How To Turning Points

Writers From the Other Europe

“My new professor, with his reading list of Central and Eastern European literature, had handed me a vast map with so much good territory to explore.”

I was a nineteen-year-old from West Virginia, studying literature and geology in a southern college. The place was deeply conservative and monied. I didn’t fit in. At semester’s end, I thought I’d drop out—and do what? Write novels. Bumble through life. A friend was pouring concrete in Iraq, making crazy money, but the political implications of making dollars that way made me cringe. Another friend was pipelining in Michigan. Michigan wouldn’t kill me, physically or morally. I thought about all this while I stood in the hall, thinking about dropping out of college, waiting for Sociology/Politics 253: Peoples of Central Europe to begin.

Our professor for this new class was Krystof, a Polish émigré and the child of communist agricultural engineers.

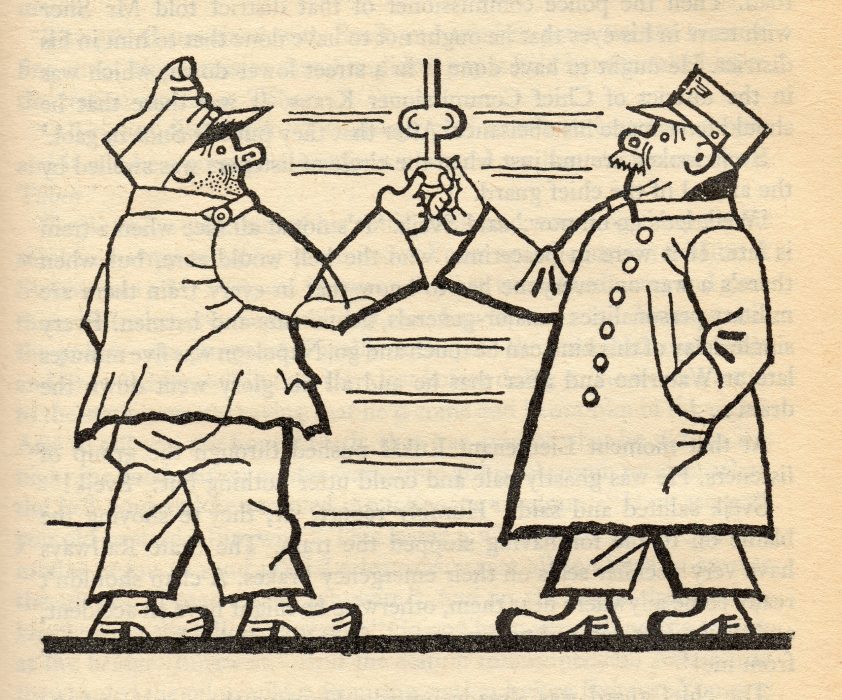

One of the first novels he introduced me to was Jaroslav Hašek’s The Good Soldier Švejk . In that novel, the passive Czech hero takes mongrel dogs off the street, forges their papers, and sells them as “thoroughbreds” to unsuspecting clients. What is wrong with that? The clients are happy, at least at first. Švejk can buy another liter of beer after each sale. What a magnificent display of cynology! All is well until he encounters bumbling police spies who suspect him of anarchism. He’s caught in the wheels of bureaucracy and government suspicion; he’s sent to fight in the Great War.

I lay laughing in the grass as I read The Good Soldier Švejk . I loved the riotous descriptions of the hero’s “unbelievable mongrel monsters,” one particular beast “reminiscent of a spotted hyena with the mane of a collie.” “Passing [it] off as a mastiff,” beating the system, Švejk won himself ninety crowns. Krystof told us that Jaroslav Hašek had been fired from a journal called The Animal World for writing articles about animals that did not exist. A man after my own heart.

Here it was, suddenly: this other literary tradition I hadn’t known I was looking for. The books Krystof introduced me to embodied such a different approach to writing and to the world. The texts became darker as the course went on. This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen —a collection of stories by Tadeusz Borowski that has also been translated as Ladies and Gentlemen, To the Gas Chamber. Then Closely Watched Trains by Bohumil Hrabal, about a timid railroad apprentice in German-occupied Czechoslovakia . Then Tadeusz Konwicki’s A Minor Apocalypse, in the Dalkey Archive edition with the gas can on the cover—a novel in which the protagonist wanders Warsaw, deciding whether to immolate himself in protest against the communist government.

My new professor, with his reading list of Central and Eastern European literature, had handed me a vast map with so much good territory to explore. The fiction I encountered in his course was so much more aware of the nuances of government power, and of silence, than the American work I’d been reading before. What else could I trace from writer to writer? A style that was discursive and cognizant of censors real and imagined. A style that was interested in erasure, and erased people. Books full of ruins and Soviet apartment blocks. Resignation. Black humor. The absurd. And these long, long sentences, Proustian but somehow more playful, incantatory. I had found my country, or one of them.

Moved by this, I sought out the Writers from the Other Europe series that Philip Roth curated for Penguin in the ’80s. Searching out those paperbacks in used bookstores kept me going through the lean times when I was young, broke, and crazy. This literature was a life raft for me.

When I was excitedly reading these non-American writers, I thought of the history of my homeland of West Virginia, so much of it logged to bare earth, burned over, and bought up by the federal government under the Weeks Act for the vague purpose of soil conservation. The US Department of Agriculture owns a million acres of forest, river, and mountain—acres which happen to be the landscape of my life and of my books. Should it be mined? Drilled? Can you shoot a bear? Two? Will this shaded area be mandated “Wilderness,” or that other shaded area instead? Policy in America is shaped so often by unelected men over conference tables. I loved the way the writers of Central and Eastern Europe I was reading were willing to write about what goes unsaid in America: that beneath the flash of elections, what shapes our lives is the steady hand of bureaucracy. I’d finally found a group of writers who faced up to the social force of bureaucracy in their work. Their bravery gave me the push to tackle this in my own writing.

My new story collection Allegheny Front explores the uneasy relationship between humans, animals, and the land—the three legs on which my wobbly world rests. In my work, extractive industry and government policy often pushes in at the edges of things, destabilizing them. More recently, the writers I discovered through Krystof, especially Tadeusz Konwicki, György Konrád, and Danilo Kiš, have influenced me in another fashion. Rereading their fiction, I’ve been struck by how they explore what it is like to live in a world with no future.

In A Minor Apocalypse, Konwicki writes that “our contemporary poverty is as transparent as glass and as invisible as air.” He describes “the monotony of living without any hope whatsoever, the decaying historic cities, the provinces emptying, the rivers poisoned.” I relate to that. The world that produced me is gone. Young people are leaving West Virginia, the coal mines are closed, the houses are going to ruin. I came of age in a generation there that was hyper-conscious of the fact that the place in which it lived was dying.

In absence of hope, a writer’s gaze is forced backwards. I find myself going back to my beloved writers from Central and Eastern Europe, looking for a hint.