Places Natives & Neighborhoods

An Experiment in the Village

“I was amused, but I also registered that my privacy had been invaded.”

I remember where I was when I realized the magazine experiment was a bad idea. Brand new to my Bushwick apartment, I was sitting in a chair facing two tall windows that for the first time in my eight years in New York had views unobstructed by safety bars. I now rented the entire ground floor of a row house, and the unprotected windows seemed unwise. I felt exposed. Accessible.

The man I was talking to on the phone—a stranger who had called to participate in my experiment—directed me to an online video he’d made of women riding in the back of his rickshaw. He ran the rickshaw around the Village in a superhero costume, hurtling himself off the sides of buildings as he carted female passengers to their destinations in wildly circuitous routes. The women in the video wore short skirts and bare legs. The camera was positioned below knee level. Every time he tipped them back so their long hair grazed the ground, their knees jostled apart and high heels kicked toward the sky. Trance music played over peals of laughter. He told me he was from Florida. He adjusted the mouthpiece so his lips nestled closer to the microphone.

“Do you like it?” he asked.

“Looks fun,” I said. Key words popped from the titles of dozens of clips he’d uploaded of women on his rides: “spanking,” “girls in shorts,” “quick lube,” “sexy girls,” and “major blow job,” referring to gusts of wind.

“So where do you live now?” I asked.

“Right now,” he said, “I don’t have anywhere to live. I live in Washington Square Park. Sometimes I meet a girl and stay with her . . . ”

He had such a gentle voice. I hadn’t experienced this kind of softness from a man unless his lips were touching my ear, but by then I’d know the weight of his body, the scent of his flesh, and the pleasant balance of hardness. The man was trying to break down our barriers. I got the sense he was trying to seduce me, or at least charm me, for reasons that were unclear. Perhaps it was manipulative. Perhaps he was trying to convince me that the videos were made with the women’s consent, which seemed unlikely.

My thighs were sweating. It was a July afternoon. The computer was propped on my legs, overheating, and the chair’s wool was scratchy against my skin. He pointed me to another video of him running the rickshaw, his lean body wrapped in blue Spandex. In the cover frame, the camera is trained on his ass.

“Why is this a picture of your butt?” I asked.

“There’s a picture of my butt because it’s a picture of a rickshaw,” he said.

Something about the way he said it made me think: Jail . I knew his name from his email address, so I googled him.

Right away I found it—a recent mug shot from Miami-Dade. He was glam rock and stringy-haired, pouting for the camera. I understood then that the way he worked his sex was second nature, and I couldn’t fault him for it. Base reflexes were often exhibited by those with little resources. His charges were light. I was sold on his black satin jacket.

Days before, I was moving out of the Village. I’d lived in a tiny rent-stabilized apartment on West 3rd Street for a couple of years, and in another rent-stabilized place in SoHo for six years before that. When a friend had announced that she was moving to Los Angeles, I had asked who was taking over her apartment. It was giant, just off the train in Bushwick, on the leafy border of Queens. “You are,” she said. Days later, I had a handshake lease with the Sicilian landlords who lived upstairs; the prospect of change excited me. I started dumping and donating items to lighten my load for the move.

In my final few hours, I was coming home from an errand. I stepped onto my block, past Ben’s Pizza and then Bleecker Bob’s record store, which has since closed. I lived upstairs. There was always so much activity. Men tossing pizza dough. The guy in dreadlocks selling bongs and pipes from a stool. The man in the leather jacket hawking comedy shows and thrusting flyers in faces. As I crossed in front of the guy on the stool, I saw something unusual on a card table that caught my eye: my name, on a mailing label, on a magazine displayed for sale.

Then I saw my name again and again. My name and my address were all over the table, on many mailing labels, dozens of them, in front of my apartment where the magazines had first been delivered, and where I had recently left them, in the receptacle in the hall, for recycling. Months’ worth of my New Yorker s, Harper’s , Elle s, and Dwell s that had once lived privately in my space were now spread out in the sunny public. They were no longer mine, but they still had the signature of my stuff.

“One dollar, only one dollar,” called a man from the ground. His back was against the wall, next to my front door. I’d seen him around. His legs were extended, feet dirty and bare, clothes tattered, probably drunk, I could tell by how he spoke.

“These are my magazines,” I said. I started pulling the labels off.

“One dollar, only one dollar,” he said.

I was amused, but I also registered that my privacy had been invaded. Had he gone through all of my garbage? I lived alone on the fourth floor on a busy stretch between MacDougal and Sixth Avenue, where crowds gathered at the basketball courts or outside the sketchy McDonald’s. Growing up in rural Michigan where everyone knew your business, I’d always loved being part of the big city’s blur, but suddenly I wondered if the joke was on me. Maybe everyone knew my name. Of course they didn’t. But I’m someone who doesn’t even wear sweatshirts with affiliations on them; I avoid emblazoned identifications. Had I known that my recycling was being sold for profit, I would’ve removed my name and address from the covers. I cherish anonymity, and it had been broken.

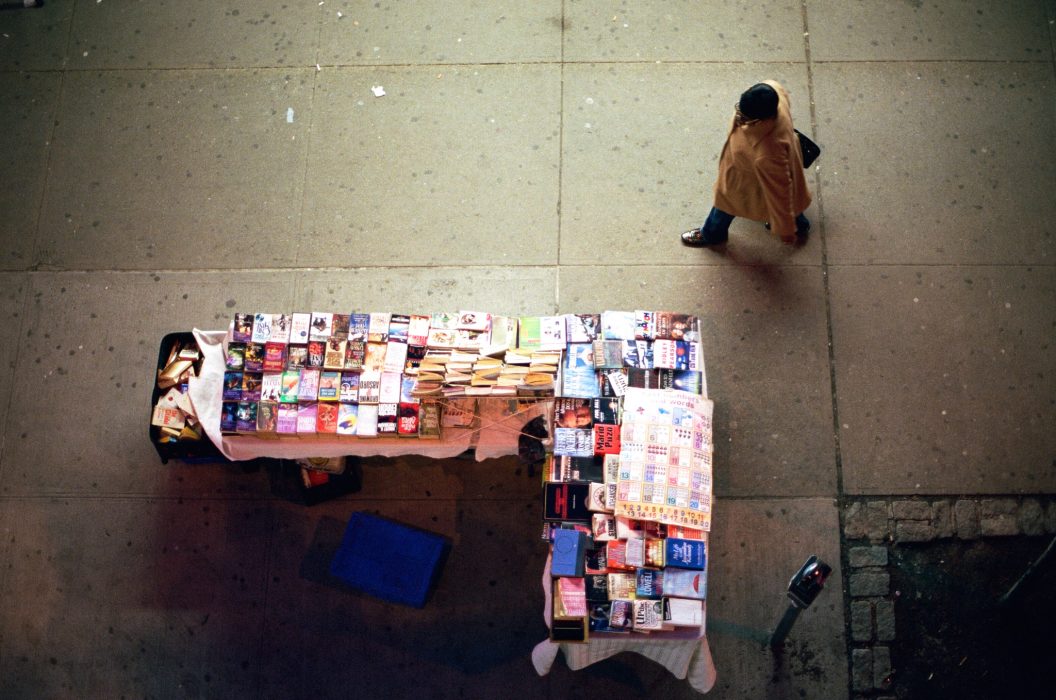

But I liked that I was contributing to a rogue economy I didn’t know existed. I couldn’t recall ever witnessing a transaction, not even outside my apartment, where the guy with dreadlocks sat all day on a stool and never seemed to talk to customers. Card tables were often set up around the Village with books and records for sale, but the few times I was lured in by titles, the vendors were so aggressive that I fled, wondering if the merch was stolen. Since I never bought items from street vendors, I couldn’t help but wonder: Who did?

I decided to conduct an experiment in which I would gather information from the customers and then study the circuitry of data based on interviews: where customers lived, why they were in the Village, whether they were tourists or locals—questions that would show a dimensional picture of a magazine’s life cycle. I’m entranced by data maps and visualization enabled by technology like sensors and tags, and I considered digitally chipping them, but because I didn’t have a clear idea of what I was looking for, I kept it simple.

Over the next few weeks, I would bring the vendor more magazines—mailing labels removed—with a typed note tucked inside that said: “If you bought this magazine, you are part of an experiment. Please email me to discuss: [my email address].” I may have called it an “experiment!”—exclamation point!—as I deliberated over the tone, uncertain of my audience. Uncertain, even, of what I was trying to learn.

But I was curious about the Village community. Ever since I’d moved there, I’d wondered if there was much of an authentic spirit left to it, if such a thing exists, or if it was all a tired, collective groping for the past, as evidenced by contrived theme bars and caricature open mics. Even at one of the best venues, a tagline on a Google Map reads, “Former haunt of famed poets & musicians,” with no mention of why you’d bother going there tonight. The Village felt nostalgic and transient, with an influx of over 5,500 NYU freshmen each year. Given the throngs of logo sweatshirts, I had a sense of who the students were, but who were the locals?

I’d witnessed a scattering years earlier, during the renovation of Father Demo Square. The triangular “square” on the west side of Sixth Avenue, bordered by Bleecker and Carmine, had been a run-down brick plaza populated mostly by pigeons and the characters who fed them. Outfitted with a couple of benches, one centered lamppost, and no fence, it was also a convenient shortcut that carved through the heart of scruffy urban activity. Locals sat for a minute to eat a slice of Joe’s Pizza; the homeless sprawled on the benches at night. Cutting through that plaza, I appreciated the dynamics of brief commingling and thought of Jane Jacobs when she wrote of city sidewalks: “Cities are full of people with whom . . . a certain degree of contact is useful or enjoyable; but you do not want them in your hair. And they do not want you in theirs either.”

Around 2005, the city began a $1.3 million renovation of Father Demo Square, opening in 2007 with a central tiered fountain, decorative tiles, and landscaping—all enclosed by a three-foot high spiked perimeter fence to keep out the homeless.

Ironic, I thought, that a square named in honor of a social activist was now unwelcome to the homeless. Father Antonio Demo (1870-1936) was the beloved pastor of Our Lady of Pompeii Church on Carmine Street. Born in Italy, he helped Village immigrants secure jobs. He was a missionary, raised funds for charities, and built a school for children. He is revered for his leadership and generosity during the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911, which killed 146 young women, mostly Italians and Jews. Acknowledging that grief spread beyond his Italian parishioners, Father Demo allowed the New York Women’s Trade Union League to distribute leaflets in Italian, Yiddish, and English. In 1997, forty years after his death, the Pope honored him as among the Blessed, one step below sainthood.

When I delivered the first batch of tagged magazines to the vendor, he was sprawled on the ground with a bottle in his hand. He didn’t understand that I had a donation, as I selfishly framed it, so I took it upon myself to fan them out on his table. He’d added more magazines, so my name and former address were all over the table, again.

Pulling off the mailing labels, I started to see a foggy connectivity. I’d seen the vendor chum around with an old man who was always in the record shop, and I was once surprised to see him come up from what I assumed was our building’s basement. There was a door deep in my building’s hall, behind the recycling. I wondered at the time if he lived down there. Now I gathered he was maybe in cahoots with the vendor. I wanted to make sense of it, and these scenes seemed to fit. I figured I’d learn more from my experiment, which was now underway. I returned to Brooklyn and waited for participants.

*

In 2005 I moved to New York from Los Angeles, where I’d lived in a dingy, carpeted studio off an alley in West Hollywood. It was ridiculously cheap. Latino transgender prostitutes would store their belongings in blue plastic bags tucked into the tall hedges across the alley from my apartment. They’d arrive at sunset to change, and exit the alley as peacocks in patent heels to stand on the corner of Santa Monica and Poinsettia, my street, offering tricks.

I still associate the sound of rustling leaves and branches with transformation. When I’d see them, directly across from my two ground floor barred windows, I don’t know who was more startled by the other’s sudden presence: them, as they wriggled into tight dresses, or me, as I passed by with a dinner of toast and wine, headed to my desk to download more music from Napster over a dial-up connection. I came to know a small troupe of them by face and body, and we co-existed like that for six years, without communication and without issue, witnessing each other’s most private moments by accident and having the decency to look away.

I was an editor at an architecture magazine, and I’d taken an interest in offbeat homes, the kind we would never publish. A few weeks before I left for New York, I pitched a story to the LA Weekly about the items I’d find in the troupe’s home—those hedges. It was an infamous alley. The Weekly accepted, and immediately I hated myself for it. I felt like I was betraying them. It had seemed at first like an anthropological pursuit, a story I could report from a distance, but they were never more than fifteen feet away. Maybe I wanted to assert some ownership over our shared space, since their behavior sometimes made me uncomfortable—namely the sex and blow jobs outside my windows when they returned to the dark alley in idling cars with their clients.

I prepared by going across the street to the new Target on Santa Monica and La Brea, where I bought leather work gloves to protect myself during the job. I knew there were needles. When I finally stood in the alley before the hedges, a jar of Vaseline at my feet and blue plastic bags at eye level, I felt like I’d broken into someone’s home. I felt like a jerk. Nothing mocked my privilege more than my stupid new gloves. Even if I’d wanted to, I couldn’t have safely reached in. The bags were stashed so deep in leafy shame that my arm would’ve been gone up to my shoulder. The gloves ended prissily at the wrist. Disgusted with myself, I dissolved the story on the spot.

A few weeks later, I went to the laundromat early one Saturday morning, which was not my usual routine. The strip mall across Santa Monica was seedy. The expansive parking lot was a late-night spot for “dogging”—sex in vehicles in public places where there’s an open invitation to join in or swap partners. (There’s even a code with blinkers and headlights.) The area didn’t feel unsafe; it was a circus of consensual sex work as far as I could see, but I preferred to venture there in more public hours, or at least the clothed ones.

Anyway, after throwing in a few loads, I sat in one of the chairs by the large windows, where a strong beam of sunlight filtered in through the glass. I looked over and was shocked to discover that the prostitute I encountered most often was napping in the warmth, cupping the side of his face in his dirty palm. He had such a small frame, with delicate wrists and ankles, that I was surprised by the size of his hand. His long black hair was even glossier up close. He wore a night’s worth of stubble and male street clothes—a slim T-shirt and fitted jeans. The harsh light revealed a telling line of unblended foundation along his severely square jaw.

I shot out of my chair and moved to the back. I was terrified he would recognize me. We knew each other, but we always had the safety of barriers: the alley, the bars on my windows, and a difference of a few feet, to my advantage, since my ground floor was elevated. Those demarcations of space drew borders around our very different lives—his with the blue bags, mine with the prissy gloves. That morning we were two people who would potentially use the same dryer to spin dry our sundries.

*

I lived with the sex workers in the early 2000s, when voyeurism was nascent. We watched each other in person—not on Vine, not on Instagram or Facebook, not yet on Friendster. L.A.’s NPR affiliate, KCRW, had what was then considered a cutting-edge website. On the show page for Morning Becomes Eclectic, you could watch live video footage of the host Nick Harcourt. I watched him from an aerial camera that captured his every motion, largely uneventful as he sat at his desk, but enormously on the edge of something—that, you could feel. He invited viewers and, and like the reciprocal sharing of Napster, the mutual participation was thrilling, even perverse.

A dozen years later, with so many platforms to watch and be watched, privacy settings are like Venetian blinds that can be tilted for more or less exposure. I can’t help but think of social media and voyeurism when I reflect on my experiment. It’s loosely related, but I know my privacy settings. I have a heightened sense of control over what information I give away, so seeing my name on the street felt like an old-fashioned invasion.

Now when I recall talking to the stranger on the phone while a chill crept up my sweaty spine, I see that I’ve merged these experiences. In my visceral memory, I am talking to the prostitute in the laundromat. I am rummaging through the bags in the hedges that I didn’t want to open. I had been broken into like I had considered doing to the prostitutes, and my experiment had pierced the scrim in a way I hadn’t anticipated. I wanted to seal it back up.

Too late. The stranger was telling me what it’s like to live on the streets. Because he worked at night, he took naps during the day, when parks were open and safe. I was warming to his soft voice. I was also keenly aware that my full name and address were probably on the magazine he bought. What if he tracked me down at my new address, showed up at my door in costume with his rickshaw? Or at my windows? What if I let him stay in my apartment for a night or two? What if I fell in love with him?

I asked him which magazine he bought, and why. It was a New Yorker , the June 18, 2012 issue. He bought it because he liked the artwork on the cover, “ Soda Noir ,” by Owen Smith. It’s a pulp-inspired drawing of a man and a woman against a shadowy brick wall, holding a giant Styrofoam cup between them, expressions of terror on their faces. Smith told The New Yorker that it was in response to then New York mayor Michael Bloomberg’s plan to make large sodas illegal. “‘Are people really going to jail for this?’” Smith said. As for the pulp style, he explained, “‘Sex and violence always catches.’”

By the end of our conversation, I hoped no other participants would call. Despite my hesitation after this phone call, I continued to “donate” magazines, for weeks, but the sole participant was the seductive stranger who showed me my limitations with intimacy at the fringe, and whose offers for rickshaw rides I would politely decline.

He also taught me that there was camaraderie among people on the streets. The stranger said that they took care of each other. Before we got off the phone, he wanted to share some synchronicity he’d almost forgot to mention. He said that just a few nights ago he saw the vendor sleeping on the steps of Our Lady of Pompeii Church. The man’s blanket had fallen off his legs, so he jumped out of his rickshaw to cover him back up.

I thought it was beautiful, that the Italian immigrants’ fruit carts of one hundred years ago have given way to a passenger cart run by a superhero. Like the volcanic ash that preserved the ancient city of Pompeii, maybe the spirit of Father Demo is preserved there after all. The stranger told me on the phone, “I like seeing how people are living in this city, and I become a part of their living.” I didn’t really understand what he meant at the time, but I guess I’d overlooked street activity. New York is so different from L.A. in this way. In New York, because the street is everyone’s space, you create privacy through selective blindness. There’s only so much you can take in, until something teaches you to slow down, and see.