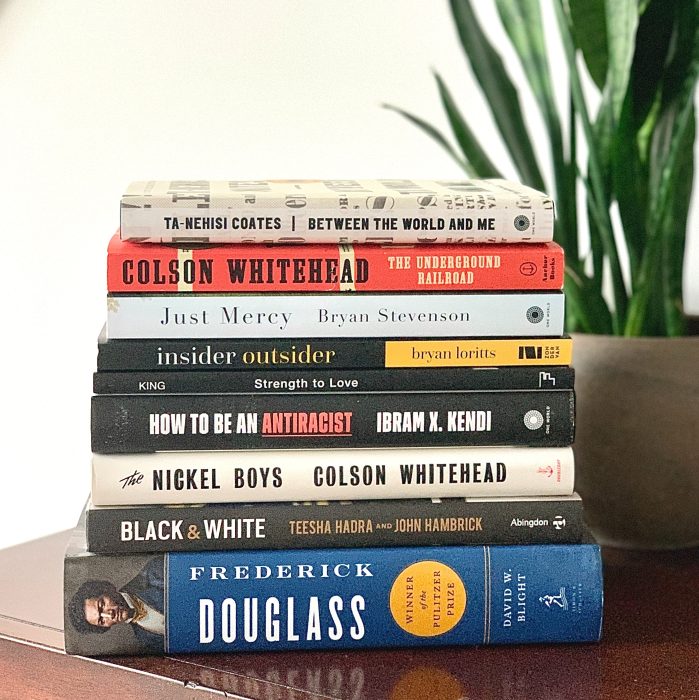

The murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin ignited a summer of protest and, in turn, prompted the creation of countless anti-racist reading lists and the Black-owned bookstores to buy those books from. “We were very, very sad about what it took to get people to read,” Gerima says, “but we were very glad that one of the outcomes of this moment in history was people trying to figure out what the heck is going on.”

Suddenly the challenge of being closed to the public became the challenge of fulfilling orders as they poured in from all corners of the country. The Gerimas, whose experience up to that point was built around physically present customers, had to learn a new way of doing business—and quickly. On the plus side, this meant their workers were able to pick up more shifts after effectively being furloughed. It meant getting their inventory online. And most of all, it meant survival.

The anti-racist book boom of 2020 was a lifeline for independent bookstores across the country, but Black-owned shops in particular became a focal point. Educating oneself about racism seemed to intersect with actually doing something. “That response [of an] otherwise guilt-ridden white public was very helpful, and kept a lot of stores open,” Gerima says.

For some Black booksellers, this sudden bounty could be a mixed blessing—customers demanding overnight shipping, complaining when books sold out, and pinning their desperate hopes for quickly defeating racism on books and suddenly overwhelmed retail workers. But for her part, Gerima has no complaints: “I have not talked to anybody who thought it was a burden.”

Still, once the initial crush of orders subsided, business slowed again. Sure, people needed time with all the new books they had just acquired, and a lot of it was not exactly easy reading. But, as Gerima puts it, “I would hope that [the] public that felt it was so important to support independent bookstores continues to think that way.”

The loss of life that propelled discussions of systemic racism in summer 2020 still weighs on her, as does all the loss that preceded it. Before George Floyd there was Breonna Taylor. Before them there was Ahmaud Arbery. Before Ahmaud Arbery, there was Philando Castile and Walter Scott and Eric Garner and Michael Brown and all the others, the names and lives stretching back into the past, to Emmett Till and beyond.

*

For Gerima and her film-director husband, Haile, their past is one shaped “by the cauldron of American racism.”

Haile Gerima first traveled to the U.S. as a student. “He came here thinking he was Ethiopian,” Shirikiana says. “America taught him he was Black—and another word that starts with an n —real fast.” This experience shook him but only strengthened his resolve. America might think it knew him better than he knew himself; he might say the same about America.

Their past is one shaped “by the cauldron of American racism.” Shirikiana Gerima’s father arrived in Detroit from Mississippi and, as she puts it, “tried to raise a family within the same environment.” In other words, different city, same cauldron. To survive in a world that is hostile to the color of your skin, Gerima says, you need tools. “Books and movies,” she says, “are some of those tools.”

Gerima credits an upbringing filled with reading and studying, which built a base of knowledge that has kept her going through the most difficult times. She first found inspiration in the great Black writers of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, like James Baldwin, Frantz Fanon and Toni Morrison, as well as the thinkers who influenced them—turn-of-the-century voices like W.E.B. DuBois and Marcus Garvey.

“When you have that kind of rearing, and come from those kinds of backgrounds, you have a faith in your community,” Gerima says. “You don’t have to wait for an era to say, ‘Hey things are rough, let’s do this, people need this now.’” In other words, when the notion that Black lives matter suddenly dominates the news, your shelves are already heavy with books—decades and decades of them—that not only make that case but put it in a variety of historical and geographic contexts. It’s the same faith in community that assured Gerima and her husband that they could find an audience for Sankofa , a film they produced and, later, a customer base that would support Sankofa the store.

“We felt armed,” Gerima says. “We felt we had the weapons to share, to help people develop intellectually and culturally and spiritually. We just needed a space to kind of help it along. The material is there.” Like any good bookseller, she is more than happy to talk about the material.

*

When Sankofa opened in 1998, VHS was the format of the day, and videotapes for rent outnumbered books for sale on the shelves. The reason the store exists, as well as its name, comes from the film industry.

The Gerimas are both filmmakers. Haile is a UCLA graduate who was part of a group called the LA Rebellion, who were known for rejecting the rules of standard Hollywood storytelling. He has directed twelve films and has taught at Howard University. His 1982 film Ashes and Embers was re-released in 2016 by Ava Duvernay’s Array collective. Shirikiana got her start writing and directing the 1982 short-form documentary Brick by Brick , about gentrification in poor Black neighborhoods in Washington, D.C. Her many credits include the documentary Through the Door of No Return , which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.

Photograph courtesy of Shirikiana Aina Gerima

In the early 1990s, the Gerimas teamed up to independently produce a film called Sankofa , in which a young African American woman working in Ghana finds herself suddenly transported back in time to a slave plantation. The script took pains to avoid stereotypes of plantation life, choosing to focus on the relationships among enslaved people and, ultimately, their growing will to survive and resist.

Sankofa was picked up for distribution overseas, and was nominated for a Golden Bear at the 1993 Berlin International Film Festival, but the creative team had trouble finding a deal in the U.S. Sony Pictures showed some interest, and so the Gerimas sent them the film—literally, since in those days, film was a physical print in a canister. While the studio thought it was a good film, they replied that they didn’t think they had an audience for it. Could that have had something to do with the fact Sankofa featured no white main characters, and had no white producers attached to the project? Whatever their reasons, stateside distributors never picked it up.

“They can’t see anything that hasn’t been interpreted and cleansed for them,” Gerima says of the big American studios, “so we took it out ourselves, which is fine.”

That meant launching a pre-Internet grassroots effort to drum up interest, raising some money to hire a promoter, and renting out the erstwhile Jenifer Theater in Washington, D.C. On opening night, and for weeks thereafter, crowds lined up around the block. Having found success with this model, the Gerimas made community-based distribution their template and repeated it in other cities.

[Sankofa] means going back to your past to understand your future. Over the next two years, the experience of exhibiting Sankofa around the country proved to the family that they could connect with their community and find success. When a building across from Howard University became available, one formerly owned by Omega Psi Phi fraternity, they jumped at the chance to open their own space dedicated to film and literature. “We didn’t like the idea that people read books and don’t read culture; that is, they had no lexicon for reading visual meanings,” Haile told Black Power Chronicles in 2020. “So we felt that we need[ed] to create a cultural center where people read visual stories and books.” Calling it “Sankofa” just made sense.

“Sankofa is an Adinkra symbol,” Gerima explains, referring to the West African culture centered around Togo and Ghana. “It means going back to your past to understand your future.”

The store’s vision is broad and international. Describing the kinds of writers, books and publishers Sankofa supports, Gerima cites Ann Petry (“I don’t know if she was ever appreciated the way she should be”); Haki Madhubuti and Third World Press (“a small press, he’s a poet, essayist and publisher as well . . . one of our main suppliers”); Red Sea Press out of New Jersey (“an amazing array of titles that nobody else would bother with”); Black Classic Press in Baltimore (“he keeps books in print—Walter Rodney and books that you just don’t ever want to go out of print”); and other lesser-known writers and presses.

Hannah Oliver Depp, owner of Loyalty Bookstores, says, “Sankofa represents specifically the generation of people who kept Black publishing and Black voices alive while they were under attack.”

*

As harrowing as it has been to see white supremacist violence resurfacing, Gerima knows these are not new struggles. When asked if the movement that bloomed all over the country in 2020 is something lasting and sustainable, she is hopeful, but not naïve.

“I don’t know. I’ve lived through enough of these to say that the system is very, very malleable,” she says. “And it’s very good at figuring out how to incorporate a couple of things until time passes and we forget about it.” Experience has taught her that eras come and go. What matters is what we do to support what we believe in. “If you want an era to bloom into its best possible manifestation,” she says. “then you have to feed it.”

She means culturally and intellectually; with generations of knowledge at the ready, a more just future is within our grasp if we take the time to learn. But Sankofa is also a place to be nourished in the literal sense. The “café” part of “video, books and café” includes a roster of sandwiches named after Black filmmakers—from the Ava Duvernay (hummus and falafel wrap) to the Spike Lee (roast beef, bleu cheese, red onion) and even the Julie Dash (tomatoes, spinach, hot sauce and Sankofa dressing).

And, just as not all independent bookstores serve sandwiches named after Kathleen Collins (salmon, pesto, capers), not all independent bookstores avoid growth for the sake of growth.

Gerima sees value in staying the course. “Sankofa is fine with being small and productive because we know that the ability to control what we sell and how we do things diminishes with size,” she says. Their brush with big-time movie studios taught them that going more commercial can mean compromising on one’s desires for the sake of commercialism. “Independence, for us, means we can do what we want to do.”

And while she senses the threat of behemoth corporations that would gladly crush the likes of Sankofa, Gerima enjoys the position they’re in. “I feel like my strength, and the strength of people who want change, comes in independence,” she says. “When you don’t have the fear of having someone looking over your shoulder and saying, ‘That’s a little bit spicy, we don’t understand that, or we don’t have an audience for that, who’s going to buy that book, no one’s going to understand that slang,’ then you really get that genuine texture—and it’s so exciting. That’s where my hope lies.”