Don’t Write Alone Columns

The Poetry of Comics: A Conversation With Johnny Damm, Author of ‘The Science of Things Familiar’

“I’m a writer who uses a scanner, an X-Acto knife, and the library.”

This is “The Poetry of Comics,” a series of conversations with artists working at the intersection of comics and poetry.

For the second installment of this series, I interviewed Johnny Damm, author of The Science of Things Familiar . It is difficult to define Damm’s work; every classifier fits too tight, incapable of containing the breadth and originality of his style. Maybe it is most accurate to describe his art literally: collages of vintage comic book pages, depression era photographs, antique textbook diagrams, found postcard correspondence, historical interviews, archival research, and personal experience. These unexpected parts form a whole that is both emotionally intimate and culturally critical.

As the title suggests, The Science of Things Familiar dissects what we think we know, from the subtext of a romantic relationship to how white supremacist ideology underpins American music genres. Across these varied themes, there is poetry — not only in Damm’s language, but in the tension he creates between word and image.

During our conversation, Damm and I spoke about his process, the history of poetic comics, failure’s radical possibilities, and his new book, Failure Biographies , out this month through The Operating System .

*

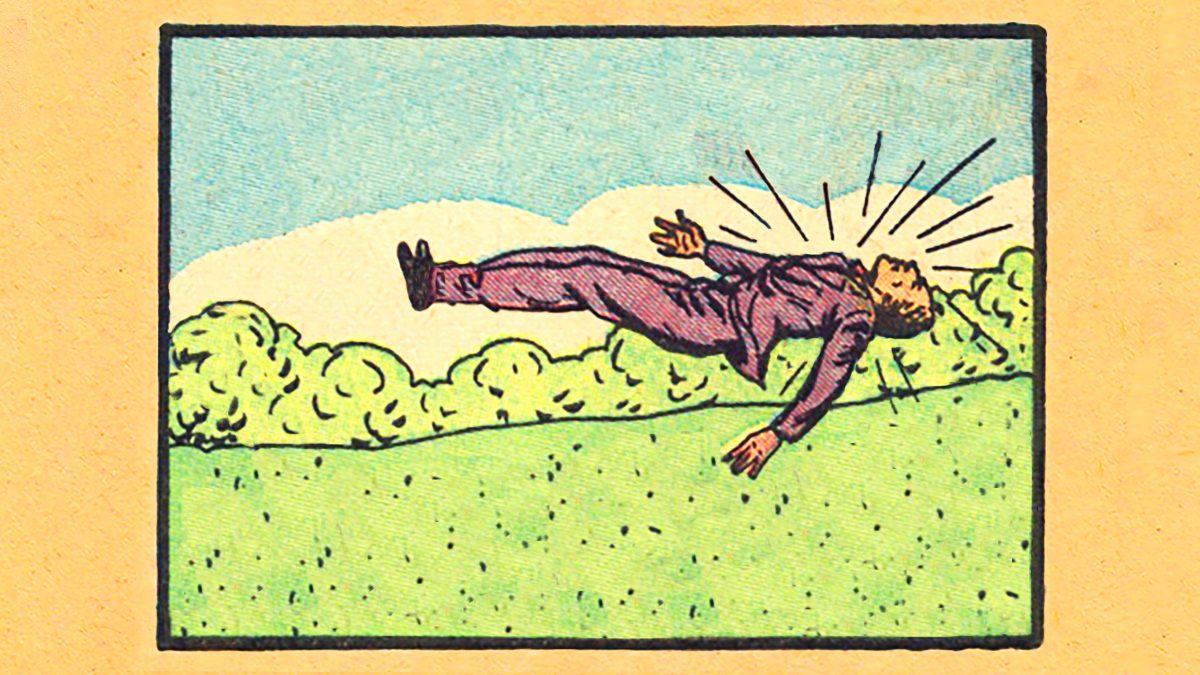

From the “Bodies In Space” series in Failure Biographies

Eliza Harris: How do you see your work relating to the genre of “comics poetry” or “poetry comics,” which are both phrases that have been gaining popularity to describe the intersection of these genres?

Johnny Damm: The Science of Things Familiar is funny because when I was originally trying to write that book, for the life of me I was trying to write a novel. And, of course, when it got picked up by the publisher The Operating System, they immediately said, “This is great poetry.” I think I’d been specifically avoiding poetry comics as a field, and after that I had to grapple with it.

I don’t know if poetry comics is the most useful terminology. I’ve always thought that the need to establish a specific genealogy for poetry comics, separate from comics, is a misplaced energy. There has always been a lyric and poetic impulse in comics. There’s always been nonnarrative comics. My interest has been in going back and looking at the history of comics and the way that comics have functioned as poetry.

If you’re paying attention to what’s been going on in independent comics and mini comics, really if you go back to early comic strips like George Herriman’s Krazy Kat or the first fifteen years of Charles Schulz’s Peanuts , those comics function so poetically. In early Peanuts , Schulz made four-panel comics that really mimicked the movement of a poem. He would often make a turn in his second-to-last panel that is very similar to what, in sonnets, we call the volta. So I feel like it’s just important for people getting into comics poetry and calling it comics poetry to think critically about how these genres come about and to see all the people working on the margins of comics who are doing similar things.

EH: I love how the meaning of your visuals and the meaning of your words both resonate and sabotage each other . Could you talk about your process of bringing text and image together?

JD: I’m not creating the images, and actually, increasingly, I don’t create the text. With my newer work, I scan old comics pages from the early fifties and forties, reprint them on my printer, cut everything out from the page, and then refill it in. There are these great early comics called Planet Comics that follow very little of what we now think of as comics conventions. For three years, I’ve been using their panel layout and filling it in with old, depression-era WPA photographs. A lot of my time is also spent researching to find text from interviews and other sources. So I’d say that in the larger sense, I’m a collage artist, or I’m a writer who uses a scanner, an X-Acto knife, and the library.

Page from “Compton’s Cafeteria, 1966” for Guernica

EH: I admire the range of sources you draw from for your text. From “Hello Betty,” which adapts one family’s postcard correspondence into a horror comic, to “ Compton’s Cafeteria, 1966,” which i ncludes the words of participants in that influential San Francisco riot. Can you speak about building work around found dialogue? What draws you to work with it?

JD: Ever since I finished Failure Biographies , I haven’t put my own words in a single comic. I decided I’m going to try to only use other people’s words. My work is interested in the idea of counter-histories, of histories we don’t pay enough attention to. I want to reveal those histories while letting people speak for themselves. For instance, the Compton’s Cafeteria riot is a hugely important piece of history, but I shouldn’t be the one to tell that story—instead I’m trying to get people to listen to the voices of people who were there.

I think what often gets people to notice lesser-known histories is putting them in a new context and a new form. To go back to poetry, it’s Emily Dickinson’s “Tell all the truth but tell it slant.” We have endless information at our fingertips, but that’s not what actually gets through to us. Dickinson says poetry can approach at an angle, dazzling gradually without blinding us, and I look at comics in a similar way. For me, comics provide that slant that hopefully gets people to see history how I see it and how the people I admire see it.

“ There has always been a lyric and poetic impulse in comics. There’s always been nonnarrative comics. ”

EH: Your new book, Failure Biographies , uses comics collage to tell the stories of failed twentieth-century artists. You spoke earlier about how “failing” at writing a novel is part of what led you to the kind of work you make now. I’m interested in how you define failure for this forthcoming book and why you want to tell these stories of “failure.”

JD: Wow, yeah. I actually didn’t even think about the fact that I failed [laughter]. No, you’re right, it was a failure, and that is part of my interest. I’m fascinated by people who fail on their own terms. I went back and I read a book by Jack Halberstam called The Queer Art of Failure that talks about failure as productive and anti-capitalist. The idea of there being something radical about failure set me off.

For Failure Biographies , I looked at three forms of failure. The first was systemic failure, people for whom systems destroyed their career. I researched women filmmakers who pioneered early silent films and then got pushed out of the industry. Then I looked at the category of what I think of as “productive failure,” where people made something else out of the thing they failed to do. Marta Minujín is an Argentinian artist who tried to do this wild installation covering the Statue of Liberty with hamburgers that, of course, wasn’t allowed to be done, but she documented the process. And so failing became the artwork. Lastly, I’m really interested in the political failure of art, when artists have given up on art because they were trying to use art as a political force to change the world and basically weren’t able to. Benjamin Patterson and Noah Purifoy are the artists I talk about with that form of failure.

Page from The Science of Things Familiar

EH: In your first book, The Science of Things Familiar , you have what I’m going to call diagram poems. They’re schematics paired with one or two lines of text. These diagram poems feel both very personal and universal—experiences we’ve all had of deceit, lost days, things unsaid. Could you speak about your diagram poems a bit, about how they came about or what they came out of?

JD: For that series, I had this idea that I was going to make one diagram a day. Turned out that was way too ambitious, because they were actually kind of hard [laughter]. I used diagrams from nineteenth-century scientific textbooks and manuals and kept them basically how they originally appeared, but I added a title to each that traces a domestic relationship between two people.

I’m not usually a personal writer. That is actually my most autobiographical work. I think they had an effect on me, because once I was done with them I’ve never been able to do that again. I could not do another diagram work now.

EH: Are there people working at the intersection of visual art and poetry that have influenced you?

JD: I’d say the handful of people who make collage comics really gave me permission to make comics. Most notably, Jess , who was the partner of the poet Robert Duncan. Also Max Ernst, whose collage books we now definitely see in the lineage of comics.

For more contemporary work, I love the artists being published in the Visual Poetry Series by Pleiades. The last few issues of Ink Brick: a Journal of Comics Poetry were just great. I’ve been following them since they started and I love what they do. One of my favorite books in the last year was Lale Westvind’s Grip . It’s a wordless comic that operates under this kind of dream logic that seems to me more lyric than narrative. Manga artist Shigeru Mizuki’s Kitaro is fabulous and has influenced my approach to the page. His work has these incredibly elaborate, photo-realistic backgrounds with these very crude comic figures in front. R. Sikoryak made a book a few years ago where he took that Apple agreement that you have to click on if using an Apple product, the thing that everybody skips over, and made it into a comic. That’s been very useful for me to think about because, to go back to Dickinson’s “tell it slant” idea, how do we get people to read this thing that they were not going to read?

There’s a lot of great people I read who have nothing to do with poetry or visual arts who are really essential to my thinking about how I present other people’s words and how I present histories. Books like Howard Zinn’s A People’s History and Robin D. G. Kelley’s Freedom Dreams .

EH: Finally, where can readers find your first book, The Science of Things Familiar, and preorder your new book, Failure Biographies ?

JD: The Science of Things Familiar and Failure Biographies can both be ordered on The Operating System’s website. The Operating System has also created an open-source library so that all of their texts are accessible as a PDF for free.

![This comic show a person throwing a watch against a brick wall interspersed with text. The text reads, "[The riot] / was a natural thing / for people to do."](https://s37710.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2024/03/Damm_Comptons_8_200dpi_1625868137.jpg?1625868137)