Things Curiosities

El Hugé

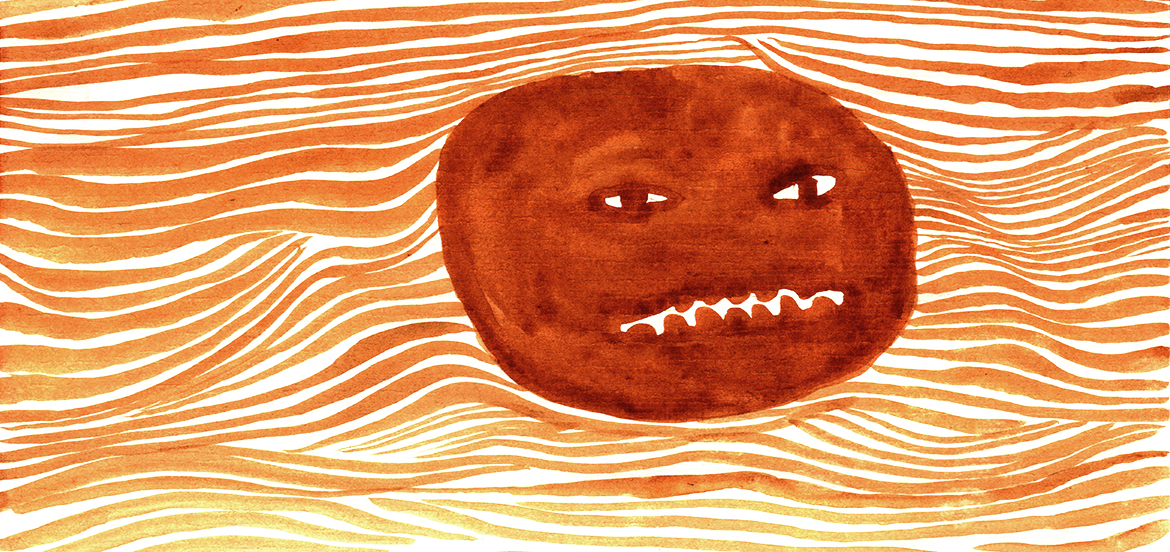

A twelve-hundred pound pumpkin threatens California-area teenagers.

When I was fifteen, I slew a giant that had done me no harm. I had to do it. There was no other way.

I lived in the kind of town that nobody believes exists anymore. An hour from any freeway, we were surrounded by oranges on one side and cows on the other, with tumbleweed traversing the valley when the wind kicked up. This wasn’t Oklahoma, it was southern California.

In a yearly culmination of a fall harvest festival—because Halloween is pagan and somehow a harvest is not—farmers from all over the valley brought in the biggest pumpkins they had grown. There were no prohibitions on performance-enhancing drugs in this squash Olympics; people tried everything from Miracle-Gro to burying their gently radioactive Fiestaware in the dirt. The pumpkins grew monstrous, sloping and misshapen, formless under their own mass. Their coloring was like cancerous flesh. They had no beauty, only bigness.

The biggest one that year was El Hugé ( hugh-gay) ; over twelve hundred pounds of pale, ghoulish, inedible pumpkin. The farmer took a blue ribbon and the paper got his picture. The gourd sat out in the Indian summer heat on public display.

In the purpling night, long after school had ended, I sat forgotten at the edge of a parking lot. I was debating whether to give up and try sleeping at a friend’s house, or to keep waiting for someone who was likely never coming. My indecision was broken by a guy named Cole, dangerous and sexy at seventeen, with a scar like someone had dripped hot candle wax out of his eye socket and onto his cheek. He drove a beat-up black pickup truck with red duct tape playing understudy to taillights. I didn’t think twice when he told me to get in.

I was the kind of girl who would have slept with him for a smaller kindness, but that wasn’t what he was after. We picked up two of his friends, black-leather types, who crawled into the jump-out seats wedged behind us in the cab of the truck. One friend carried a swollen backpack that Cole referred to as “the supplies.”

“Supplies for what,” I asked, hoping that I was at least going to be subjected to peer pressure over drugs and alcohol. My peers had something else in mind.

“For El Hugé.”

The pumpkin had not been named by the farmer or the newspaper. It was one of those things that just arrived one day, like an urban legend that everyone knows but no one can trace. Bad Spanish is a badge of honor among poor whites living in what was once Mexico, and so El Hugé was his name.

I didn’t protest. I didn’t suggest that this might be a bad idea. When the boys lined up long pieces of lumber to build a ramp and began to push the pumpkin into the bed of the truck, I jumped out and put my back into it.

Somehow, we loaded the thing. The truck groaned and the shocks were compressed. One of the tires scraped in its wheel well as we crept out of the larceny lot. But we got away.

In a dry riverbed, miles out of town, we shoved our vegetal hostage back out onto the ground. It settled malevolently on its flat side.

I don’t know how we came to this conclusion because not a word was said, but we hated El Hugé. That pumpkin’s existence was somehow inexcusably offensive to us. Cole outlined a crude jack-o’-lantern face on its ghost-orange skin and one of the other boys stabbed the sappy adipose flesh with a long knife he had stolen from his mother’s kitchen.

We couldn’t cut a face. It took our combined strength to sink or remove the knife and we were soon exhausted.

Cole looked over our handiwork and said that surely if we punched the face out with a dotted line like a coupon, we could blow the cutouts from within. We who had been instructed in almost no science reasoned the idea would probably work, and set about stabbing a pattern into the widest side of El Hugé.

Cole made an incision near the stem with a shovel, standing on the mountainous pumpkin and flailing a little for his balance. When he had dug a hole, he motioned for the backpack.

Night had fallen for real and the butane perfume and flare of his Zippo were a shock in the cool air. He lit a handful of M-80s and thrust them down into El Hugé’s brainpan. He leapt off the top, rolling on the gravel. We ran and took shelter behind the pickup truck. We waited.

There is something in the soul of mediocrity that seeks to stomp down anyone or anything that stands out. There is something in us small-town kids that makes us lobsters, pulling each other back into a bucket so that no one gets out. We weren’t going to be outdone by a pumpkin. We weren’t going to outdo it, either. What could we do but destroy its beauty in the crudest, most fumbling form we could muster? We were children, and we were unremarkable and unloved. That beloved pumpkin had to die.

The explosion was muffled, yet sizeable. To our surprise, a neatly-punched face did not pop prettily free to reveal a jack-o’-lantern as tall as our shoulders. Instead, El Hugé collapsed, a giant hole at his top and another at his bottom. Hot seeds and guts rolled out along the underside, as if we had disemboweled an ungulate. The top was a mystery to us until flaming pumpkin chunks began to rain down, slapping into the black truck and coating us with hot, stinking gourd innards.

We were filthy and terrified, but we had won. No one ever found out what became of El Hugé; the papers remarked casually upon its theft, blaming the perennial scourge of teenagers. Years later, I went back to that riverbed and found a wide patch of stubborn, ugly pumpkins growing on surly vines.