Places Retreat

Wolf at the Door: Life on the Alaskan Frontier

“I hunt only for food. But, so do wolves—and my yard is a pantry. The chickens. The rabbits. The dog. Me.”

When the chickens in their scrap-wood henhouse squawk like a curb’s length of car alarms, I know something is in the yard—something that frightens them. I call them the Shirelles, a half dozen fancy bantams with feathers piled atop their heads like beehive hairdos. They do everything as a group, sashaying through the dirt, pecking at feed, clucking in harmony. Now they’re singing for their lives.

The noise rouses the border collie, who barks at the cabin door.

Let me out , he says. I have work to do.

As soon as I open it, he and his barking disappear into the night.

I live on three unkempt acres of meadow surrounded by the Alaskan wilderness, which yields a guide book of animal visitors each day. Moose pass through to wade in the pond or warm their cold moose asses against the heated glass walls of my greenhouse. Brown bears mine the gravel drive with steaming piles of berry-flecked shit. Eagles perch in the same spruce trees into whose branches the porcupines climb high to nap.

This is why I came here, a writer fleeing the Massachusetts suburbs in search of inspiration—and, in an admitted cliché, in search of myself—in a place bigger and wilder than any other I’d known. First to an island in the Southeast Alaska rainforest, where I ran my boat among the whale armadas, where the dog swam with sea lions and plucked decaying salmon from streams, where I watched a grizzly drag a snow-slick deer off a hunting buddy’s back. Then here, more north, more west, to this cabin at the edge of the world.

From my deck I can see mountain glaciers above the trees. At night the land soaks up the spilled ink of the Northern Lights. If I can’t find what I’m looking for here, in the startling quiet of these long, long winters, I’m not paying attention.

But now something has interrupted that quiet. The chickens have not stopped. When I hear the dog again, his distant barks grow louder and more frantic as he approaches. He’s moving quickly, his anger turned to terror.

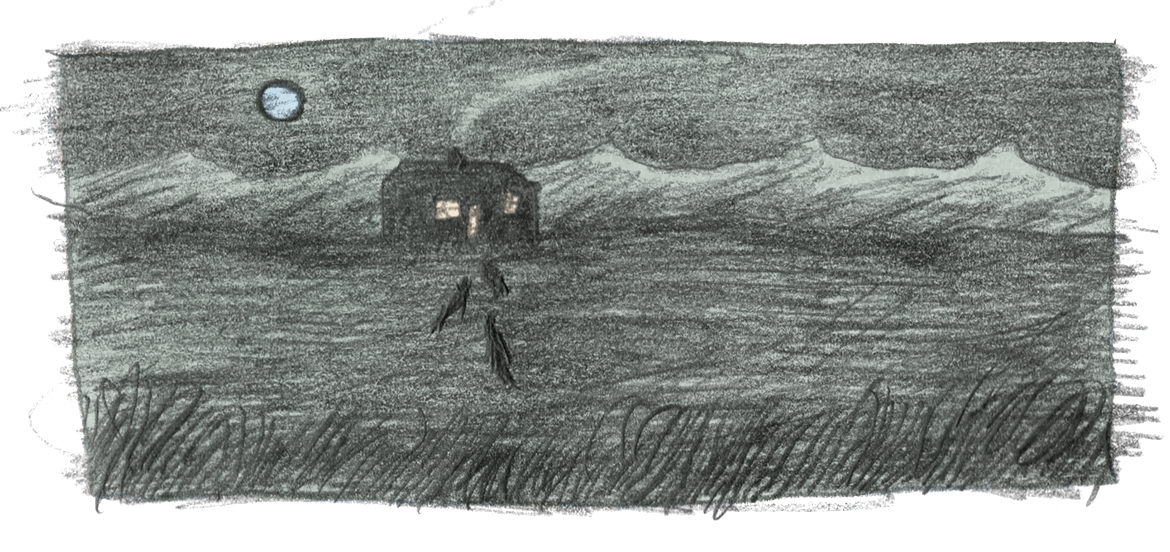

Let me in , he yells. No longer the predator, he appears out of the night, a frenzied ghost that mounts the stairs, crashes into my chest, and knocks me back into the cabin.

He’s terrified. He’s panting for breath. And he’s not alone. I’m back on my feet in an instant, slamming the door on the pack of snarling gray ghosts at his heels.

*

My father is an unsentimental storyteller, but when he remembers seeing a wolf while driving alone through western Canada, his joy is clear. She ran alongside his rental car for nearly a mile before vanishing into the trees that hemmed the road. The wolf allowed him a glimpse of herself, he says, a gift he still appreciates decades later.

This is how most people experience wilderness, in fleeting glances and unexpected intersections. Sustained relationships are increasingly rare—but they’re less rare here, in Alaska, where bears wander yards and roam the streets of town. The dog and I have run into them while jogging the trails that start behind the high school and end in residential neighborhoods. Animals use those trails for the same reason we do: It’s easier than bushwhacking a new path through the forest. We coexist tenuously, two worlds sharing a single planet.

I grab the shotgun, a weather-beaten 12-gauge, and the anxious dog circles me as I load it. He wears a bib of spit on his chest and a panicked expression on his face.

What are you going to do? he asks.

I don’t know , I say. What should I do?

Suddenly, he’s silent on the matter.

The wolves at the door are both hulking and sleek, possessed with an unsettling confidence. They hover like apparitions at the edge of the porch light. I pump the shotgun’s slide to load a shell into the chamber. I have no desire to shoot, only to scare and scatter. Though I’m a hunter, I hunt only for food. But, so do wolves—and my yard is a pantry. The chickens. The rabbits. The dog. Me. More than once I’ve stepped outside to piss in the snow and almost been trampled by moose.

That’s the price we pay for access to the wilderness—the wilderness gets the same access to us.

*

Where the paved road ends not far from my cabin, there’s a sign that warns:

TRAVEL BEYOND THIS POINT NOT RECOMMENDED. IF YOU MUST USE THIS ROAD, TELL SOMEONE WHERE YOU ARE GOING.

From there, the road itself—or something like it—continues with uncertainty into a wilderness where I spend as much time as I can. It’s placid, tranquil, and quiet. Which makes it completely at odds with the chaos of my life.

For two years, I’ve been editing the local newspaper in a town whose shine of natural beauty fails to hide the rampant alcoholism and domestic violence that rust it from within. The local custom is to pretend it does not exist. In towns this small, there’s a finite pool of people to choose your friends and neighbors from, your surgeons and plumbers and bartenders and car mechanics. Collectively, the town has a way of turning a blind eye to unbecoming behavior, but the newspaper editor does not. Which means that the man who beat his wife with a snowmobile jack—and whose trial coverage I plastered all over the front page—is also the dentist who performs my root canal. The job has become toxic, a poison I drink daily. At the same time, my relationship with my girlfriend—one born of fire—is now only flames. They consume all the oxygen and replace it with ash, leaving me to suffocate.

Each night I sit in my cabin, hunched over my desk, trying to write. It’s the only thing I’ve ever really wanted. It’s what I came here to do. It’s also a lifelong dream I have nothing to show for but enough rejections to wallpaper a floatplane hangar.

All the friends I might turn to for comfort? I left them behind in New England. My depression is deepening, and I’ve put a continent between me and everyone I love.

When winter came this year, the heavy snow turned my yard into a blank page that taunts my inability to write. The footprints of nocturnal wildlife are notes I try to read when the sun rises late each morning. The uneven penmanship renders their messages unclear, but I can guess what they say—the same thing all signs here say: Travel beyond this point not recommended.

*

Alaska’s a big place in which to try to find yourself. Maybe I never will. But to my surprise, I’ve found someone else. A few weeks after I left Massachusetts, a shirttail cousin told my father about an ancestor of ours who’d left home for Alaska a century before me. This cousin didn’t know anything more, and when we asked around the family, neither did anyone else. So I set out to research his life.

I learned that Captain Joe Bernard explored the Arctic for three decades. He spent eleven of those winters shipwrecked, frozen in, or presumed lost at sea. I found three obituaries for him in the New York Times archives. The papers would announce his death only for him to sail back into port a few years later. Unlike most of his peers in the age of Arctic exploration, Joe was self-taught, uneducated, and a free trader unsponsored by any government or other interest. Though he earned the respect of his contemporaries, and a measure of international fame, time relegated him to history’s footnotes.

Like me, he’d slung his dreams over his shoulder with his pack and coat and left home in search of something different. His dream was to sail a tiny schooner north of the continent, north of everything, to live off rifle and traps in one of the planet’s least hospitable places. All that he accomplished paled only against all that he survived.

Joe earned a name for himself the hard way—but when he did, it carried enough currency for the government to give it to a number of Alaska landmarks. Bernard Harbor. Bernard Island. Others. He’s buried here, too, as much a part of the landscape as the forests or the rivers or the rocky shoulders of the Brooks Range.

In comparison, my dream of writing seems modest. And I’ve found the inspiration I came here to seek—not in the wilderness, or the geography, or even the emptiness vast enough to swallow your self-awareness, but in the past. So why can’t I write?

Just like me, Joe wanted to leave his mark on the world. Unlike me, he did it in a very literal way, becoming so indistinguishable from the land he loved that you can find his name on the map. It’s my name, too. But a century later, even his own family had forgotten him.

What chance do I have?

*

Wolves leave tracks across the pages of Joe’s journals like paw prints in the snow. He trapped them for their pelts. He hunted them for their meat. In those long, Arctic winters, they howled outside his tent, as cold and hungry as he. When he found cubs nursing at the carcass of a mother killed in one of his traps, he raised them as pets, kept them in cages on the deck of his schooner and ran them with his dogs. The Banks Island tundra wolf, a white wolf with black-tipped hair along the ridge of its back and a limited range in the Arctic, was named Canis lupus bernardi , but it bore the common name “Bernard’s Wolf.” The species was named for Joe, who collected a number of them.

He occupied both worlds, human and wild. He moved between them until he belonged entirely to neither. When he left the Arctic, he tried to assimilate back into society and failed. He’d gone feral. And me? I’ve turned my back on my family, my home, everything comfortable and familiar to live here, where those worlds, human and wild, overlap. I also feel as if I belong to neither of them, but for all the wrong reasons.

Next to the chicken coop I built a rabbit hutch, and cages for quail. I bought fertilized duck eggs and hatched them under a desk lamp. The ducklings imprinted on me, following me around like yellow-robed cult members. The animals are food, but they’re company, too, an echo of civilization to fill the emptiness, tiny lives with which to share my own.

Coyotes ate the ducklings. The quail drowned. The rabbits were lost to a pair of great northern owls with talons as big as my hands.

I bought more rabbits. An eagle picked them off one by one, a sniper decimating my troops. I bought more still, and locked the doors to the coop and cages—keeping nature in, keeping nature out. A mink burrowed under the henhouse wall and turned it into an abattoir, painting it red with the blood of the entire brood.

Try again. Fail again. Fail better.

I bought plywood and laid a floor to keep the minks from digging their way in. A brown bear smashed down the wall, obliterating not just the chickens but their roosts, too, leaving a trail of feathered scat deep into the woods.

We can forestall it. We can curse it. Sometimes we can even change the circumstances. But we can’t change the outcome. Nature always prevails.

And now the wolves are at the door and they’re not going away. When I open it a crack, the cold rushes in. I can hear the Shirelles singing in their coop, clucking their fear. Maybe they’ve been studying their own ancestors, who lived in their henhouse before they did, and know how things ended for them .

The loyal dog stands at my side, frightened, but ready for whatever comes next.

In that moment, I know what Joe would tell me. He’d say that I’m looking at it wrong. He’d say that I’m the wolf at the door.

This is it , I realize. This is what I came here to find .

I nod at the dog. I throw open the door. I step outside into the night.