People Other Selves

Some Girls

“I made Ryan feel like his New Balances were snakeskin boots.”

I was dating the son of a preacher man and yet I was the unholiest of girls, which was why Ryan liked me, and liked me enough to introduce me to his father. We were heading north on I-95, southern prairies turning to slabs of granite as we hurried along the eastern seaboard in Ryan’s dark green Mazda toward Rhode Island, where Ryan’s dad pastored. It was midsummer. We’d been together for nearly eight months.

Ryan was smart. He went to Duke, was twenty-one to my nineteen. He had never so much as smoked pot. I tried to be good for him. I quit smoking and everything else. But I kept the bleached blonde hair, the costume jewelry, and vintage leopard fur coat, as well as the punk rock impulse not to give a damn about much of anything. I was dangerous and I knew that made Ryan feel like his New Balances were snakeskin boots. He had swagger with me.

Our road trip began as hopeful as most road trips begin: the surge of freedom in our veins, music emanating from the dash. As we careened across state lines, a perfectly golden afternoon unfurled its flag, and I unbuckled everything at Ryan’s lap and proceeded to give him a blowjob. This was the kind of thing Ryan had always dreamed of but would never request aloud, and maybe I knew that, and maybe that’s why I felt so bold beside him. Afterward, I rolled down the window to spit, but the southerly wind behind us whisked his semen forward, smacking the windshield with a thwack . Horrified, Ryan quickly employed the wipers.

“How’d I know you’d do something like that?” he said.

I winced. I didn’t know how to not be me, and because I wasn’t the kind of girl Ryan would usually date, I managed to always feel like an exaggerated version of myself, an actor playing a part. Me, already wild, but wilder somehow because that was what was expected of me. Earlier that day, I told Ryan that I’d never even been to church.

“Never?”

He couldn’t believe it. His voice squeaked a little when he was agitated.

As kids, my brother and I attended after-school care at a Baptist church where we memorized passages from the Bible, but I’d never heard an actual sermon, never taken a bite of Jesus’ flesh, never been dunked into a lake for salvation.

“Will we have to go to your father’s church?” I wondered.

“Probably.”

“Oh, god,” I sighed. “What happens there?”

“It’s not so bad,” Ryan said. “You just sit there and take it. It’ll make my father happy, so we have to do it.”

So I would go to church, then, because I really did love Ryan. With him, I did all sorts of things I thought I’d never do. I’d helped set up a tent outside of the campus auditorium where hundreds of Duke students camped overnight to score tickets to the basketball game against the rival UNC Tarheels. That night, we made s’mores over a campfire with Ryan’s nerdy friends from the engineering department. When I bummed a cigarette from the group’s lone smoker, Ryan shot me a look.

“Just one,” I said. “Come on.”

Later, I pulled him into the tent and we fucked as quietly and motionlessly as possible to avoid detection.

Afterward, Ryan refused to kiss me.

“What’s wrong with you?” I asked.

“Sarah,” he said, turning away. “It’s like kissing an ashtray.”

*

I met Ryan in Chapel Hill through my high school boyfriend Jeff, a dead ringer for Thurston Moore, whom he happened to be obsessed with during the semester we dated, when I was a sophomore. After our breakup, I listened to Pavement’s “Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain” for six months on repeat—it’d been the soundtrack of our romance—and cried in my bedroom at night. Jeff, who was a junior, got really into math and preoccupied himself with taking practice tests to ace his SAT score. He quit his noise band and began buttoning his shirts all the way to the neck. I told myself it was nothing personal—everyone has their own unique method of grieving. He earned a perfect score on the math portion of the SAT and a free ride to Duke. But he never lost his taste for good music, and in college we’d bump into each other at shows and house parties, which was where I met Ryan, who’d befriended Jeff when they moved into the same dorm freshman year.

Ryan was smitten with me, and I was intrigued by the guy who could wear the nerdiest navy Duke windbreaker to jam out to a three-piece lesbian metal band. He and Jeff stood out in a sea of crustpunks. I shuddered at Ryan’s floppy running shoes and baggy jeans, but still I let him usher me from the party after midnight. I let him talk about music while we drove around, searching for a snack.

“I DJ at the Duke radio station,” he told me. “I have a show Monday nights.”

“Impressive,” I said. We pulled into a grocery store.

I’d worked a gig at Greensboro’s college station since high school, but said nothing of it. “What do you play?”

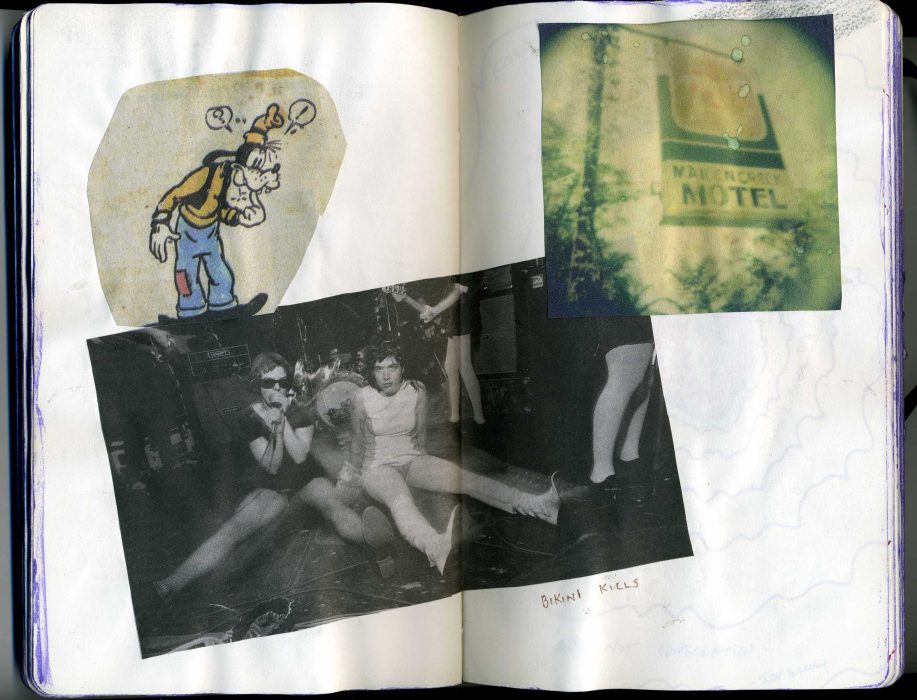

Ryan had only discovered the indie music scene in the past year and now foraged for records every chance he got, struggling to catch up. He went on and on, giddy as a billygoat, about Built to Spill, Sebadoh, Spiritualized, the Pixies, Wilco, REM. I listened, bemused, as we strolled down grocery aisles. I could’ve easily sounded bitchy had I interjected—my love affair with indie and underground music had started at age twelve. By adolescence, I’d become swept up in the Riot Grrrl movement—I’d danced onstage with Sleater-Kinney at age fifteen, the same year I’d corresponded with Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill, mailing her my homemade zines and angsty lamentations about life in a Southern town. In return, she’d sent me stickers and handwritten letters and a rape whistle.

“I’m going to see Beck next month,” Ryan said. “In Washington, D.C. You should come with me.” We stood in the checkout line, Ryan with his debit card in hand, ready to pay for my potato chips, juice, and, at the last minute because I knew he wouldn’t say no, the latest issue of Nylon magazine.

“Maybe,” I said.

“You know,” he shrugged. “I’ve always wanted a girl like you.” He blushed. “It’s just, I have a girlfriend.”

“Oh.”

“But I’m breaking up with her.”

“Don’t do that,” I said. “I can’t promise you anything because we’re in a grocery store together.”

But I wanted to know everything about her, and Ryan was the forthcoming type of guy, the kind bubbling over with information, no trace of mystery. Ryan was as clear and readable as a neon sign flickering in the night.

Her name was Katie, she was a student at UNC-Chapel Hill, she had shaggy brown hair and thick bangs that hung like a curtain over her eyes, and, by the way Ryan described her, I could tell she was just about the sweetest girl on this planet and that he found her tragically boring. They were perfectly suited, but Ryan didn’t want perfect. He wanted me.

I understood immediately that what Ryan wanted from me was the sensation that he was not average or wholesome. Ryan was a blender, adrift in a sea of white men. With his glasses, lankiness, and homespun face, he was kind and unremarkable. And I was the rabble-rouser who liked him for exactly the opposite reason. I liked Ryan because he was so considerate, so regular; he didn’t need to leave home to panhandle or jump trains cross-country, and he didn’t have the attitude or drug problems of the musicians I knew, with their hydraulic egos and squalid bedrooms. With Ryan, I felt publicly acceptable, validated.

After the grocery store, we parked in front of a deserted golf course and had sex under a streetlight on the hood of Ryan’s car. Afterward, he dropped me off at my friend’s dorm room. The next night, he broke up with Katie. We made plans to see each other again, and made plans to see each other again after that, and soon I was accompanying him to Washington, D.C., where his Duke radio connections had scored us tickets to an acoustic concert with Beck for industry insiders. We stayed in a hotel with windows overlooking what could’ve been Paris for all my excitement, having sex all night, and I let Ryan come inside me because I was on the pill, which I’m pretty sure was the first time he’d ever done such a thing.

*

The next day, after staying overnight at Ryan’s friend’s apartment in New Jersey, we pulled into his father’s house. It was late afternoon. Fred was waiting for us in the yard, his antique cottage behind him, a gravel driveway bifurcating his lawn and the start of the church’s right next door. Fred was remarried to a spunky and liberal woman named Jo, who took a liking to me immediately because I was essentially the younger version of her, because we both recognized a kindred soul out here in boonies Rhode Island, among such reserved men.

Fred was boxy and clumsy, with outdated frames and hiked-high pants like a virginal high school biology teacher. Jo was blonde and kind-faced and I would spend a majority of the trip wondering about her and Fred’s sex life.

Ryan’s parents had divorced when he was young. In the seventies and eighties, they’d served as missionaries—the reason Ryan was born in South Africa, and the reason he was uncircumcised, he’d once explained.

Fred and Ryan hauled in our bags while I took in our quaint arrangements. Everything antique, everything white, with sudden flourishes of blue. Nature paintings hung from vintage wooden frames against patterned kitchen wallpaper of rust-colored roosters. Slack from travel, I perked up when Jo procured four glasses and a chilled bottle of white wine from the fridge.

I was technically underage. That had never stopped me, but I knew that his dad was a stickler. I was glad Ryan hadn’t told them my real age. In fact, they seemed to know nothing about me.

“Ryan says you’re in college—are you at Duke, as well?”

“No, about an hour or so away,” I said, “at UNC-Greensboro.”

“Ah,” Jo said. “And what are you studying?”

“English,” I replied.

“English?” Fred interjected. “Might as well be Ryan with these do-nothing majors.”

I chuckled uncomfortably. “Actually, I want to be a writer,” I said. “Not that that’s lucrative, either.”

“Better than Ryan here,” said Fred. “A major in sociology? Did he ever tell you he could’ve gone to journalism school at UNC, and didn’t want to?”

“He never told me,” I said, glugging the wine.

“Dad,” Ryan said. Weak in his father’s presence, Ryan blushed.

“Not everyone can be as holy and important as you,” quipped Jo. “I’ll go light the grill,” she said, winking at me through the porch door.

“I’m only kidding,” called Fred. “So, Sarah, what do you write?”

“Mostly poems,” I said.

“Poems,” he repeated. “About what?”

“About sex,” I said. “And destruction.” I knew I was pushing it—but I didn’t see the need to conceal my identity for Ryan’s dad. Weren’t we adults?

Fred paused before tearing through butcher’s paper to a stack of bratwurst. “Oh, really?” he said. “Ryan never mentioned that.”

*

After dinner, we followed the dirt roads to a nearby general store and purchased ice cream from an old man. We languidly sauntered back home, digging into our mint chip with wooden spoons. Cicadas moaning. We’d packed the Southern swelter and brought it with us, Fred quipped. I remembered the semen on Ryan’s windshield and laughed to myself.

“What do you do around here?” I asked Fred.

“Not much to do. But I’ve got this house, and I’ve got Jo. And the congregation. And houseguests like you and Ryan coming through. Life is good here.”

He prattled off specifics about the town population, its historic buildings, and proximity to Boston. Did Ryan and I want to go to Boston?

“Yes!” we both cried.

“We’ll head out tomorrow, then,” Fred decreed.

I’d wondered about our sleeping arrangements, certain Fred wouldn’t have us shacking up in sin under his religious roof. I was right. My second-floor bedroom neighbored Ryan’s separate sleeping quarters. The rooms connected by an old wooden door outfitted with a finicky brass lock. “This won’t unlock,” Fred had told me after placing my suitcase on the creaky bed, and I took his words as a personal affront. Had he assumed I’d attempt to sneak into his son’s room? He was right, of course.

I put on my pajamas and whispered to Ryan through the door: “This is bullshit.”

“It’s just a few days,” he replied. “Don’t do anything crazy, Sarah. Please.”

*

Jo stayed behind while Fred drove us into Boston, and in the car we listened to a Nuggets box set of sixties and seventies psychedelic rock that Ryan had picked up in a Durham record store. I sat quietly in the backseat, watching the world whir by while Ryan and Fred did all the talking, the father-and-son catch-up. I wanted to shrink, to disappear, feeling like the druggy interloper in an unaired episode of The Brady Bunch .

In the city, we walked through the Commons and strolled down Newbury Street, popping into stores we didn’t yet have in North Carolina. I bought skirts and jewelry and sandals while Ryan bought a new pair of sneakers that made me cringe. His lack of fashion sense was the one thing about him I could never quite overlook. I bought the majority of my clothes secondhand, from thrift shops and yard sales, and on these shopping sojourns I’d started to drag Ryan along, coaxing him into buying a vintage T-shirt of the hair band Warrant, a threadbare Harlem Globetrotters shirt, and later claiming a flannel-lined Dickies work jacket for him from the trunk of my brother’s car.

As we shopped, as Ryan acquiesced to my every whim, I could sense Fred’s patience narrowing. I became convinced that he disliked me. When Ryan slid into a café bathroom, his father and I dawdled together on the street corner, and out of nowhere he turned to me and said, “I haven’t seen Ryan in a long time, Sarah. And this is my quality time with him.”

“Okay,” I managed to mutter and turned away, my face burning.

When Ryan pointed out other stores along Newbury Street that he thought I might enjoy, I told him I was done shopping for the day.

That night, we grilled burgers on the porch of Fred’s brother’s home in ritzy Beacon Hill, which he shared with his wife and their daughters. It was a small apartment, but the nicest one I’d ever seen, with plush white furniture and gold-plated decor. I remained quiet, friendly but withdrawn, wishing Ryan had never invited me along in the first place.

Fred drove us home in the darkness and later, unable to sleep in the swelter of Fred’s old home, and hearing Ryan tinkering away in a room over—so close but so far—I rifled through my purse and found a bobby pin. I plied the bobby pin open and used it to jimmy the lock and, ta-da , the door swung open. Fred had been wrong, it turns out, or maybe he’d lied about the lock.

“Oh, my god,” Ryan groaned and I shushed him, crawling on top of him and running my hand underneath his shirt to his hairy chest. He was hairy everywhere—his back, butt, shoulders—and I found it oddly appealing, his unexpected hirsuteness in such sharp contrast to his book smarts and clean-cut Duke pedigree.

Ryan wouldn’t have sex with me, but I lay on top of him and pressed my ear to his chest, and it was just enough to feel as though I’d hoodwinked Fred.

Fred drove us to Cape Cod the next afternoon, and we drank lemonade and rented a boat. I had no idea where I was. I’d heard of Cape Cod, but it didn’t register as elite or expensive, just as a cape , although I had no idea what a cape was, either.

But Fred was feeling affable. After the boat ride, we veered into the Cape Cod Potato Chip plant where, in the gift shop, I watched Fred goad Ryan into purchasing a T-shirt as a souvenir. He held up a size extra-large to Ryan’s lanky frame and Ryan looked at me for approval, then back to Fred, and I quickly looked away.

“What do you think of the shirt?” Ryan called.

I turned and looked and shrugged. “I don’t think you’re an extra large?” I offered, avoiding eye contact with Fred, who hadn’t moved, who was as unmovable as a rock.

“Right,” he said, nodding. “I think I’m more of a medium, Dad?”

We headed back into Rhode Island as afternoon faded, stopping into Newport, where Fred’s other brother lived with his wife and no kids. Brad and Norah were younger and much more fun, waving us into their cute home outfitted with vintage tchotchkes, a record collection, and Morphine and Pavement CDs scattered around their kitchen counter boombox. They’d relocated from Virginia, where they’d taught business and finance classes at Virginia Tech, and where Brad had been involved in Roanoke Island’s Lost Colony outdoor drama program. Brad and Norah loved me without hesitation, and for the first time on the trip I felt comfortable.

It was getting late and I supposed we might stay the night, but Fred was dogged in his quest to usher us back home, back to our chaste bedchambers that he lorded over like an unimpeachable beacon of God.

*

On Sunday, the morning of Fred’s service, I wandered downstairs for breakfast, pausing to look at a book, maybe, or a painting, idling long enough to overhear one of his more informal sermons emanating from the kitchen.

“Ryan,” he was saying, “some girls are for marrying, and some girls are for fucking.”

I froze. I knew which category I belonged to.

Ryan and I had talked about marriage. We were impossibly young and it was all premature and a terrible idea, but even then I knew that marrying Ryan was the only chance I’d have at a steady, normal life—the kind of life that might feature a blue ranch-style house in a decent enough city like Raleigh or Richmond, and where I’d soon enough be pregnant with a son whose name we’d fight over. Then, shortly before his fifth birthday, the whole operation would go to hell because of Ryan’s subtle jabs about my parenting style, which would allude to my own troubled upbringing, something we’d later name irreconcilable differences . He’d eventually take up with the copywriter at his work, a petite bookish thing with a name like Jen or Lauren, who listened to contemporary country music while zipping around in her reliable compact car, and every other weekend I’d drop off our kid and spend the weekend with a drummer named Neckbone who lived in a functional shanty along the coast.

I shuffled into the kitchen, smiling, so that no one might suspect I’d overheard. It was liberating, in a sense, to be seen as a real person, someone with flaws as opposed to the pixie nymphet filter Ryan saw me in. But I was also wounded. I wasn’t perfect, but I believed I was a good person and good enough for Ryan. Why didn’t his father?

We attended Fred’s service and I said nothing about his comments to Ryan. I knew he would expect me to rage around like a cyclone, to hold this piece of information against him. But I also already knew we hailed from different planets; it was that fact that served as the biggest turn-on for us both. We had great sex because of it. Ryan was the first partner who’d ever given me an orgasm. He’s still the only man I’ve let shower with me. I felt unnaturally comfortable with Ryan, likely because I could seemingly do no wrong in his eyes.

We returned to North Carolina and I kept Fred’s words buried. I saw no need to stir up familial strife. Summer was only half over, and Ryan was out of the dorms at Duke and into his mother’s nearby home, a place where I could spend the night with as much frequency as I wanted. He worked an ongoing summer gig announcing games for the Durham Bulls, and when he was off, he’d drive the distance to Greensboro, where I lived with a friend. Between our back-and-forthing, it never felt like a long-distance relationship. We’d see shows two to three nights a week: Andrew WK, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Les Savy Fav, Bright Eyes, the Shins, Oneida. We’d go to dance nights at bars, and attend friends’ cookouts and parties. It was easy. So easy. But for me there was always a ticking, a gentle knowledge that an expiration date loomed. He saw it too. He had to have seen it. Everyone could see it, starting with his father.

Towards the end, I took up smoking again. I took up everything again. For a while, Ryan proved lenient. Maybe he enjoyed my testing the limits of our differences. But after a while, it was obvious my behavior chagrined him. We never really fought so much as we became exhausted of each other. The things Ryan once loved about me were mushrooming into burdens, red flags in his squeaky-clean world, and without his unwavering worship, my interest in him also waned. I finally broke it off on my birthday because Ryan was insisting I drive to Durham, instead of him coming to Greensboro, for celebrations. A small infraction, but this tug-of-war over our directions in life struck me as symbolic, so I seized the moment.

And I was truly angry, interpreting his lapse in devotion for never really loving me. I cried and he cried. “As long as you live,” I told him, “you will never find another woman like me.”

It was dramatic and aimed to hurt him, but I believed what I was saying. In the tearful phone calls where he begged me back, he repeated what we both wanted to hear: “There’s no one like you, Sarah. And you’re right—there’ll never be anyone like you.” I didn’t take him back.

*

I saw Ryan one more time. A month after my father gave up a long battle with his health, Ryan turned up on my front porch. It had been two years since our breakup. He was traveling through town with the Durham Bulls and wanted to buy me dinner, to tell me how sorry he was about my father, and how much he appreciated knowing him for the short amount of time that he did.

We drank a few cans of shitty beer and attempted clumsy sex in the dark, until I wanted Ryan to stop. It pained me that I was no longer attracted to him. It felt so foreign and eerie to be standing outside of the roles we’d once established. One minute I’d been washing dishes, the next I was opening my door to a ghost from my past. Only Ryan wasn’t scary. He was the most decent man I knew, and maybe I didn’t yet love myself enough to realize I wanted or deserved a decent man. Maybe I was just young. And narcissistic. And stunned. I ushered Ryan out of my house in the middle of the night to drive the route home and away from me one final time.

And that’s how most people disappear from our lives: with little fanfare. Nearly fifteen years since Ryan, I still consider our relationship the most normal relationship I’ve ever had. His name rarely comes up now when I’m chatting at parties or with friends, but that’s because there’s no lingering hostility or trauma to process. No need to jeer his name into the night sky. Like a seasonal sno-cone stand, we folded up shop and moved on.

Ryan finished Duke and worked in healthcare; he lived in Chicago for a while, and then married a doctor. He became a stay-at-home dad after the birth of two sons and lives in North Carolina. After college I moved, of all places, to Boston. I never forgot what Fred said about me—this religious and patriarchal pitting of sex and matrimony as opposing forces instead of pieces of the same pie. But Fred wasn’t the only person to think this, nor the last. I’ve become fluent in the ways female sexuality scares men. Since Ryan, I’ve loved—or believed that I’ve loved—a sea of grifters and drifters of all ages and professions, each fucked up and memorable. They were men who made me happy, for a time; men certainly better-suited for my temperament and lifestyle than Ryan. Still I found myself wishing sometimes that they’d all been a little more like him, all of them: from the men I saw no future with, to the ones I’d believed I’d marry but never did.