Things Rekindle

Reading Underwater: Reckoning With Myself as a Woman of Color Amid a White Literary World

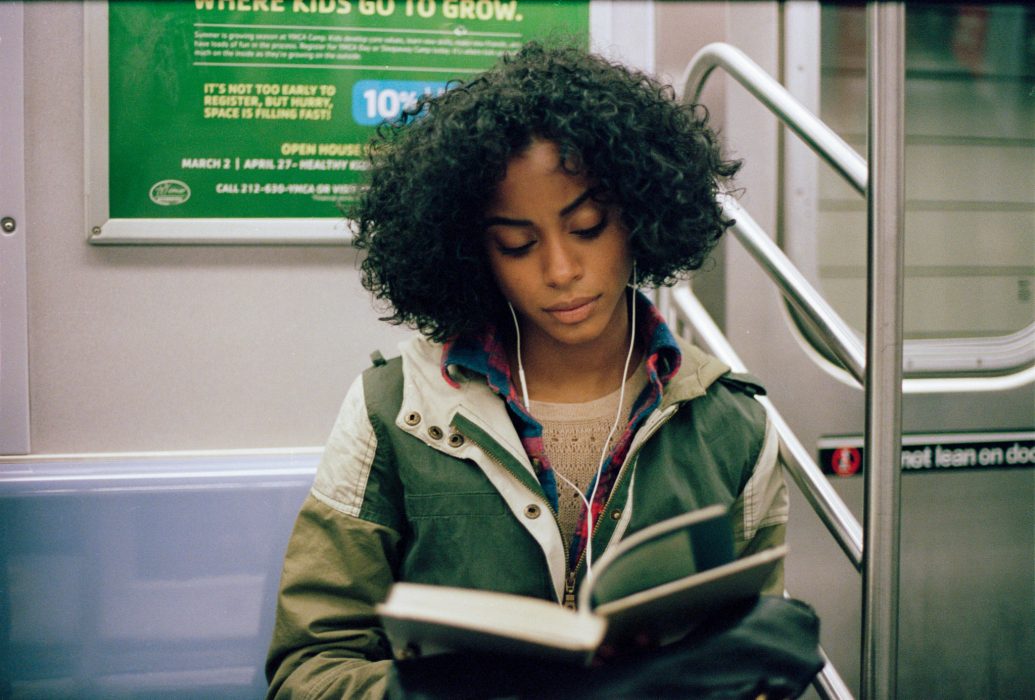

“My reading trajectory hadn’t equipped me with how I saw myself.”

What someone chooses to read is telling. What they refuse to read (or have pretended to read), even more telling still. We are often defined by the books we read, our reading journeys a divination of our previous lives within a life; a charted mosaic hugging the tides of our character development. The first book I ever read, at the impressionable age of six, was Enid Blyton’s The Enchanted Wood . When I say “first book ever,” I mean a book that was predominantly text, devoured entirely by myself with no parental figure looking over my shoulder. Going through individual stories more than once, completely enthralled by the adventures of Jo, Bessie, and Fanny, I quietly wished to elope to the Land of Do-As-You-Please. Like any delicate latchkey kid, the gracelessness of a lonely, rootless childhood was both moored by forces beyond a limited certainty and unhinged by a strange freedom.

The entire Faraway Tree and Wishing Chair series by the same author was discovered and promptly relished, my awkward self already starting to gravitate towards a comfortable home in imagined tales. The well-thumbed pages of these stories lent evidence to the fact that I had trouble easily making friends. If I had my head buried inside the pages of a book, the chances of having to communicate with someone else were reduced.

Adventure stories proceeded to color much of my elementary school life. I picked up books from The Hardy Boys series on classroom shelves and spent many a recess fervently embroiled in the mysteries Frank and Joe would help solve. Diagnosed with myopia in my second year, I was boxed further into a bookish demeanor that would continue to lightly shadow me for the rest of my life. The only people that paid any attention to me were English teachers who adored my composition writing, usually six to eight exercise book pages long despite their telling us to stick to a maximum of three. I didn’t miss the point! I was writing adventure stories. The next few years saw teachers lovingly thrust books into my hands: books that were sometimes unenjoyable ( A Christmas Carol ), outside my scope ( Jane Eyre ), unconventional ( The Borrowers ), and provocative ( Animal Farm ), but introduced realms just the same.

There’s a type of insouciance that comes with kids who grow up with a parental library, a little-regarded fixture that becomes indelibly part of one’s fundamental landscape. Shelves filled with existentialism and poetry, atlases, the books some parents want to project externally to guests, science journals and National Geographic , insights into lives previously lived. My parents are working-class folk who didn’t (and don’t) read, their only reading material an occasional newspaper or tabloid weekly after many a dull, tedious day. Dad would see me reading and ask why. “These books won’t make you money, child.” The only bookshelf we had in that home was mine. I envied, and still envy, friends who had the luxury to peruse their parental shelves, reading trajectories shaped by War and Peace and The Catcher in the Rye . In some way, I still feel behind.

If a failure to keep pace was a constant, it was because there was a dearth of motion in the first place. Who gets to decide our foundational arcs, other than the inevitable lot we were born into? The blooming I hoped for in the new environment that was high school didn’t occur. I still wore glasses (my prescription had tripled), my uniform was still baggy, and I still had trouble speaking to people. Gendered socialization—which had already begun to take root under my nose in the years before—was rampant and in full, alienating view. And because I hadn’t paid attention to social cues and was largely left alone both in school and at home, I didn’t, and couldn’t, identify with rituals that were heavily embedded within socialized, gendered constructs. It wasn’t that I was actively divorcing myself from gender, or was trans; I just hadn’t noticed. What was trusted to be a resource in the world of words was insufficient.

Falling in with groups of nerdy boys in high school, then, was almost effortless. While they welcomed an oft-absent female presence, I clung on to their company with grace. Giddy with a sense of capital-F Friendship, it was a like-mindedness that was at once strange yet secure, and an understanding of power that was attendant to being part of a group. Laughing (at ourselves and at others) came easy. Conversations, however tricky, filled an inner void. It was the same mutual to-and-fro I had with myself up till now, except the thrilling anxiety was in that I couldn’t predict what happened next. And what did happen next involved a lot of crime and military fiction, books “my boys” read. I was behind again, but I caught up, plowing through 1000-page Tom Clancy epics (a struggle), Clive Cussler thriller series (terribly designed covers), nearly the entire Stephen King bibliography (trite after ten), Ian Rankin’s Detective Rebus books and their banal plots. Another genre of stories that had been overlooked in the past opened up: Philip K. Dick’s, Isaac Asimov’s and Terry Pratchett’s otherworldly sci-fi and fantasy empires, spheres of reality that I find myself still partial to.

“Keeping up with the boys” during those fragile, formative years set me on a certain path. Even after the dust of high school had settled, and my friendships with these boys long drifted apart, I found myself pulled toward a particular kind of voice—what I deemed a “masculine” voice: staid, to the point, cheeky but affectless. College years found me slightly solitary again, with days often ending in a solo trip to the library to see what was on offer. What should I read, now that I was back on my own again? Douglas Coupland’s JPod in a bookstore led me to a self-made (albeit analog) algorithm that involved the likes of Dave Eggers, Jonathan Safran Foer, David Foster Wallace, and Chuck Palahniuk. You Shall Know Our Velocity was a heartbreaking work of staggering genius; Everything Is Illuminated possessed a tone I tried to mimic for years; Infinite Jest was an undeniable postmodern epic. Lullaby was transgressional enough to cause the latent passive aggression within me bubble up to the surface. I dropped out of college. By that point, I had racked up huge bibliographies of books with characters that were so removed from any crystallizing sense of self that I inadvertently desired to be them.

There exists painful distinctions between learning and unlearning. While in some ways these books formed a large part of who I am, I now know that teasing apart these subtleties is often an indicator of what I am willing to give up, hold on to, outrightly reject, or look upon with fondness. I could scorn the “bro” lit of Coupland, Palahniuk, and Tao Lin for hours, selectively critique the film adaptations of Stephen King’s novels, and laugh at the whimsy of Jonathan Coe and Safran Foer with a sort of maniacal glee only the too-familiar can elicit. But I hold the fantasy of Terry Pratchett as a cornerstone of the widened boundaries of my imagination, while the fantastical worlds of K. Dick’s and Aldous Huxley’s were a foreshadowing of our current dystopias. Unlearning is relinquishing what is no longer useful, yet taking these same parts to build a larger and more forgiving version of ourselves.

In Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness , the author, in the voice of Genly Ai, solemnly concedes it is good to have an end to journey toward; but it is the journey that matters, in the end . And: Who will see it in the darkness of my leaves? Who will count the number of them? Speculative and philosophical, the book would become the one to begin a lifelong unlearning, one that would upend ideas of gender and the future, while confirming pre-existing uncertainties, precariously held on to all along.

And so, at twenty, working dead-end jobs and still socially inept, I discovered and was thrown into the world of punk subcultures like a moth toward the light. The world of zines lit that well-trodden road, and concepts that were at first unknowable became pillars of strength. Through these zines, I was introduced to Le Guin’s books amidst relevant political praxis—feminism, gender and race politics—that simultaneously corresponded to a sense of being yet gingerly carried a sense of estrangement, a double consciousness that even a decade later is still a work in progress.

The Handmaid’s Tale followed. Then The Bell Jar , Virginia Woolf’s Orlando . Zadie Smith’s White Teeth . Susan Sontag’s I, Etcetera . And so on. The capital-F Friendship that always seemed fleeting before came easily within a crew of misfits, friendships that felt comfortable but not overly intimate, where recommendations were the main dispatch. These recommendations, despite sometimes being a sneaky entryway to inflicting a meek superiority over another’s intellect, seemed like a way of establishing tenderness without ever getting too close. Groups of dorks against the world. Everyone was my friend. We were all friends. I had friends! Most importantly, they weren’t all men.

Another note on unlearning: It gets tricky, and sometimes it gets bitter (not better). The double consciousness that involves seeing yourself through one lens, while others see you through another. My reading trajectory hadn’t equipped me with how I saw myself, even as the layers were slowly coming apart. Like an unraveling spool of tape, the journey abruptly stalls before we figure out how to put the bloody thing back. And with Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior, the disentangling began anew, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah at its heels. Like the whodunnits of my childhood, it was a quest to the bottom of the mystery of myself. For the first time in my life, there were passages I could nod to, not just because its style was striking, but because I was astonished at its relevance.

And so it goes. In 2016, I made a pact with myself that I would only read books written by people of color. I needed to know: Who am I? And how does the idea of myself as a woman of color get crystallized? In an attempt to decolonize the mind, my appetite was limitless. The books that especially defined this period were phenomenal in their scope: Teju Cole’s flâneurs who would ruminate on space and race ( Open City ); Madeleine Thien’s visions involving a Chineseness I could understand ( Do Not Say We Have Nothing ); Helen Oyeyemi’s arresting prose involving the subaltern supernatural ( The Opposite House ); Yiyun Li’s melancholia surrounding mental health and migrant displacement ( Kinder Than Solitude ).

Reading is a type of reckoning with the self. That may sound like a simplistic platitude, but platitudes exist only because they are true, our self-serving intellectual mirrors be damned. 2016 ended with no white author in sight, and for that I felt an array of feelings: pride, self-importance, contentment. Pride because it was a proper effort in itself, an effort that required hours of scouring and referencing beyond bestseller bookshelves; self-importance was a pillow resting at the bottom of that silly sense of superiority derived from finding missing pieces of a lifelong puzzle; contentment as I have transcended (and happily betrayed) my previous selves. This effort will continue, this peculiar disentangling (decolonizing) always an ongoing process. I’m still behind, but I’m catching up. Finding a home inside yourself can be the most illuminating surprise.