Places On the Road

Walking Off Grief on the Appalachian Trail

Every hiker is called to the trail for a different reason, but we all share a common goal: We all want to finish.

What kind of trail starts at the top of a mountain? I thought to myself, panting and flushed from the effort of the first major climb. The schlep up didn’t even technically count toward the trail’s mileage.

“Idiot,” I said beneath my breath, unsure if I was referring to the trail planner or myself.

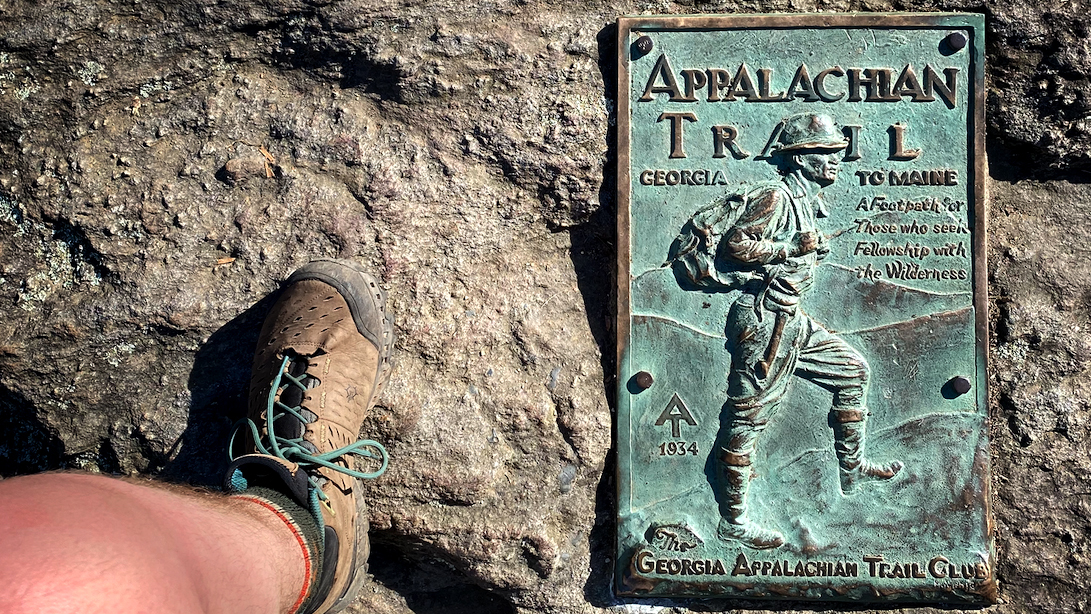

I bent over to touch the plaque at the Southern Terminus atop Springer Mountain in Georgia, officially beginning my journey along the Appalachian Trail. I kept quiet for a moment, eyes fixed on the horizon: looming, impending, unfamiliar. My knees quivered in my Sportiva hiking boots. It was too early in the year for the lush green I’d seen in photos and YouTube videos. Everything was still dead and brown. Dry leaves swirled around my feet and brushed against my calf hairs; I was twenty-three years old and a recent college grad who struggled to enter the workforce during a global pandemic. I wanted space and time to reflect, and the woods seemed like a fitting option. Now, I had a direction to walk: north. I inhaled, ready for the months of solitude ahead.

From behind me, a man said, “This is going to be the last cigarette I ever smoke.”

“Oh, really?” I turned around, surprised to see someone standing so close. “Good for you!” I wasn’t entirely optimistic about his prospects—or mine for that matter.

“Yep. Been smoking a pack a day for the last twenty years, but this one right here is my last. I can feel it.” His drag, audible despite the soft breeze, lasted a little too long. The silence between us lingered. I finally broke it and took my first steps.

“Well, I wish you the best of luck!” I yelled over my shoulder. “Maybe I’ll see you up the way.”

This man and I, a moment ago strangers, now shared something in common: We were two of the thousands of people in 2021 attempting to thru-hike the Appalachian Trail by traversing its entirety in a calendar year. According to historical stats, only one in four will succeed. The trail stretches for 2,193 miles, from northern Georgia to the middle of Maine, snaking its way through fourteen states in the eastern United States. Hikers cover anywhere from ten to forty miles per day, and the average thru-hike takes six months.

The conditions are brutal. During my five months on the trail, I encountered snow, straight winds, floods, heat waves, water shortages, black bears, and rattlesnakes. I showered once a week at most and hiked in the same damp, dirty, smelly clothes for stretches of up to two weeks before washing. On the ninetieth day while hiking through New York, I stripped completely naked in my tent and couldn’t even crawl into my sleeping bag because the heat rash was so painful. I laid atop it and cried myself to sleep. Among these tribulations, however, there remained a draw of the trail. It felt admirable to chase a “simpler” way of life.

“It’s just so cool that you’re doing this!” friends would message on Instagram. “It must be a life-changing experience!”

I’d read their messages sitting alone in my tent eating instant mashed potatoes for the hundredth night in a row while using a sewing needle and thread to slowly drip-drain the pus-filled blisters on my feet. I constantly found myself wondering, What’s the reward?

“Why are you even doing this, really?” my mom asked the day before I left, still unconvinced I would board a plane to Atlanta.

“I just want some space,” I mumbled, shoving my gear into my pack: camp stove, tent, lighter, water filter, food sack, sleeping pad, a set of camp clothes, titanium trowel, rain gear, sleeping bag, fleece pullover, a few Band-Aids, Chaco sandals, a Swiss Army knife, and a copy of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass : “A child said What is the grass? . . . I guess it must be the flag of my disposition, out of hopeful green / stuff woven.” Among the shiny, newly unboxed gear from REI, the only thing green was the titanium trowel used to dig catholes. Fully loaded, my pack weighed over thirty pounds, but I felt heavier. The truth was that the trail owed me something, for the chip on my shoulder that, even five years later, refused to budge. I was going to collect.

A week after our high school graduation, my best friend Alec and I led three of our friends on a four-day backpacking trip to Isle Royale National Park, a remote island in Lake Superior. It was grueling but amazing. We hiked during the day and stargazed at night, swam in the frigid June water, and roasted marshmallows by the campfire. We were eighteen and celebrating our adulthood, our independence, our self-reliance. I remember that, on our ferry ride back to the mainland, we sat next to an older couple, and the wife couldn’t believe our feat.

“I just think it’s so amazing you kids came out here all on your own. Such fearless youths we have today! Your parents must be so proud.” It was hard for us not to beam.

Once we got to land, we faced a seven-hour drive back down the North Shore toward Minneapolis. We planned to spend one last night at Temperance River State Park to break up the drive. It was my favorite place on earth; growing up, my family would swing by to take a dip in the river. There was an incredible spot where the water from the river, heated by the sun and rocks, collided with the near ice-cold lake water. You could straddle the line, one foot freezing while the other was warm. The trip wouldn’t be complete unless I showed this spot to my friends, to Alec. We set up our tent and headed to the river to swim.

The currents were stronger than I remembered, and in June the river hadn’t yet warmed under the sun. Alec got caught in a spot where the water cascades down a slope and empties into the lower pool—the “boil,” I’ve since learned it’s called. The spot where water presses downward instead of forward. It all happened so quickly. It felt like a matter of seconds. I stood, shouting on the opposed bank, twenty feet downstream, “Don’t fight it! Swim with the current!”

But it was too late. He sank beneath the surface. Alec. Who loved Arcade Fire. Who never turned in his homework. Who shaved his head with me in the eighth grade for a laugh. Who wrote music. Who spent summers biking around Minneapolis. Who was the most creative person I knew. Who loved vinyl records, Wes Anderson, and cooking with rendered duck fat. Who grew up with me. Who was my best friend. Who was drowning.

I saw a woman in a bright red raincoat call 911 from the bridge above. My world evaporated. My feet froze. Others jumped in to search for him. He was my best friend, and I didn’t jump back in. I collapsed. The next time I saw his face it was in a casket.

“Feel his hair,” his dad said. “It’s the only thing that still feels the same.” I looked at Alec’s swollen, waxy face. It took them three days to find his body in the river. Three days I spent hoping by some miracle he turned into a fish and swam into Lake Superior. I recoiled my hand.

“That’s okay.” It was hard enough just to look at him, dressed in the same navy suit he wore to the homecoming dance earlier that year.

Why are you even doing this, really?

The image seared in my mind, crystallized like the fat on a steak — bubbling, taunting, pungent — the boil. I needed to swim with the current.

Every hiker is called to the trail for a different reason: to process grief, to conquer a physical challenge, to curtail corporate burnout, to connect with nature, to mitigate a midlife crisis, etc. Everyone I bumped into had a unique story, and usually they weren’t shy to share it. I met recovering addicts, depressed divorcées, college dropouts, Amish defectors, newlyweds, retired dentists, veterans, and even a day trader who spent dusk at camp hunting for cell signal to check their portfolio’s performance. Thru-hikers comprise a wide array of hopefuls, but we all share a common goal: We all want to finish.

Thru-hikers comprise a wide array of hopefuls, but we all share a common goal: We all want to finish. Every thru-hiker knows that the first true test of grit is the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, a little over 150 miles north of the Southern Terminus. The trail is remote, there are virtually zero places to bail, and the elevation is magnified. It’s the first true make-or-break moment of the hike. For many, it’s their end. It was in the Smoky Mountains that I met a hiker who’d impact my own journey. It began, as so many conversations between hikers do, about her trail name.

“How’d you get the name Rebound?” I asked.

“Have you read Wild ?” she countered. Of course I had. Nearly everyone on the trail had. Some people loved Cheryl Strayed, some disliked her, but virtually everyone knew of her. The memoir of her thousand-mile hike on the Pacific Crest Trail to overcome grief became an international bestseller and even spawned a movie adaptation starring Reese Witherspoon. She was as close as a long-distance hiker could get to being a household name. Rebound loved her, and she had good reason to.

“My mom passed away a few months ago. I’m out here figuring things out but also to honor her.” As she spoke, I nodded in understanding. “It’s a really difficult journey, but I know she’d be happy for me. I spend more time out here smiling than crying. This is my rebound.”

I never saw Rebound after the Smokies, but we exchanged numbers and I texted her a few days after our parting. I told her my story and ended it with this: I know these things are super hard to talk about, but I’m glad us Cheryls have a way of finding each other!

That’s when I knew I would finish the Appalachian Trail. It was no longer a question of if, but when—no matter how many tuna packets, mountains, rattlesnakes, blisters, or shits in the woods it took. I was going to see this hike through. Not in penance, and not in vain; I was going to hike for joy.

It wasn’t always easy. The Appalachian Trail is known for its constant flux in elevation, and those who complete the trail hike the equivalent of summiting Mount Everest sixteen times. I still faced four more months of tough terrain. On day forty-five, I hiked up Chestnut Knob. It was the day I peeled palm-size strips of skin off the backs of my heels. I was breaking in new boots, and the pain was excruciating.

“Fuuuuuuck!” I yelled into the woods, and I collapsed between my trekking poles. Sobbing into the pit of my elbow, I recalled holding the pieces of skin in my hand earlier that day. I rolled them into tiny little balls between my index finger and thumb and buried them in the dirt like two little corpses. Every place on my feet was rubbed raw, except for the place I wanted to erase, my right instep—where my tattoo was.

“I got a tattoo to remember Alec,” I said, slipping my foot out of my sandal. His mom looked at it briefly but then returned her gaze to the night sky. I never thought I’d get a tattoo, but when someone you love dies at the age of eighteen, it seems like an adult way to memorialize them.

I could never

12-13-97

“It only has his birthday. I didn’t want to add the other date. I got it to remind myself to push beyond my comfort zone. To catch myself before I said ‘I could never’ do something.”

Her eyes stayed toward the sky. What I told her was a lie. I got the tattoo because of something she said a week earlier: “I just feel like you’re going to forget him.”

Her words stung. She was grieving, harder than any of us—she’d lost her son—but it hurt. I stayed quiet. I thought to myself, I could never . The tattoo was my silent promise to her. Five years later, I wanted to take it back.

“I’ll never forget!” I shouted into the woods. “I don’t need a fucking reminder! That day’s been on my mind for the past five fucking years, and I’m tired of it!” I was yelling at everything: pine cones, trees, rocks, squirrels, the trail, myself. “I hate this goddamn motherfuckin’ tattoo.” It didn’t remind me of Alec. It reminded me of his death. I hiked on.

I hiked on for another hundred days.

By that point, I had long ditched Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and had replenished my precious one-book allotment with a copy of Emily Dickinson’s Final Harvest . One poem became my motto:

The hallowing of Pain Like hallowing of Heaven, Obtains at a corporeal cost— The Summit is not given To Him who strives severe At middle of the Hill— But He who has achieved the Top— All—is the price of All—

I reached the summit of Mount Katahdin in Maine, the Northern Terminus of the trail, on August 1, 2021. All I could say was, “Wow.” Like some gritty, delirious Owen Wilson, I said it over and over into the clear blue sky. “Wow.”

I was slimmer, stinkier, and bespeckled with patchy facial hair. But I was also the same. I finished the trail and, though I still missed (still miss ) Alec, I finished grieving him. For me, to “finish” grieving meant making a choice. So many of my choices since his death were rooted in penance and shame: guilt for planning our hiking trip to Isle Royale, for swimming in Temperance River, for not jumping back in. Finishing grieving meant finally choosing to forgive myself and to celebrate, rather than mourn, his life. Those 144 days taught me to carry only the things I needed most and to leave behind what weighed me down.

Finishing grieving meant finally choosing to forgive myself and to celebrate, rather than mourn, his life. I never saw the man who smoked his “last cigarette” atop Springer Mountain again. I’m not sure if he finished the trail, but I rooted for him—that’s what the community does . Life isn’t “simpler” on the trail, but it is different. Kindness prevails. Thru-hikers share duct tape, water filters, food, stories, anything that might help. The trail provides time for reflection and space for Cheryls to connect with other Cheryls walking off their grief. I surrendered to the discomfort, the pain, and the current to move forward. My legs ached, my feet were destroyed, but my smile was wide.

What’s the reward?

It’d be too simple to say my grief ended by hiking, but the trail was an unflinching lesson in humility and beauty. Smiling was one of the hardest things to do after Alec died. Each upturned corner felt like a betrayal to my sadness, to his memory. On the trail, I smiled a lot, and there, atop Mount Katahdin, my smile was unapologetic. I’d still carry his sense of humor, his kindness, his creativity, but I’d let go of the trauma, pain, and guilt.

Another truth about backpacking: It involves a daily routine of unpacking and repacking. I still struggle when the loss hits particularly hard—on his birthday, the anniversary of his death. On those days I try to surround myself with friends, old and new, and share happy memories of Alec: midnight grilled cheeses by the campfire, skiing in Lutsen, when he starred as Aladdin in our junior high’s theater production, stargazing on Isle Royale.

And then it comes again, that big, toothy, grown-up smile, the kind that oozes gratitude. One that’s paid, step by step, the price of All . I finally knew what it was worth.