Things Rekindle

How to Read Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s ‘Americanah’

“I am three days aged in Lagos and cry as my fingers turn the first page.”

1.

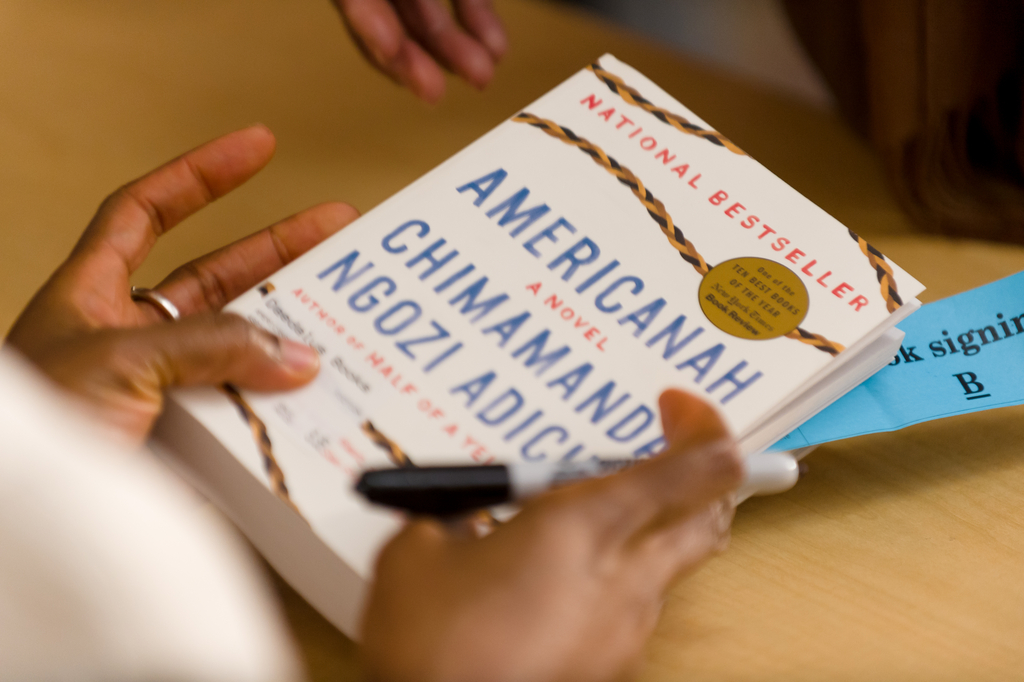

My first year in Lagos, random people tell me that I remind them of Ifemelu, the main character in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s bestseller published that same year, Americanah . I bring my copy from New York and see hawkers selling the Victor Ehikhamenor illustrated cover in go-slow traffic in Victoria Island on the way to work every now and again. The first time I read the book I am three days aged in Lagos and cry as my fingers turn the first page, because I am reading a Nigerian woman in Princeton, while I sit alone in my aunt’s room in Lagos. The homesickness catches me.

As I sit on the chair close to the window, it is almost dark when I get to the end of the book and come across the line where Ifemelu says, I discovered race in America and it fascinated me. I close my hardcover copy for the night with a long pause, leaving the final eighty pages for the next day. That line— I discovered race in America —stays with me for days, and I try to make sense of it, even though being here in Lagos has made me consumed with the exact opposite. What does it mean to be a black woman here ?

2.

“I’m a feminist because of my grandmother!” This feels like a solid answer to the question many men in Lagos ask me. I try to believe it in conversation and debate with lovers and strangers. To them my feminism cannot be rooted in Nigeria, and I can think of no better way to silence them.

I have moved indefinitely from New York to be an artist. Writing and thinking and making in New York for the online magazine that wants to write about Africa isn’t working for me anymore, and I think in traveling the distance I can make up for the attempt. I see an idea of myself, writing and thinking and making and living, that feels unattainable in New York. So I quit my job, I get on a plane, spend three days with friends in London, and then I am here.

Standing in the kitchen, cooking for him. I don’t mind the labor of cooking. I have been warned from a previous Nigerian lover that it was impossible to deal with me—I was too radical. But this has nothing to do with cooking—what men and women alike could consider to be the quintessential act of submission. You cooked for them? Yes, I love cooking for others, making intuitive guesses about they would like to eat. He says he doesn’t like fancy food so today I’m making sweet chili pepper spaghetti with garlic leaf roasted chicken.

I roast chopped onion, scotch bonnet peppers, tomatoes, and leeks in the oven for two hours; the small one-bedroom apartment isn’t taking the heat well, but I don’t mind sweating. There’s no electricity so he tells the man who guards the gate to turn on the small generator; I bring the fan inside to help with the smoke from the charred roasted vegetables. Blend them. Sprinkle cumin, garlic powder and pour a dash of Spanish red wine I buy from the pharmacy a few minutes away in the sizzling pepper sauce. I’m saving the rest of the bottle for the dinner. He doesn’t step inside the kitchen while I’m cooking. I imagine he is giving me space to make magic. I brown the butterflied chicken I’ve massaged into the wet mixture of garlic leaf, tarragon vinegar, honey, salt and pepper on both sides. The pink juices will turn clear after it spends some time in the oven.

We finish eating and laughing and cuddling and then it is time to leave. The gate at my aunt and uncle’s will close at eleven, and I only have a few minutes before my late entry becomes the topic of conversation between my aunt and me the next morning. How it is not safe to drive even just five minutes at night in Lagos. This is not New York, she will remind me.

While I was cooking I washed up the pots and bowls and spoons and spatula I used to make his dinner with leftovers through the next few days, left the rest of the dishes he and his brother have messed the night before in the sink. I grab my bag from the chair by the sliding front doors and now he looks annoyed. Are you going to leave all that, he asks me. Yes, I say. I have to go. He sighs. I made dinner, doesn’t that mean you’re on cleanup, I say. His eyes are beady and red. Just leave, he says.

But he is not asking me nicely . The brown leather bag resting on the small of my shoulder falls on the sticky tiled floor. I can’t believe you would say that to me. I’ve been in your kitchen for three hours making dinner for you—why should I feel bad for not cleaning up the mess you and your brother made last night? Would you clean up the mess if I had my own place? This time he doesn’t ask. Leave. Get out. No, I shout back. How dare you? This is never going to work if you think I’m supposed to clean up after you. What the fuck is that? Now he tells me not to swear at him, but I see the red of the peppers I have roasted for hours and I yell. I tell him I can’t be in a relationship with someone who doesn’t have respect for women. I push the sliding door so hard it shifts out of the track.

I’m almost at the gate when he catches up, closing the slightly ajar gate door two steps behind me. Why would you walk away in the middle of a conversation he says. The walk from the door of his house has calmed me, albeit slightly. Where my heart was beating quickly with anger, now I feel the shock and sickness below my stomach. The house in front of his boy-quarter flat is empty, and I know no one can hear, so I listen. He tries to explain it to me: A real Nigerian woman would never leave dishes in the sink for her boyfriend to wash!

“Maybe I’m not a real Nigerian woman,” I reply.

This relationship will not last long. But I will stay. I will cook for him again, only when the steward that cleans his house twice a week is around to washes the dishes. I don’t want to be the American girl who says no.

I am always having these conversations with men in Nigeria. The question of my allegiance to feminism follows me as if I am the ball of eba lodged in my partners’ fingertips, while his okra soup sticks on me with a slow and slimy draw, except I do not want to be eaten.

I wonder if the woman that drives the Land Rover and lives in the compound next door has this argument with her husband every evening, or if there’s something about me that makes men here want to catch me only to contain me. I don’t know if all women in Nigeria are oppressed but I know that I walk heavy here on unpaved roads in slow strides trying to manage the sink of potholes, and that it feels different to the weight I feel in New York.

3.

My grandmother’s world lies with her in bed. She shares a full-size mattress with a portable radio broadcasting news in Yoruba, crumbled nylon bags, a plastic back scratcher, a flashlight, a jar of pink nail polish, loose Naira notes, tablets of medicine, and monogrammed notebooks only a seasoned party-goer could amass hopping from one party to the next on Saturdays around Lagos and Southwest Nigeria, even at the age of seventy-eight.

I push aside a canvas tote from a party she attended on June 5, 2014, and take my seat on the smaller bed opposite hers. I haven’t been to this house in twenty years. It is quiet, and cluttered yet empty. The first time I visit this house, I am eight, on my second visit to Nigeria from New York with the entire family. Grandma and Grandpa’s house is crowded with six aunts and uncles and five cousins, celebrating Mother’s presence in town. The ten chickens roaming and clucking through the grass in front of the two-story house will remain five by the end of the night.

Grandma had more weight on her body then; it is hard to believe she has seven children. My sister and I are running through the downstairs of the house until we run out of breath and settle in front of the TV where uncle puts Power Rangers on. This is my second time with Grandma and Grandpa. I do not know then that I have another Grandma I will greet through Grandpa every time we speak on the phone in the years to come. I only know that we are all here, and there are more of us. Cousins, aunts, uncles, goats, and chickens that are somehow part of the family. I sing the Power Rangers theme song with little brother between my mosquito bite-ridden legs, so that the adults can reminisce on time lost. Grandma’s house is far away, and all my friends see Grandma and Grandpa on weekends, but that is not an option considering I spend school year weekends in New Jersey playing with white dolls.

Grandma is stern, yet warm. She is pretty and looks just like mom. I try to find the resemblance—her cheeks are round yet they have an angle on the cheekbone, just like mine.

Grandma finds us in front of the TV and says Ekaaro and I reply Ekaaro Ma. I have been practicing with Mom and Dad in New Jersey. It is nice to know the answer to the question she asks me. In these twenty odd years we have never made it past Ekaaro , a greeting that once made me feel part of something.

I am hoping now to get to the root of something. I have heard bits and pieces from mother and aunties but I realize that I know nothing of my grandmother, other than her “no time for nonsense” temperament. Since I learned of her separation from Grandfather, I have spent much of the time ruminating about her decision to live separately from him, and I even asked him what happened a few years ago, but I have never asked her.

In those years, so many things were unsaid, so many projections carved into an indestructible sculpture of a grandmother and her American kin.

4.

When I first move to Lagos I am looking to make art about old women who protest naked. Research from my time in Evanston and London left me with a question for which I still have no answer: How does the colonial history of naked protest in Nigeria allow us to consider the creation and signification of the black female body? A theoretical doozy. But of interest to me is how this history connects Nigeria to blackness in a way I can grasp.

When colonial officers would wander around the country not yet known as Nigeria, taking photographs and documenting our cultures, they were surprised to find so many different meanings of nudity and nakedness. They find that in precolonial Igboland, where the first mass protests during the Women’s War take place, there are different sociocultural contexts for the bare body. Even when unclothed, the body was not necessarily naked. The colonial officers run and hide when the women come to their offices threatening to bare all during the Women’s War. History records this, yet it never names their bodies black. I decide I will record it myself.

I begin the search for women in an image I find online while doing research for my dissertation at LSE’s Gender Institute a few years prior. The image shows two women, bare-chested, caught mid-stride, surrounded by other women also partially nude. The article from 2012 says they are protesting about land, but it does not mention that these women are not too far from where Nigerian activist Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti once led a group of women to protest naked at the palace in Abeokuta, then Egba in 1947, about taxation. I think that they must know.

Now in Lagos, a driver and I journey almost three hours, first through paved roads, then through wet sludge, and finally up steep and rocky hills, and then we find them.

The driver parks the car and with a man who represents a local government within the same constituency we have picked up along the way, we descend from the car and introduce ourselves to a woman sitting on a rusted chair, an aluminum bowl of dried maize at her bare feet. My Yoruba is elementary at best, so the man tells her that we’re looking for women who protested naked a few years ago, in the same clay strip we stand on. She cuts his inquisition short, and tells us to follow her. My eyes follow the path she lays with mud-stained bare feet to a group of men, a few meters ahead.

The four men are chatting against a small white building. We exchange back and forth: Who do you want to see ? The women in this photo, I show them on my phone. Which organization are you representing? I am not here with an organization. You don’t have any identification? I rush back to the car to get my work ID card from my purse on the front seat. I hand it over to the man who speaks English, fingers shaking. Finally the men are satisfied.

The woman introduces herself, and says she will see if she can find any of the others, if they will have my time. I set up the camera and tripod, hands still quivering as I try to insert the memory card into the slide, finding success the fifth time.

Four women arrive. I ask them what happened that day. The answers flow and flow, I forget the camera is even there. I ask them if they had heard of naked women protesting before them. I ask if they have heard of the curse of nakedness—this is the term the scholar Terisa Turner uses in her book I first read in Northwestern’s Herskovits Library of African Studies. Now it’s mentioned whenever anyone writes about African women protesting naked. It’s never happened before anywhere they say. I tell them it happens all over Nigeria; it even happened in their state in another area just last year. I almost ask it: Are you a feminist? But I already feel ashamed, like I’ve told them who they are before asking. I don’t bother saying the word I know I cannot translate.

After I pack up the camera, I remove the box of Indomie noodles and canned goods and place them on the steps of the first house on the mud path as a thank you for their time. They are grateful. I do not get what I came for, but as we drive down and down the hill, stopping only once midway for men with rifles hanging over their shoulders in plain clothes, my heart beats quickly trying to find the question that brought me here to begin with.

5.

“I’m a feminist because of my mother!” I cannot remember her ever saying the word, “fem-i-nist.” I imagine the heavy word rolling off her tongue now with a twenty-six-year-old Nigerian accent that has aged twenty-nine years in America.

It is the night of my first group art exhibit, an art competition. It has been two years since I moved to Lagos as an adult, and I have driven back and forth to Freedom Park in Lagos Island three times today to pick up an extension cord, a stool, and change. The art gallery is a small rectangular glass building on the perimeter of the large park, reflecting hues of a stubborn sun almost ready to set. On my last trip back to the apartment, I collect mother. She has come all the way from New Jersey to Lagos to be here.

During the opening reception I spend as much time as possible away from my own work. I have little desire to see people walking around in a zigzag formation through the open wood installation I have made. I chug a friend’s plastic cup of red wine when I am out of mother’s sight, not wanting to offend her halal sensibilities with the need to calm my nerves. Whenever I glance at my piece, outside of the building or when I look down from the second floor of the building, I see mother standing close by. She tells me later that she helped explain my piece to someone who was inspecting the wooden boards imprinted with an old newspaper article from 1948 about women protesting in southwest Nigeria. I do not invite Grandma this evening to see the work I have made about old women and their bodies.

When the award ceremony begins, I sit just behind mother and her sisters with three friends. Three awards will be announced, and I am hoping to win one. The master of ceremonies asks the guests to settle down in rows of velvet red chairs in front of the stage edging the gallery where the work rests. He introduces the twelve participating artists and somewhere in the middle he lands on me. The large projector screen to the right leafs through images of my work and the announcer says:

“Maryam Kazeem is a writer and artist whose work focuses on the memory of naked protest in Nigeria. Her work asks us to consider the memory of women . . .”

“I know there’s no auction tonight, but put me on line cause I’d love to bid on her,” he chuckles through the last words and pauses to allow for some laughter from the audience. He introduces the other artists and their works without another joke.

After the ceremony, it is hard to feel my feet. I take each step slow with intention, afraid that I might fall over from anxiety about the whole thing. I am okay that I do not win an award for my work, but it stings that my debut as an artist is couched in the man’s infantile sense of humor and desire. I am standing in a row far from the stage with Mother, holding onto the gold chair frame when she grabs my hand and says, You did such a good job.

It is dark now and the air has cooled a bit, no longer sticky and stubborn.

“Did you hear what he said?” I ask, my arms crossed. “The comment he made about wanting to bid on me, it was so inappropriate.”

“Oh he didn’t mean it like that, it was a compliment,” she insists while reaching to smooth the crease of the golden yellow, purple, and white kente cloth skirt that sits high on my waist.

I push her hands away lightly and tell her it was unprofessional and unacceptable a few more times, but our conversation isn’t going anywhere. I want her to join me on the front lines of indignation, but she cannot fathom why I am bothered enough to march in the first place. He just thinks you’re pretty.

Despite her protest, I find the man and give him a piece of my mind. He apologizes, and feels misunderstood. “I didn’t mean to be inappropriate,” he shares, with wide eyes and a tone of surprise that he has been disciplined this Thursday evening.

Later that night when Mother and I are sitting on the couch in the living room of my apartment, she rubs her feet against mine. Her feet are cold, and I am about to complain as I normally do when she does this.

“Mom,” I start.

She turns to me, eyes heavy, waiting to shut for the last time tonight. I think to throw her legs off the couch. She is so capable of getting angry with me, or my sister, or my brother, or my dad, but never with it .

6.

One of the articles the main character Ifelemu posts on her blog is called “To my fellow non-American Blacks: In America, You Are Black Baby.” I wonder the day a coworker sees me at the cinema in Lekki and tells me through what he believes to be a charm-filled smile, You are really beautiful for a dark-skinned girl , just who we are fooling. It surprises me then that in more than twenty-five years in America this interaction in Lagos is my first time receiving those words to my dark face.

7.

Grandma thinks I am not sure of what I want to ask, but I am not sure that she will understand me.

Early last year, both of us sitting on the suede couch in my aunt’s duplex on the other side of Lagos, I grill her about Grandpa’s decision to marry a second wife, and she gets frustrated with squinting eyes, “There is no malice between me and your grandpa,” she says. I can tell my questions are getting to her. At just five feet tall, the cataracts in her eyes have formed a new scar just below her right eye, from a tumble down the stairs the year before. Two symmetrical indentations sit at the bottom of her cheeks, ila or tribal marks from when she was just a child.

When I’m pretending not to interview her, I learn that my great-grandfather had seven wives and nineteen children. Grandma is the first daughter. A station master, Great-Grandfather moves around constantly and Grandma is still in form two by the time she is seventeen, never feeling the sensation of turning the last page of her school books, provided for free courtesy of then British policy for free education in the colonial territory. She meets Grandpa around this time and their courtship will lead her to drop out of school due to her pregnancy.

Tall and lean, he has just returned from the UK where he takes a course in hospital administration in Cambridge. He spends free time at his uncle’s house just around the corner from my great-grandfather’s house in Ibadan. With a tease and a few inside jokes, she leaves her father’s house and enters his.

By the time Grandma and Grandpa move to Lagos, they have three children and four more to come. “If I had been born in this time, things would have been easier,” she says. “My mom would have helped me manage things.”

In other words, motherhood could have been an event and not the event. After the family settles a bit in Lagos, Grandpa offers to send her to teacher’s training college. Yet it is in 1964 at his own mother’s wish that he asks her to stop studying.

“Face your children,” they say.

8.

Women in Nigeria have marched, danced, occupied, sang, and cried to say no. Sometimes we talk about it, but most of the time we don’t. Rarely do we name it.

Only once does Grandma share details of what happened when my grandfather has an affair and their family expands so that it almost explodes. “When he confessed, I was so angry,” she says.

“What did you say to him?’

“I slapped him.”

“But you’re still married?

“Yes, but it doesn’t matter. If he has love, I’m interested, but if he had love and interest in me, he wouldn’t have married [her].”

“When did Grandpa move?”

“I can’t date it, because where there is no love there is nothing. I’m not interested in his life again. When he was going to Osogbo, he asked me to come, and I said ‘What am I going to do at Osogbo? All my children are in Lagos. So I’m not going to Osogbo, thank you very much.’”

Grandma takes pride in getting dressed every morning: matching shoes, jewelry, and bag even for the mundane task of getting on crowded yellow Danfo buses so she can move around Lagos to stop in and stay with her children for days at a time before returning home. She is not the woman who holds onto sorrow. She manages her pain well. I forget but I don’t forgive , she says.

9.

We are searching through the closet.

As we sort through aged wax prints and intricate lace fabric, I find a clear plastic bag sandwiched between two wrappers. I unfold the plastic and pull out a white polo shirt that reads “Lagos Women Association” in navy blue ink. Below there is a sketch of a woman with hoop earrings, a tied scarf on her head, and a dress made of the Nigerian flag, green and white. On the other side it says “UNITED WE STAND”.

I try to hide the grin on my face, my impatience seemingly appeased. “Where is this from? I didn’t know you were part of a women’s association. I asked you and you said you didn’t do anything like this?”

“This?” she asks, bringing the shirt close to her face so she can make out the words on the front. “They asked me to attend one meeting many years ago, talking about politics. Me, I wasn’t interested in anyone coming to kill me. I never went again.”

Why the need to mythologize the elderly? To look for what we presume to be hidden. Grandma’s life is tucked into shelves, lays on the bed with her, and nailed into the walls. In Grandma’s eyes feminism, which I define for her as justice and equality for men and women, was never meant to be for everybody. She doesn’t believe everybody can be equal. She does believe that heartache and loneliness can be managed for the sake of the greater good.

I know she is tired of being questioned, so I ask, Is there anything you want to talk about? Maybe something you’ve wanted to ask me? I feel silly asking like this, but I want to open up the conversation. We have moved past Ekaaro , but it feels unfair that I’ve opened old wounds, so I press again. Anything you want to know? She smiles and shakes her head. No? I press, voice slightly rising. As long as you are fine with work, I only want to know where he is, she says.

Him, I ask?

Yes him, I want to live to see great-grandchildren, she says.

My brows are raised now, irritation causing sweat to form under my armpits, but I look up at her and reply insha’Allah to satisfy her. It seems we’re having a different conversation, meanings muddled, intentions unclear. I can’t seem to find that part of me here with her, and it seems so clear that is the whole point of this thing called the f-word. Liberty.

10.

I do not come to Lagos to learn how to manage.

People ask why I am a feminist almost as many times as they ask me with curiosity, Why did you decide to move to Nigeria , or better, Wow you’re still here, when I bump into a friend’s friend at one of the few weddings I attend.

Lineage is the thing I turn to—my parents do not live here, but most of my extended family is in Lagos. This eases them a bit. Some have called me brave for making a decision that sometimes makes me feel cowardly. Like I’m here because I couldn’t hack it in America.

But Grandma loves that I am here. In the first year when we speak on the phone she announces with delight, You are really a Nigerian now .

All the art and the women and the research and the writing and the feminism sound better than the real answer. That I am looking for a place that tells me that who I am, what I am, is okay. That I am looking for love. Not the romantic kind, but the kind of love that surrounds and justifies. A love like home.