People Fans

Love in the Age of Prince

“After hearing ‘1999,’ I wouldn’t date any woman that wasn’t down with Prince.”

In August, 1982, two months before the release of Prince’s electro-pop-soul masterwork 1999 , my best friend Jerry Rodriguez and I watched the performance clip of the album’s self-titled first single when it played on the thirty-foot video screen at our favorite nightspot, the Ritz. Clad in a dark vintage suit and white sneakers, I was a nineteen-year-old college student at Long Island University who spent more time prowling darkened clubs than studying. After becoming boys, Jerry and I would take the D train into the city from his Brooklyn apartment where we usually ended up at the Ritz with its five-dollar cover charge, ear-blowing sound system, and cheap drinks.

Buzzed on Long Island iced teas, my jerky dance movements came to a sudden halt when I heard keyboard chords bubbling. Turning around, I stared in stunned awe at the spectacle projected on the screen. Wearing a flowing purple coat and high-heeled boots, Prince resembled a futurist Dr. Strange steppin’ through time and space to warn us mere mortals of the forthcoming apocalypse that would happen in 1999. “I was dreamin’ when I wrote this, forgive me if it goes astray,” he sang, “but when I woke up this morning I could have sworn it was judgment day.”

For the next few minutes, sonically tripping, head nodding to the future shock blaring through the speakers. Musically, Prince made a song that was, at least to me, the best new wave and best funk single of that year. Lyrically, he laughed in the face of Armageddon while shaking his ass until the dawn. As the world was being ravished by nuclear annihilation, Prince was just getting the party started.

When 1999 was finally released in October, I bought the album at Disc-O-Mat in midtown and ditched school for the rest of the day. Hurrying back home to Harlem, I bought a sack of chucky black and retired to the bedroom for the rest of the day. After sliding out the glossy picture sleeves (on one he looked like a black Bowie, while the other was a semi-nude shot of Prince in bed with watercolor paints and a blank page), and for the remainder of the day, I toked reefer and played records.

From the opening party at ground zero and the robotic voice of God declaring, “Don’t worry, I won’t hurt you, I only want to have some fun” to the smoldering ballad “International Lover” that closes the over-an-hour-long aural experience, the album was prophetic (“1999”), hedonistic (“Let’s Pretend We’re Married”), spiritual (“Free”), sexy (“Little Red Corvette”), and sinister (“Something in the Water”), and collectively visionary.

To this day, 1999 remains my personal favorite Prince album, winning over Purple Rain or Sign O’ the Times . 1999 took me from mere fandom to the deepest love for the man and his art. A maverick musician who was constantly topping himself, making me “ponder the mystery of human greatness,” as Ralph Ellison once wrote. After hearing 1999 , I wouldn’t date any woman that wasn’t down with Prince.

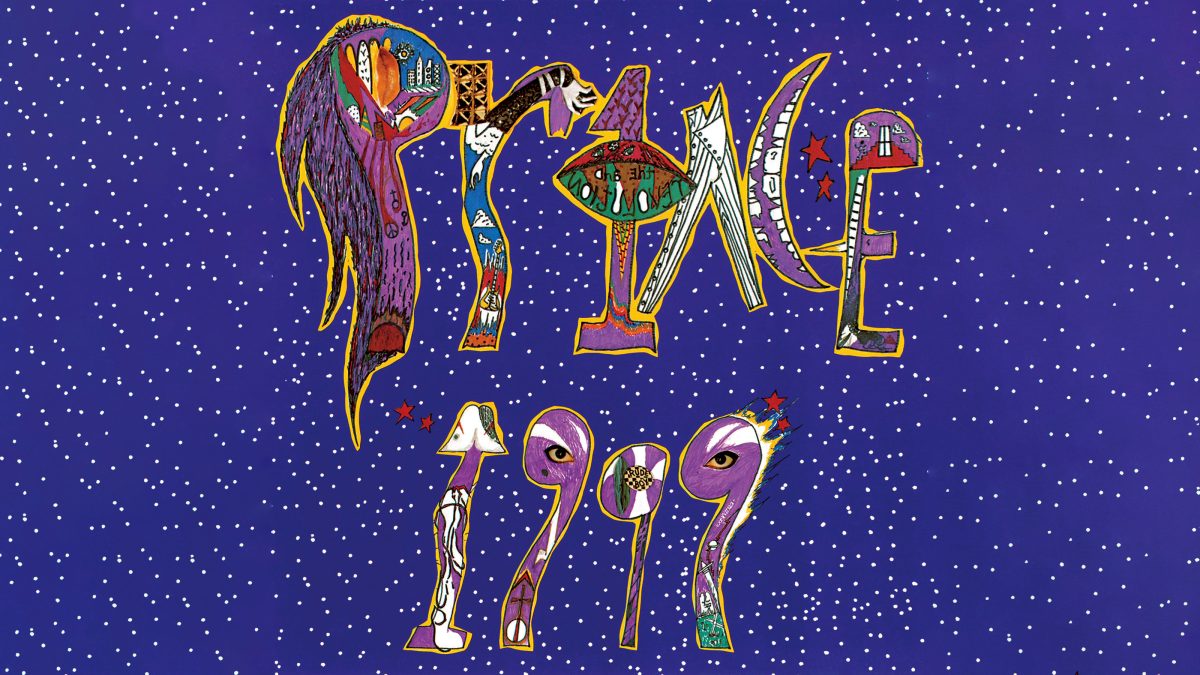

While the album played again and again, I lay on the blue-sheeted bed studying the bizarro album art. Gazing at the striking purple cover for what felt like forever. Prince’s name and the album’s title were scrawled in graffiti-style crudeness that resembled boys’ bathroom drawings and the weirdness of Pedro Bell’s cartoon designs for P-Funk albums. Stoned from the weed, my red eyes constantly returned to the title 1999.

Playing a silly game with myself, I calculated that in 1999 I would be thirty-six years old, which to my then-nineteen-year-old self sounded ancient, dusty as an old record. If I’d had access to a crystal ball, what exactly would I see in my future? Would I be a famous novelist chatting with Dick Cavett on PBS? Would I be married to my college girlfriend Denise and living in Long Island with our badass kids? Or who knows, maybe Prince was on some Nostradamus shit and the sky really was going to turn purple, followed by destruction.

In the real 1999, while the planet didn’t perish that year, for me and the small world I inhabited, it all came to a screeching halt on August 3rd, two months after my thirty-sixth birthday, when I was riding in the back of the ambulance with my long-time girlfriend Lesley Pitts. Lying on a gurney, she was being rushed from our first-floor Chelsea apartment on 22nd Street to St. Vincent’s Hospital, after she complained of a headache and shortness of breath. Leaning over her, I grunted something reassuring.

A reader in more ways than one, Lesley was a fan of the literary sarcastic sisterhood (Dorothy Parker, Fran Lebowitz) and from the day we met she was never one to bite her tongue. Looking at me, she said, “You know this shit isn’t fair, right?”

“What are you talking about?”

“Well, you’re the one who likes to hang out all night and do drugs, why am I the one laying in the back of an ambulance dying?” Lesley was a publicist, a profession that often leads to exaggeration. In the eight years we’d been together, I’d heard more than a few exaggerations and thought that her speculation of death was simply another.

A few hours before, we’d been in the spare bedroom that I used as an office, making out like horny teenagers while listening to an advance of Me’shell Ndegeocello’s upcoming Bitter album. A few hours before, she kissed me wildly, madly, and then asked if I had any intention, after all those years together, of ever marrying her. “Of course,” I said, knowing that was the correct reply.

Lesley was three years younger than me. When we first started dating eight years before, she was opposed to getting married, having kids, taking the subway, and living in Brooklyn, but people change and so do their needs. A few hours before, we’d been making plans for the future.

“You’re not dying,” I said as though I knew something. I knew nothing.

*

In August of 1991, on a different summer afternoon, Lesley and I met by chance when my then-writing partner Havelock Nelson and I left a meeting at Random House, whose music books division Harmony was publishing our book Bring the Noise: A Guide to Rap Music and Hip-Hop Culture . Although the term “hip-hop writer” wasn’t really in use yet, both Havelock and I wrote about rap music for various publications. While our book was slated for release three months later, the meeting was to talk about the book party Random House was refusing to pay for.

Afterwards, we drifted down Lexington Avenue, sweating through our button-down shirts and grumbling about the cheapness of corporations. Since we both needed somewhere air-conditioned to chill for a few hours, we decided to head to Set to Run, whose offices were on the thirty-first floor of a deco skyscraper on 42nd Street, across from the Chrysler Building. The publicity firm handled press for most of the major labels including Def Jam, Delicious Vinyl, and Tommy Boy.

Employing mostly women on staff who were smart and beautiful and cool as hell, they usually had new music straight from the studio blaring in the offices. If lucky, you might see Q-Tip on the elevator, KRS-1 chilling in the conference room, or Chuck D meeting with his publicist. I accidently stumbled into Lesley’s office when I’d stopped to speak to another young woman whose office was next door.

In previous visits, the space was occupied by a cranky woman who I barely remember, but that particular day when I glanced inside, I noticed the most beautiful girl in the world, a full-figured, caramel-skinned woman with curly hair and a majestic smile that she coyly flashed when she caught me staring. Having grown out of my shyness years before, I boldly walked to the front of her desk and introduced myself. The perfumed air around her desk was rousing as I admired the sun reflecting off her metal earrings.

“I know your name from the press list,” she said, her voice strong and lipstick perfect. “I’m Lesley Pitts.” After shaking hands, she explained that she’d just started at STR a few months before. “I’m working with 3rd Bass and a new group called Downtown Science.” Opening her desk drawer, Lesley found the advance cassettes for both projects and handed them to me along with her business card. But, instead of leaving, I pulled up a chair and Lesley pulled out a Newport; we both smoked the same brand. She offered me the pack and when I opened it, I noticed one of the cigarettes was turned upside down.

“What’s that all about?” I wondered.

“That’s the lucky cigarette,” Lesley answered.

“What’s so lucky about it?”

“I haven’t figured that out yet,” she said and we both laughed. In the midst of our conversation, Lesley told me about growing up in Irvington, New Jersey and partying at the infamous Club Zanzibar in the ’80s. “Did they play a lot of Prince there?” I asked, and Lesley laughed. “They played some; hell, it was the ’80s, everybody was playing Prince.”

I asked, “So what’s your favorite Prince song?”

Looking up as though realizing she was being challenged, Lesley replied, “I love Prince’s music, but I suppose, at least for today, I’ll say my favorite is ‘How Come U Don’t Call Me Anymore?’ Do you know that one?”

“Of course I know,” I said, “it’s the B-side of ‘1999.’”

“Yeah, but do you know the Stephanie Mills version?” Now it was my turn to laugh, because obviously my Prince test was being put back on me.

“I never owned it, but I used to play it in a jukebox at a bar uptown.”

“I guess that’s good enough,” she replied. Jesus, I thought, not only was she fine as peach wine, but she knows about Prince B-sides and the people that covered them. Minutes later, when it was time for me to leave, I told her I’d be happy to interview her clients Downtown Science and would call her the following day.

“Well, they’re opening for 3rd Bass at the Beacon next week. Maybe you can come.”

I called her the next day and the next day and the day after that until the night of the show. Lesley giving me one ticket for the concert seemed kind of strange, but when she instructed me to meet her afterwards, I realized her intentions. After the show, I waited a little over an hour on the police-and-b-boy crowded street for Lesley to finally emerge from the exit. Although she was only 5’ 4 her provocative olive green Charles Jourdan pumps gave her another few inches.

“Do you want to go have a drink or dinner?” she asked. Looking at my watch, it was quarter to twelve.

“Wherever we go we have to get there before midnight or else I’ll turn into a cockroach,” I said, though to this day I don’t know why.

“If you turn into a cockroach, do you still make Kafka references after midnight?” It was at that moment that I knew I was in love.

Two days later, on a Sunday evening, I went to her Brooklyn studio apartment in Fort Greene for dinner. As Al Green sang in the background, we talked a lot about books (Flannery O’Connor and Katherine Dunn were her favorites) and writing. Much later, I’d discover that, before becoming a publicist, she too once dreamt of being a writer or editor, and would constantly preach to me from the bible of Strunk & White. That night, the sky exploded and a heavy (purple) rain fell for hours. “You don’t have to leave if you don’t want to,” she said as the drops splashed against her window. Taking it slow, we pulled each other close for the first time and fucked until the dawn. While I hadn’t had a serious girlfriend in two years, I had a feeling that was about to change.

The following week, I somehow broke my foot in a drunken tequila shot accident at my favorite bar, Night Birds. Returning from the hospital with crutches and a cast covering my leg, Lesley looked at me and shook her head. “I’ll never get rid of you now,” she said and laughed.

*

With Lesley working as a music publicist and me as a music journalist, we had more than our share of CDs and cassettes in the crib. Although our tastes varied, we always agreed on the genius of Prince, whom we played often. The following October, when we moved to Chelsea, Prince’s Love Symbol album came out. Although we hadn’t bought beds yet, we slept on the floor making love as “Damn U” played on repeat through the night.

The apartment was small and dark, but we both loved living in the middle of Manhattan. That first year, Lesley and I bonded over a mutual love of films, cartoons (especially The Simpsons ), books, restaurants, vacations, and cocktails. Lesley, whose daddy was a hard-drinking barber from Newark, might’ve held her liquor better, but we both had a tendency to party a little too hard in those early years. After watching a Thin Man series on TCM, we christened ourselves Nick and Nora; as in the movies, it was me (Nick) that was usually the drunk one.

On July 14, 1994, Prince played a benefit concert at the Palladium seven days after Lesley’s twenty-eighth birthday. Her friend Karen Lee, who was Prince’s publicist, got us tickets. After the superb show, Karen somehow found us in the crowd and offered to take us into the Michael Todd Room upstairs where the after-party was happening.

“Would you like to meet him?” Karen asked. During that period, Prince had replaced his name with a symbol and even his employees didn’t call him Prince.

“Of course,” Lesley and I both screamed; later I would compare our crazy fan behavior with the girls we see losing their minds in those Beatles newsreels. The wait seemed to take forever as we stood outside the VIP area, where we could see him sitting next to his friends Lenny Kravitz and Vernon Reid, both of whom had joined him on stage to perform “Mary Don’t You Weep” and “None Of Your Business.”

Finally, Karen escorted him over. Prince was dressed in flowing white Versace and sucking on a red lollipop. Lesley, who was beaming, put her hands together and bowed. Prince took the sucker out of his mouth and started cracking up as we all did. Later on I asked her, “What was up with your praying hands?”

“Oh be quiet, I didn’t even know what I was doing.”

I wish I could say our relationship was always as magical as that night. Lesley was a wonderful woman who encouraged and often edited my work, but I was in my early thirties and coming into my own as a writer, publishing steadily in the pages of The Source , Vibe , and XXL while believing the myth that in order to be a great scribe, one had to drink to excess, be as selfish as possible, and only live by your own rules, which usually involved partying in Harlem bars, sniffing bad coke, and fucking around as though it was my right. Too much Bukowski can be a bad thing.

While Lesley was home becoming more domestic, cooking elaborate meals and redecorating with fervor, I was running the streets believing that the debauchery would soon transform me into a literary genius. Lesley, who had a tongue that was sharp as a razor, argued with me, screamed at me, locked me out, and, sometimes I’m sure, cried herself to sleep worrying about my trifling ass.

“I guess you know me well, I don’t like winter, but I seem to get a kick out of doing you cold,” Prince once sang on the aptly named “Strange Relationship.”

During this time, Lesley worked at various labels including Jive, LaFace, and Loose Cannon (among her clients were TLC, R. Kelly, Toni Braxton, and Buju Banton), but in 1997, she formed her own company. After debating about the name, (“Maybe I should call it Pig Fuck,” she said snidely) the company was called No Screaming Media. One afternoon, not long after setting up shop, Lesley called me excited from her SoHo office. “You’ll never guess who I’m going to do press for?” Somehow with three guesses, I still failed.

“Wrong. Prince. I’m going to be working with Prince.”

Having been released from his Warner Brothers contract, Prince formed NPG Records, which released his new project as well as discs by Chaka Khan and Larry Graham. Lesley put together their press junkets, television appearances, and, when Prince was in New York City, various after-party gigs when Prince and the band often played through the night.

One such event was at Tramp’s in September of ’98, when Prince played a late-night gig after his Madison Square Garden concert. Having skipped the concert, I’d gone to a party instead and arrived at the club already intoxicated. Lesley, standing at the door with her clipboard, took one look at me and said tersely, “Go home.” The next day she told me it was over between us. “I can’t take anymore,” she said, staring at me in a weird way.

“Why are you looking at me so strangely?”

“Because you just get stranger and stranger every day.”

Although I have no recollection of getting up from my chair, I do remember falling to my knees, crying like a baby, and begging her to forgive me. Remaining silent, Lesley walked toward the door and glared at me coldly. “The only way I’ll stay with you is if you go to therapy,” she said. “And don’t just say ‘yes’ and not do it. If you don’t have a therapist by Friday, I’m gone.”

*

Thankfully, Lesley stayed and 1999 was shaping up to be our best year together. I’d stopped most of my wicked ways and was waking up early every Monday morning to walk to the therapist’s office in Greenwich Village. For Valentine’s Day, we spent the weekend at a blaxploitation convention in Sleepy Hollow, hanging out with Fred Williamson and Antonio Fargas. In the spring, we went to a charming bed-and-breakfast on the Jersey Shore, and, for her thirty-third birthday, I took her on an old school disco cruise where B. T. Express performed.

Twenty-seven days later, after being rushed to the back of the hospital where the doctors were examining her, Lesley sat up a little and said, “Michael, do me a favor. Take my cell phone outside and call Miguel and tell him I won’t be able to make it to dinner.”

“What?”

“You heard me. Do it now.” Following directions, I went outside and made the call. Three minutes later, I walked back into the lobby as a short African-American priest walked toward me. He stood in front of me, glared in my eyes and said, “She didn’t make it.”

“I think you have the wrong person,” I replied.

With his cold priest fingers, he grabbed my hand. “I’m sorry, she didn’t make it.”

Lesley was right, and had sent me outside so I wouldn’t have to watch her die. Even in her last breath, she was thinking about me. A shiver went through my body as they led me to the room where her body lay after a pulmonary aneurysm.

The next few days was a slow-motion bad dream of funeral arrangements, dealing with her mother’s anger, looking for a new apartment, and trying not to throw myself in front of a zooming subway. The world felt as though it were made of quicksand. At home alone, I played a lot of Mary J. Blige and Prince, and even put a few of the lyrics to “The Beautiful Ones” on her funeral program.

A few weeks later I got a call from writer Quincy Troupe, who was editing a publication called Code . Apparently, it was decided that the December 1999 issue would have Prince on the cover.

“We want you to go down to Paisley Park Studios and interview him.”

“No thank you,” I replied. I’m sure he was surprised.

“Actually, they requested you.”

“For real?” A few days later, I was on a plane headed to Minnesota.

I arrived at Paisley Park by cab; outside, it was raining. After waiting for a half-hour, Prince not only blessed me with a personal tour of the facility, but he also gave me a ninety-minute interview. Talking to Prince wasn’t easy since he often talked in parables to press. However, when I inquired about the meaning behind “1999,” his answer was clear.

“I just kept having these dreams that something terrible was going to happen and the world might be a little scary.” Remaining silent, I nodded in recognition. Although neither of us mentioned Lesley, I felt as though Prince was speaking to me about her in his own coded language.

Sudden death can be haunting. Damn near twenty years after Lesley’s passing, I still think about her every day: hearing her reassuring voice and hearty laughter, remembering her quick wit and ready sarcasm, listening to her discerning advice and constantly playing soul music. There are still days when I just lay on the couch staring at the ceiling, but on most I’m at my desk writing with the creative confidence she instilled in me. Not long ago, I was talking to her old friend Sheila Jamison. She listened quietly as I rambled about ancient bad boyfriend guilt and the things I did wrong when Lesley was alive. Sheila looked at me and shook her head. “She loved you, Michael, and she knew that you loved her and that’s all that matters.”