On Writing Debut

Writing the Canon of Now

“Our stories are like a glittering, infinitely faceted gem.”

This is Debut, Tanwi Nandini Islam’s monthly behind-the-scenes look at being a first-time novelist. Islam has previously written about creating the perfect cover for her first novel .

*

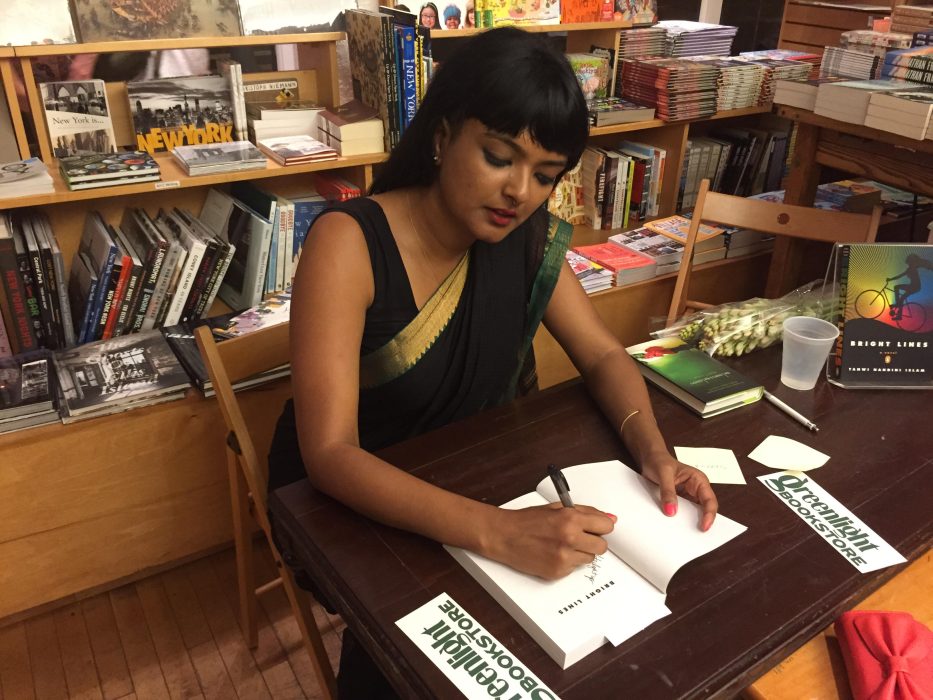

On the night of my book launch at Greenlight Bookstore in Brooklyn, my conversation partner Mira Jacob and I both braved the August swelter in saris. As far as attire goes, it doubles as beautiful and suited to hot weather, but the choice was intentional. I wanted the two of us—friends and South Asian diasporic women writers—to wear clothes that made no secret of our lineage. The room brimmed with the love and anticipation of people I’d known in different eras of my life. I’d been in hibernation, exhausted from stress, leading up to my debut. After years of obscurity, hard work, and numerous, disparate hustles, here I was, ready. And there they all were, waiting to hear me read from a book that had existed only as an idea, until now. Now, it no longer only belonged to me. It was theirs, too. It belonged to anyone who decided to read it.

One question, posed by a Black writer friend, resonated with me. He asked, “We’re in very violent times right now. What do you think our work must do in this moment? What do you think your work does?”

I answered this in the only way I knew to be true: “We must do everything we can to reimagine the worlds we live in, examine our histories as they influence the present. My thing is: I can’t be free unless you are free, too. And all of us writers of color that seek to do this work—we’re building a new canon. We’re building new ways of being free. We’re creating the canon of now.”

The phrase “canon of now” was a spontaneous, visceral reaction to his question. On one hand, I mean quite literally the work of writers of color, immigrant writers, of women writers, of trans writers, queer writers—any writer who exists outside of dominant white, Western culture. On the other hand, I mean the polyrhythmic, democratic forms writing takes in the present-day age of the Internet: essays, blogs, texts, chats, statuses, tweets. Every day on the Internet, words are written and forgotten and rewritten. The beauty is that there’s no monolithic voice or last word; it is always a shifting conversation, a chorus of many.

While my friend posed his question out of love and respect, I knew that I’d need to prepare myself for the discomfort of answering strangers’ questions in subsequent readings during my tour of the U.S. At a reading in a Berkeley bookstore, a question posed by an Asian-American audience member, someone I’d worked with virtually, but had never met in real life, made me realize that there’s a certain ennui when it comes to fiction about the experience of immigrants and second-generation Americans.

“We’re familiar with stories by Asian writers—you know, a family story, a return home to their country of origin. How is your novel doing anything different?”

“The work of fiction is to illuminate; our stories are like a glittering, infinitely faceted gem,” I replied, aware that I felt vaguely offended by the question. “There will never be anyone else who can tell my side of a particular story, no matter how many times we think it’s been done before.”

I knew the questioner shared my experience, by virtue of our hyphenated Asian-American identity. And I often pose this same question when I’m watching television or film: Why can’t people of color live nuanced, complex lives? Why can’t we just eat, pray, love? Does everything have to depict well-worn tropes of arranged marriage, honor killing, strict parents, slavery? Why must we suffer?

It’s not just boredom coming from Asian-American readers; the heyday of Indian-American literature is considered a relic of the near past. There are readers and some editors who believe that because they’ve read Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children , Jhumpa Lahiri’s Interpreter of Maladies and Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things back in the 1990s, so they know all about Indian stories. Every one of my South Asian writer friends have been confronted at some time or another about our authenticity—where do you get the right to tell this story? Aren’t you tired of sad, depressing topics like war and bloodshed? The fallacy of this type of thinking lies in the myth that if you know one story, you know them all. I reject the notion that one well-known book’s narrative taints all other books from a general region. These are novels, not contagion.

Bright Lines is the way I imagine a lovingly dysfunctional family, their community, their history, their secrets—people who live between worlds, never quite grounded in any place, physically and psychically. I wrote a coming-of-age story of queer, brown, young (and middle-aged) Bangladeshi, Muslim characters. I’m fascinated by the relationships between dominant and indigenous cultures, and how the oppressor and oppressed swap masks depending on context. So, when we’re asked to justify our stories, I wonder: Is it too hard to picture a fictive story set in the United States without any significant white characters? Moreover, is it too hard to imagine brown people in, say, ten thousand books, all doing different things and the same things, because they’re human?

“Lately, I’ve been questioning the whole notion of the canon,” says Mira Jacob . “It ’ s not just that the stories included aren ’ t ever about people like me. It ’ s that when people like me do show up, we are footnotes, one-dimensional bit players, only there to embellish the real story. The canon lives in and around and all over me.”

Jacob recalls a moment during her tour for her debut novel, The Sleepwalker’s Guide to Dancing . “An older Indian auntie asked me, ‘Why do Indian authors always write about Indians? When do you think we will start writing about real things?’

“ I want to tell you that I said something brilliant at that moment,” says Jacob, “but the truth is, it took my breath away. Sometimes I worry that some of what that auntie had—that deep, internalized colonization, that thing that tells you your own story is unimportant—lives in me, too. And that ’ s what I think about when I sit down to write. I think, ‘Let ’ s make the canon of now.’”

In high school, I loved Catcher in the Rye and Jane Eyre. (I liked Wide Sargasso Sea more.) I reveled in how different those novels were from my world. Like most young people across the United States, whenever I read fiction or plays, I read the white Western canon, mostly men, with a woman or two for good measure. I’d never been assigned to read work by writers of color, until the Autobiography of Malcolm X. And that was the first time I’d made a connection between Muslim life and Black American history. It set me on a course to discover the work of Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, Toni Cade Bambara, and Maya Angelou: Black writers who shaped American literature in powerful, innumerable ways.

A few years later, I would read a novel in English with Bangladeshi-British main characters: Zadie Smith’s White Teeth. These first- and second-generation characters exist in a comedic, often chaotic world. It’s a riotous book with a cast of multidimensional, multicultural characters, a book of collisions between people brought together by everyday, and sometimes extraordinary, circumstances. Looking back at this experience of reading Smith’s debut, I realize that Smith’s protagonist Samad Miah Iqbal, and my Anwar Saleem, are brothers cut from the same diasporic cloth.

Before White Teeth , I’d never thought about my omission from literature before.

“On some level I still write for the reader I was when I was younger,” says Mia Alvar, author of the debut short story collection In the Country, “ searching for my face and my family’s experience in literature and only rarely finding it.” In the Country is a stirring collection of stories, all lyrical, transnational portraits of the Filipino diaspora. However, Mia is not writing for an audience when she’s crafting her stories. “I don’t believe that every reader has to ‘get’ every cultural detail I write; I’ve felt alienated and disoriented by books set in worlds unfamiliar to me before, and that’s okay. I like it.”

Ultimately, Bright Lines is what I wrote after twenty years spent reading without encountering a single Bangladeshi-American-Muslim-queer-girl character. I wrote what I’ve yearned to read my entire life. It’s messy, uncomfortable work to write what you didn’t have as a kid, to write without worrying your work won’t be understood. So, when I’m posed a question like, “How are you doing anything different?” I’m glad for it. The question—no matter how offended or uncomfortable I feel—is valid.

As a debut author, I am paying homage to the ones who’ve come before me. Simultaneously, I’m charting the choppy waters of an untold version. There is always another point of view, a parallel space-time, a kindred text. I’ve come to understand that originality is a conceit that’s as true as it is false, possible and impossible. All writers retell the same myths about love, family, betrayal, secrets, death, sex and war and revolution. Retelling is the work we’ve taken on. Yet, in the canon of now, writers of color continue to re write a legacy of invisibility, work braved by many writers before us. We’re writing our existence out of the sidelines of literature to the forefront. We’re writing and rewriting our stories, for they are infinite.

Tanwi Nandini Islam’s fiction-writing workshop begins on May 30. Apply now .