Places Migrations

How I Find Home in the Persian Poetry of Hafez

Home means that you’re anchored in something deeper than second-hand nostalgia, that you miss your country because it is a part of you.

As a young girl, I first discovered Hafez, the fourteenth-century Persian poet, in my father’s collection of cassette tapes. He had brought them to the United States from Iran, Mohammad Reza Shajarian’s music crackling in the car speakers, staticky from overuse. From the back seat, I’d watch my father in the rearview mirror, swaying his head to the sounds, his mouth stretched into a contented smile. I never understood the songs, but for a few words here and there. Nor did I know many of them were renditions of Hafez’s famous ghazals set to the rich tones of the hammered dulcimer and Shajarian’s smooth tenor.

As a teenager, I discovered Hafez again on my father’s bookshelf. Nestled in between a Quran and a book of du’as was a thick, leather-bound volume full of the poet’s beautiful verses. I used to pull the divan—his book of poetry—off the shelf just to feel the weight of it, as if I could absorb the words through my skin, if not through my eyes or my ears. My inability to understand Hafez’s ghazals, to recite them in the melodious and measured way my father often did, was the greatest failing, I believed, even then, of my American upbringing.

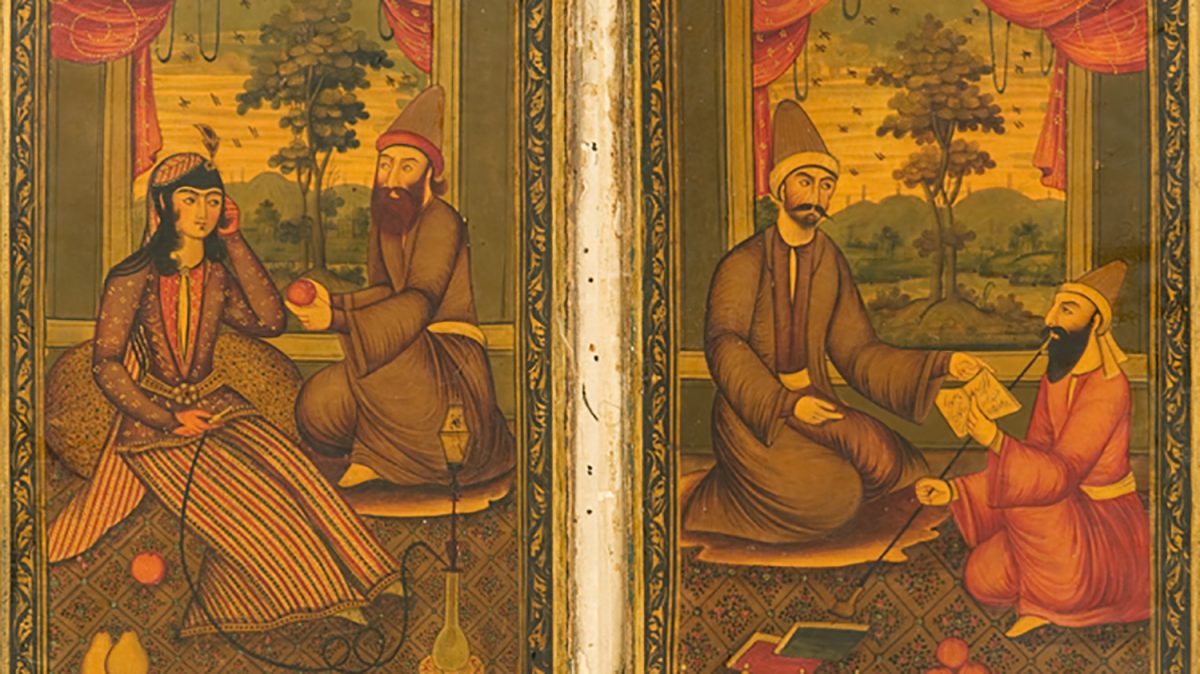

When I was a junior in college in 2007, I discovered Hafez once more in his native Shiraz, Iran, where he spent much of his life. My family and I visited the poet’s memorial site, a lush garden surrounding a small river on the northern edge of the city, not unlike the beautiful gardens featured prominently in his poetry. In tribute to Hafez’s memory, a marble tomb now sits beneath a striking pavillion, the dome in the shape of a dervish’s hat, an homage to Hafez’s sufism. It was late afternoon in August; the memorial site was sweltering and crowded. We pushed our way through the garden to the pavilion and stood beneath the dome, looking up at the intricate, colorful tile work on the ceiling. One by one, each member of my family laid a hand on the cold marble, etched with verses from Hafez’s poems. We stood in silence, the crowd around us evaporating into the hot air.

In my late twenties, I discovered Hafez yet again, on a Saturday afternoon in Washington, DC, after a friend sent me an advertisement for a class on his poetry near my apartment. The sessions were held in the home of an energetic and introspective Iranian woman. She felt Hafez everywhere, she said, and would use his verses as a means of understanding the world around her. She guided us, her mostly first-generation Iranian-American students, through the ghazals carefully, line by line, stopping briefly to explain the meaning of a word or phrase in English.

We took turns repeating the couplets, our voices often wavering out of fear that our pronunciations were insufficient. The other students would recite their portion of the poem, while I repeated the lines under my breath as practice. When it was my turn, I’d worry that my American accent—an accent my relatives have laughed at lovingly, but that I could never hear—masked the beauty of the words. It didn’t matter, the instructor reminded us when we hesitated; there was a little bit of Hafez in every Iranian.

That winter, for three hours each week, we submerged ourselves in Hafez’s ghazals, drawing parallels to our own lives. One afternoon, the instructor began the class by reading the first few lines of Hafez’s ghazal Lost Joseph , or Yusef-e gomgashte. She punctuated each couplet with a heady pause and I felt a familiar, yet unnamed truth begin to reveal itself to me.

In the poem, Hafez urges the reader or listener not to grieve, reminding us to be hopeful, even though home may feel inaccessible. Hafez draws on the Abrahamic story of Joseph, who was sold into slavery by his brothers, and appears to speak directly to Joseph’s father, who grieved his son’s loss for years.

Joseph, the lost, will return to Canaan, grieve not This house of sorrow will become a rose garden again, grieve not

Oh grieving heart, you will mend, do not despair This scattered mind of yours will return to calm, grieve not

When the spring of life sets again in the meadows A crown of flowers you will bear, singing bird, grieve not

یوسف گمگشته بازآید به کنعان غم مخور کلبه احزان شود روزی گلستان غم مخور

ای دل غمدیده حالت به شود دل بد مکن وین سر شوریده باز آید به سامان غم مخور

گر بهار عمر باشد باز بر تخت چمن چتر گل در سر کشی ای مرغ خوشخوان غم مخور

I felt transported back to the garden in Shiraz that hot afternoon, trailing behind as my cousins led the way to the car. I watched them huddled together, reciting their favorite verses in the same rhythm I recognized from my father’s Hafez readings. I tried to make sense of the sacred experience we all shared, of the emotion that brewed inside of me for reasons I could not name. But their words floated over to me, empty and unintelligible, hushed and cryptic like secrets.

There was a little bit of Hafez in every Iranian. I slowed down, allowing the space between us to expand, absentmindedly counting the birds in my path. They flew from tree to tree, from flower to flower, a group of them huddled beneath a large palm. I envied them in that moment, unrestricted as they were by language, borders, or governments; they floated above those hurdles, carefree.

When I read about Joseph, I recognized in him a homesickness for a country I have never truly known, the longing for extended family members who have always been strangers to me. I saw in his displacement my own. That unsteady feeling of being Iranian in America, caught between feuding parents forever on the brink of divorce. That cold reality that our existence in America—the roots of which can be traced back to US intervention, revolution, and war—has always been uncertain, constantly jeopardized by ever-changing politics and contentious foreign policy.

Grieve not.

Hafez’s repeated entreaties followed me long after I had left class that day. I recited the poem over and over in Persian, memorized it, relished the way the words demanded the use of my whole mouth, as if they carried a long-buried message that I could not, until that moment, fully discover and unearth.

I listened to the sound of my voice, amplified and bold, as I spoke certain phrases for the first time. But there was an insecure pretense in my delivery too, a timidity I recognized whenever I spoke Persian with my relatives. A sign of the quiet fear that came with claiming my identity, with claiming the words of Hafez as my home.

Gham makhor.

I paused, allowing the refrain to reverberate on my tongue.

Gham makhor.

*

Every Persian New Year, or Norooz, my father cradles the divan in his lap and asks us to think of a question. My questions over the years: Will baba let me go to the NSync concert? Will I win class president? Will I get the CNN internship? Will my boyfriend propose? When I nod at him, ready to hear my fortune, he cracks the book open. “Let’s ask Hafez for guidance,” he says.

The splendour of youth has again returned to the garden of spring

My father smiles. “Whatever you asked, the answer is a good one.”

This is how Hafez often comes and goes in my life. A line in a ghazal once a year and my meager attempt to remember it, to carry the meaning with me, in the months that follow.

It is often difficult to remember, to feel at home in his words. The last time I traveled to Iran was twelve years ago; Hafez’s tomb was one of the last places I visited with my relatives. With every day that passes, the prospect of going back to Iran becomes scarier, the reality of what I will encounter—older relatives, life under harsher sanctions, a new and unfamiliar sense of self—sinking deeper and deeper into the unknown.

Home may be perilous and the destination out of reach But there are no paths without an end, grieve not

“I don’t think I can go back,” I tell my Iranian-American friends, explaining that my work as a journalist, as well as my past activism, could put me at risk. They look at me pityingly and I shrug my shoulders. I pretend I don’t care because it’s easier than facing the truth: That I have not seen my family in over a decade. That they are banned from entering the United States. That my connection to them weakens every day.

“Don’t you miss home?” one friend asks.

Khaneh . I realize that I don’t know what the word means. I recall the obvious irony in the idea of going back—I’ve been told to go back so often that the phrase has become a parody of itself.

“Go back to where you came from,” a white woman shouted out of her car window when my mother and I were stuck in gridlock. I was thirteen. I’ll never forget the rage in her face, the way she spit the words out, her chin quivering as if she was about to cry. She locked eyes with my mother and didn’t let go. As soon as the traffic began to move, my mother raised her middle finger and hit the gas.

When I remind myself that I can’t go back, I am answering dozens of those hateful commands, even though I don’t mean to. And the injury is twofold. The words imply that America is not mine, though I was born and raised here. They suggest that I have a choice in the matter, that Iran awaits my return, if only I’d take her up on the date. The idea of returning home implies that I have a past there, a meaningful connection beyond flimsy childhood memories, beyond that dumbfounded wonder of being surrounded by people who look and speak like me. Home means that you’re anchored in something deeper than second-hand nostalgia, that you miss your country because it is a part of you. Years later, sometimes a familiar smell or sound—the unbearable odor of cigarette smoke on a hot day, the clean scent of freshly salted cucumbers, the gentle gurgling of water running through a fountain—will catch me off guard and remind me of that day in Shiraz.

Will I always feel like fragments of a whole?

In a state of absent loved ones and troubling foes God knows every sentence of your life, grieve not

*

Shortly after returning from Iran in 2007, I searched for Hafez in translations. I was twenty years old, still oblivious to the irony in turning to white Americans to serve as interpreters of my history and culture. At the bookstore near my college campus one afternoon, I was drawn to Daniel Ladinsky’s The Gift. I recognized the yellow cover; it consistently appeared at the top of my search results whenever I googled ‘Hafez translations.’

Will I always feel like fragments of a whole? In The Gift , I found passages I remembered, not from my father’s recitations or from Shajarian’s songs, but from the cheesy inspirational quote memes that were often shared on Facebook by mostly white yogaphiles and new age followers.

Many are familiar with what is probably Ladinsky’s most famous “translation”:

Even After All this time The sun never says to the Earth, “You owe me.” Look What happens With a love like that, It lights the whole sky.

Despite the fact that Ladinsky cannot read or write in Persian, he has published several translations of poetry, which he attributes to Hafez; The Gift , first published in 1999, is perhaps the most popular. I didn’t recognize any of the translations from my own personal experiences of listening to Hafez, nor were Ladinsky’s renditions written in Hafez’s traditional ghazal style, made up of about seven couplets, or beyts.

Still, I viewed the oversaturation of the quotes, plastered all over social media, as validation of Hafez’s genius, his ability to transcend cultures and languages. I cherished the translations as a window into the romantic life I naively envisioned for myself in Iran—where I’d have time with family, where I’d wake up to the voices of street vendors, where we’d celebrate the lesser-known Persian holidays we neglected in America. Ladinsky’s verses served as a blueprint to the beautiful things I lost when my parents left Iran.

Years after I first got The Gift , after leaving my Hafez class one afternoon, I searched for Joseph and his father in Ladinsky’s book. I craved a multi-lingual connection to the poem, a deeper relationship that would awaken my entire being. I think there was a part of me that recognized the tenuousness of my connection with Hafez, that it could break the second I left class, that I needed to protect it or it could wither and die.

Yusef-e gomgashte baaz ayad be Canaan, I repeated to myself as I flipped through the pages, gham makhor .

I couldn’t find him.

I soon learned that not a single one of Ladinsky’s poems resemble anything Hafez wrote in Persian.

“I feel my relationship to Hafiz defies reason,” Ladinsky writes in his preface to The Gift . He describes his work as “an attempt to do the impossible, to translate Light into words.” He speaks like one of those yogaphiles: “I had an astounding dream in which I saw Hafiz as an Infinite Fountaining Sun (I saw him as God), who sang hundreds of lines of his poetry to me in English, asking me to give that message to his ‘artists and seekers.’”

With this confession—that he saw Hafez in a dream—Ladinsky attributes his own work to a revered figure in Persian literature and culture, a figure much more prominent than himself, a figure that ultimately lends his poetry greater authority and influence. Indeed, without Hafez as its purveyor, Ladinsky’s work is juvenile and plainly derivative, a collection of haphazard inspirational platitudes.

Hafez came to Ladinsky in a dream, or so he tells us, and with this relative ease, he is able to claim the poet in a way I never have. For him, Hafez floats through the subconscious, he is boundless and free. For me, Hafez is lost in words I cannot understand, in air I cannot breathe.

What Ladinsky has done is cultural appropriation. It is, in the words of Omid Safi, director of Duke University’s Islamic Studies Center, a form of “ spiritual colonialism .” It is also painfully personal. In writing and publishing The Gift , in attributing his words to Hafez, he has taken advantage of an intellectual void within the Iranian diaspora—a diaspora that has been, for decades, detached from their home country, thanks to Western meddling that helped pave the way for revolution. The cold war that followed between America and Iran has shaped our lives, rendered our makeshift Iranian-American communities broken, left us longing for a past many of us don’t even remember. And we are incomplete, scrambling to make sense of our own history and culture, thousands of miles and centuries removed from the source.

It is this distance, this separation from home that has afforded Ladinsky the popularity he still enjoys among many first-generation Iranian-Americans. When I learned his poetry was a lie, I wondered if it was a deliberate betrayal, if he did it because he knew we didn’t know any better. I used to read his work and share it proudly with friends without realizing that his lies begot other lies—the ones I’d tell myself. That I knew who I was and my place in America, that the shallow sense of identity I felt was something tangible and real.

I hold on to what I can, to the phrases I know. Later, when I began learning to read Hafez, I thought about Ladinsky’s deception with an urgent, if not misplaced, existential panic. I wondered if he understood that we could be the last generation, that our families in Iran cannot come to America, that so many of us here cannot re-enter our homeland, that the threat of war seems to grow with each passing day. I wondered if he knew that, because of this, our culture could be easily forgotten, erased. I wondered if he intended to trick us into teaching his white man’s poetry to our American children, so that Hafez would live on as a sham. For our children, too, language won’t be a barrier or a factor into this translated ‘Light.’ The solution won’t be to learn Persian, but to lose it.

When my father recites Hafez, I often try to translate the ghazals on my own. My father will read a couplet, explain it in Persian, and I’ll respond with what I think is the English equivalent. The act is for my benefit only, a three-step imprinting process to ensure I won’t forget. My words are clunky, elementary, drained of emotion. They stumble and stammer their way out of me, the insecure battle cry of my Iranian-American generation.

In response, my father nods politely, and continues reading. I am grasping at the words that flow out of his mouth, so smooth and clear they slip through my fingers.

Gham makhor.

I hold on to what I can, to the phrases I know.

If the turning world does not move with our wishes today This feeling in time is not permanent, grieve not

I repeat the couplets, a halting prayer. The words gather inside of me like a burden, a promise I’ve made to myself that we won’t be erased. I parse through them carefully, taking refuge in my own interpretations. I wear them as a suit of armor.

Gham makhor.

I tell myself I am home.