People Generations

When Cancer Runs in Your Family

In my frightened mind, so many people in my family had been reduced to that one word.

As a birthday gift, my mom wanted to take me shopping. I had one leg deep in a black over-the-knee boot when my phone rang. My mom, still smiling, took a fraction of a second longer than I did to realize: This could be the call we’d been waiting on. The results of my biopsy.

*

In April, around the time a lychee-sized cyst grew on my thyroid overnight, I felt a lump in my breast. The cyst was removed first, a silvery needle penetrating the darkness of my throat on an ultrasound screen, and tested for cancer: negative. But the mammogram showed a cluster of microcalcifications appearing like white freckles on the dark image of my left breast.

Microcalcifications are fairly common in general , most often benign, but in some cases, they’re the first and only warning sign of cancer. With your age and family history, the doctor said, they could be a red flag. Come back in six months.

In September, I received a letter reminding me to book my diagnostic mammogram. I placed it on the bedroom dresser, where I saw it every day but kept forgetting to call. Or so I told myself. Fear should act as self-preservation, shouldn’t it? But it often doesn’t.

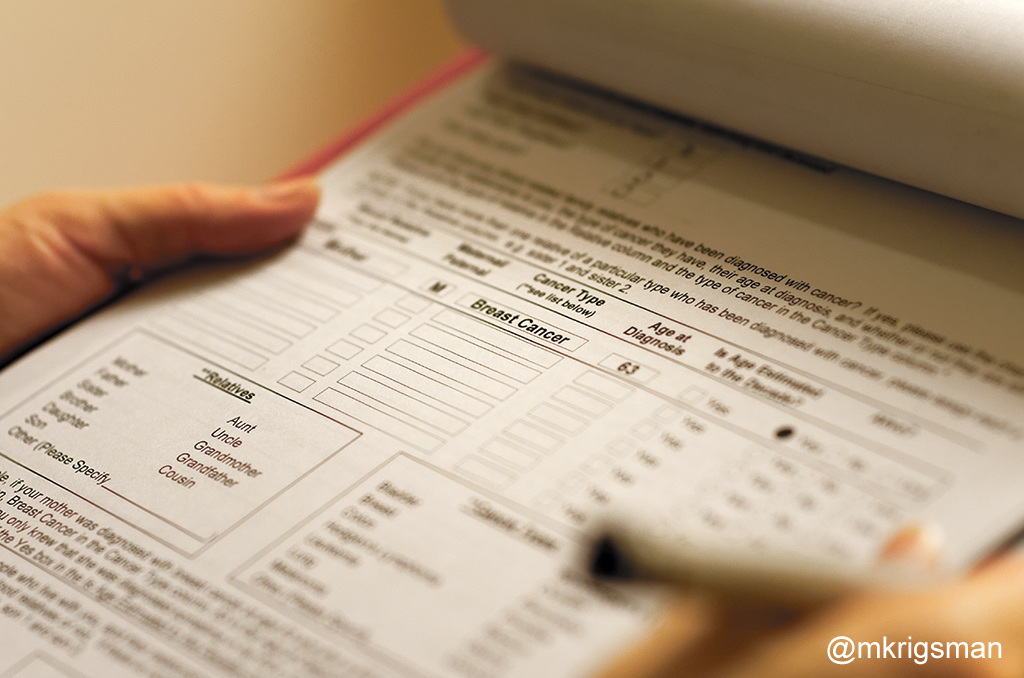

Finally, I made the appointment: October 25th, three days before my thirty-second birthday. Two words haunted me: family history.

*

My dad’s mom, Guela: petite and fierce, with a laugh that shook the walls. Fingers and wrists layered in jewelry from trips to South America and Europe, proud cook of “the best French fries in seven counties.” Unannounced, she’d come pick up my brother and me and take us to the lake, where we would stand on the marshy shoreline rubbing the wet dirt between our fingertips. She drove me through car washes because she knew I loved them—the windows becoming opaque with soap, the rising bubble-gum smell, the roar of the hoses. I always felt like we were in the belly of a whale.

Her bruises were the first sign. She was diagnosed with leukemia and went to MD Anderson for treatment, where I called her all the time. She was still so proud, telling the nurses how her five-year-old granddaughter had memorized the number.

I remember pulling a chair over to reach the wall phone in the kitchen late one night. My mom must have already told me that Guela would be going to heaven soon, to be with Jesus. I didn’t want Jesus to have her. She was mine. But that night, something must have shifted inside me. I told her I loved her, and that she could go to heaven if she wanted. And soon, she was gone.

*

The mammogram was quick, five or ten minutes in a small room, and concentrated on my left breast. Afterwards, I was taken into the radiologist’s office to review the results. The doctor was a blond-haired, blue-eyed woman in her mid- to late-fifties, wearing a skirt and wedge sandals. All the doctors I’d seen earlier in the year were men; one had said, walking into the room, “Boy, you’re a cute little thing, aren’t you?” I didn’t fully realize I wanted something different until I sat beside this woman.

Dr. M. was friendly and matter-of-fact. “These are your breasts,” she said, pointing to the mammogram photos backlit by a glowing white board. “This was back in April,” she said, pointing to the one on the left. “And this is today. Notice a difference?”

In both photos, the microcalcifications were clustered together in one spot, as if a saltshaker had been upended and quickly righted, the granules neatly scooped together. “There are more of them now,” I said.

She nodded and changed the picture, showing me another angle. The spots were like paper dolls, multiples of the same shape hidden directly behind the original. More than there initially appeared to be. “We’re going to have to do a biopsy,” she said.

She explained that she would use a hollow needle to collect as many of the microcalcifications as possible. Local anesthetic, an hour or two, results in three to five business days. Any questions?

“Percentage-wise,” I said, “what are the chances of it being something bad?” I couldn’t bring myself to say the word.

“One in four are cancerous at this stage,” she replied, saying it for me. “Your family history adds another 10 percent.”

The wind felt knocked out of me. Up to a 35 percent chance? One in three ?

I scheduled the biopsy for two days later.

*

One of my mom’s sisters was diagnosed with breast cancer in her late thirties. She caught it herself, her fingers detecting a lump missed by the mammogram. When she went into remission, the swell of joy swept us all up into its glittering current. Five years later, the cancer returned. Again, she endured treatment, and again, she emerged, making cancer seem winnable.

Then another aunt—my dad’s brother’s wife—received the same diagnosis. She was in her forties, a strong woman of style and confidence. She, too, went into remission, but when the cancer returned, it didn’t go away again. Her death was unthinkable. I couldn’t imagine how my younger cousins would survive it.

And then my uncle. My mom’s older sister met him when they were still in high school. He was all motorcycles and cigarettes, handsome as a movie star, a rebellious teenage girl’s dream. My mom called me only a few months after his diagnosis of lung cancer. Her voice was thick with grief and a sort of awe: He was her age . He had so much life left.

*

My husband, Adrian, and I sat quietly in the waiting room on the morning of the biopsy. He flipped through a magazine as I stared blankly ahead. Every so often he squeezed my hand or leaned in close, saying something that made me laugh despite myself. “Did you ever have bedazzled jeans?” he murmured, tilting his chin toward the woman checking in, whose back pockets sparkled with rhinestone crosses.

The exam room was freezing. Goosebumps rose on my skin when the technician, Lori, asked me to slip one arm from the pink gown I had changed into. To the left, my mammogram photos hung on a backlit wall. To the right, a stool led up to a flimsily padded metal table with a hole in the center. The doctor would be coming in from underneath. “Go ahead and slide your breast in the hole,” Lori said. “This is going to be uncomfortable. I’m sorry.”

“Do what you gotta do,” I said, all false bravado.

For the next fifteen or twenty minutes, she worked to get my breast at the right angle for the needle. She pulled and twisted, squeezed it between plates, said things like, “Is this position bearable?” and “You’re going to be more bruised from me yanking you than the needle!”

Then Dr. M. swept into the room, rubbing a firm hand across my back. She asked how I was doing before explaining the procedure. “Sorry this part is taking so long,” she said. “Your breasts are just so small it’s hard to get them at the right angle.”

Awesome, I thought. Thanks for that.

They continued to pull and twist and squeeze, and I wondered why they couldn’t have already shot me up with whatever numbing agent they were going to use . My neck was twisted at a harsh angle, and I stared at the choking hazard tag on the window blinds. Finally, Dr. M. injected me four or five times to numb me. “Poke, poke, poke,” she said, by way of warning.

After that, everything became more bearable. I felt pressure and pulling and heard a hollow mechanical roar, but my neck hurt more than anything else. Throughout the process, I felt one or both women’s hands on me, squeezing my hand or rubbing my shoulder or forearm. They said, “I’m so sorry, I know this is tough” and “You’re doing excellent, really great.” At one point, I told them, “I’m really glad you two are women,” and I meant it.

Half an hour later, they were done. “We got almost everything,” Dr. M. said. “They’re going to get you bandaged up. I’ll come talk to you in fifteen minutes.”

Two new women came in, faceless because my head was still turned toward the window, and hands put pressure on my breast, working to stop the bleeding before they applied Steri-Strips and gauze. When I was finally allowed to sit up, I was trembling uncontrollably. I sat on my hands while I waited for the doctor to return.

When she came back, she told me that I could expect a “big ol’ bruise, no extra charge.” I laughed, not because it was funny, but because it was over.

*

When my mom’s dad was diagnosed with esophageal cancer, we heard the news with the shock of watching a redwood fall. Poppi was a Marine, a cowboy, all lanky limbs and beautiful baritone voice, indestructible. But his prognosis wasn’t good. It was February, and he was planning a trip to Africa in August. The doctor told him not to book his ticket.

Visiting him in the hospital, I realized I’d never seen Poppi lying down. “Do the dance,” he told my grandma, and she burst into a giggling rendition of some goofy Fiesta Texas commercial. I watched him watching her, his face shining with love, and when she was done, he asked us, “Isn’t she beautiful?”

In June, I left to study abroad in Melbourne, Australia. When August came, my dad told me that Poppi wasn’t going to make it. I’ll take the first flight home, I said, electrified with panic, but my dad said, No, no. It could be two days, two weeks, or two months. They don’t know.

I was in class only days later when I got the call. I was so angry. Why hadn’t I left when I knew I should have? I could have been there. I could have said goodbye.

*

At home after the biopsy, I woke up from a nap to a throbbing soreness that made me lift my shirt to look at the gauze: the white had blossomed into a bright, startling red, and as soon as I sat up, blood trickled down my ribcage.

In a different room than before, Dr. M. and Lori helped me remove the sports bra and put on the pink gown. They peeled off the gauze and Steri-Strips and told me they’d have to extract as much blood as possible to avoid a golf ball-sized hematoma forming beneath my skin. Dr. M. apologized for the pain to come and distracted me with stories of her kids, and when my blood spurted, she joked, “This is why I don’t wear glasses anymore.”

The next day was my birthday, and the last thing I felt like doing was celebrating. But a buried-deep voice whispered, What if you don’t get another one? So I put on a red dress and the snakeskin Jimmy Choos Adrian had given me that morning, and we shared food and bottles of prosecco and laughter with my best friends, and I was so glad I hadn’t canceled.

The next day, we drove to Austin for Halloween weekend. It’s become a tradition for us—dressing in costume, drinking too much, dancing and making memories. I was Wonder Woman. Just beneath the left strap of my ridiculous shiny dress, the gauze bulged; underneath, a bruise spread a web of color across my skin. I couldn’t help feeling like the costume was a private joke with myself, an unmistakable irony as well as an obvious truth: Isn’t that what most of us do? Show the world what we perceive to be our strongest, brightest selves, even though the source of our power lies in our hidden wounds?

*

My grandpa was the Gutierrez family patriarch. Army veteran, entrepreneur, soft-spoken mumbler of magnificent proportions, my father’s mentor and best friend. I remember him in white muscle shirts when I was a little girl, when he would let me hang off his forearm while he bicep curled me. My dad always kissed Grandpa on the cheek as we said goodbye after Sunday lunches. “Love you, Pop,” he would say, and Grandpa would say back, smiling, “Love you, too, mijo.”

It was his dentist who sounded the alarm. There it was again, that word we’d all come to dread deep in the most frightened, painful parts of us: cancer. It was in his jaw, likely due to smoking. They would have to operate, remove as much as possible, and then he would need radiation. My grandpa responded with his typical stoicism: “Oh, well,” he said. “You play, you pay.”

The surgery was brutal. They took most of his jaw, but couldn’t get all the cancer. His face was radically changed, and if he was a mumbler before, now he was nearly incomprehensible—only my dad always seemed to know what my grandpa needed to say.

He was diagnosed in August, and in March, the call came. I was alone in Austin, and I didn’t know what to do when I hung up. Baffled and disoriented, I stumbled onto the upstairs deck and fell to my knees. Grief surprises you, strips you down, takes you to places that are new and familiar at the same time, primordial and ancient. So I knelt and prayed long-unused prayers, and they sustained me until I could be with the rest of my family.

*

In the days following the biopsy, my phone was glued to my hand. I kept checking the ringer and clicking the home button to make sure I hadn’t missed a call. When it came, there I was, trying on shoes with my mom.

I wished I had privacy, but there was nowhere to go. With one foot snug in that high-heeled black boot and the other pale in a white athletic sock, I stood up and claimed at least that one spot, that tiny patch of carpet, as my own for whatever came next.

“I’m calling about your biopsy results,” said a woman, after introducing herself.

“Yes,” was all I could say, and for a moment everything around me swirled white.

“It came back normal.”

I gasped and burst into tears, laughing and nodding at my mom, and accidentally hung up on the woman as my mom jumped from her chair to hug me. We were both shaking and crying. My mom called out to the sales clerk who was pretending not to eavesdrop, “Don’t worry, it’s good news! It’s very good news.”

My dad and Adrian met us for dinner a few hours later. I was still in shock, still exhaling big shaky breaths. In some ways, I had felt more emotionally prepared for the other kind of call than for this one. Normal. Normal was not what I had expected. So many people in my family, men and women, immigrants and entrepreneurs, soldiers and travelers, lovers of life in all its forms, had been reduced in my frightened mind to that one word: cancer. But they were more than that, of course, all along.

Driving home, I lowered my windows and turned the radio volume up. The wind poured in, heavy and humid and tasting of rain. I remembered being seventeen, driving fast in my first car, singing over the wind, feeling wild and free and absolutely invincible. It had been a long time since I’d felt that way. I grabbed that feeling from the air, from my memory, and I held it hard.