Swimming in a glass of water

The bittersweet struggle of living and the dignity of pain.

The bittersweet struggle of living and the dignity of pain.

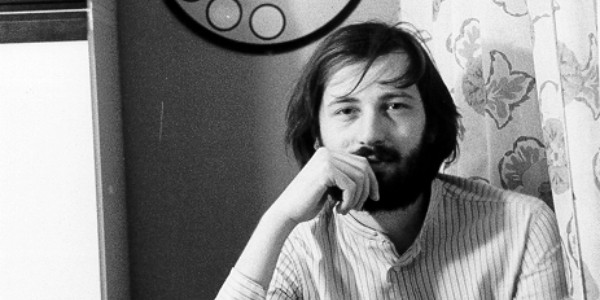

25 years ago Pier Vittorio Tondelli died. He was 36, he was a writer, a poet, a critic and essayist, an extraordinary human being. He was honest, thorough, restless and deep.

He was also homosexual, and queer; he embraced all the possible meanings of it, with pride, confusion, curiosity, desire, awkwardness, proximity and distance, sometimes joy, strenght and pain, unimaginable pain. Love, life, relationships were often excruciating for Tondelli, and his strong and immediately recognisable style returns to us all the rich and multifaceted spectrum of his perspective and emotions.

I was 19 the first time I came through one of his works.

Altri Libertini, his first collection of short stories, published in the 70s, was a cult for generations of weird, lonely and brave travellers. His first colletion was a chronicle of real life: drug addicts, dives, dirty toilets, train stations and people constantly living on the edge. I was nothing like that at the time; again, the wild and true part of my identity was about to flourish. That day I was just a frightened little girl on a train, but I could feel it, marked into my bones, the foetus of a person, the person I wanted to release.

It was love at first sight. Not even that, it wasn’t about the sight, it was about language, the words, the commas and the full stops. It was about the silence in between. It was on a Intercity train travelling from Sanremo, the tiny and boring city where I was born and Pavia, another tiny, cozy and foggy city in the north of Italy. Pavia would have become the place of my heart and my most precious memories, but I didn’t know that yet. By then I was just meeting the voice of my late teens, I was encountering the poet who sang my anguish and insecurity, I was finding the sound of my transition from a world I knew and the unknown. the responsibilities of an adulthood I wasn’t ready to face.

I’ve read Pao Pao, Rimini, Biglietti agli Amici, everything I could find, and it didn’t matter if I was reading fiction or non fiction, I could feel that sense of belonging and connection: Tondelli wasn’t telling my story, he wasn’t talking about my times and places. But he was able to talk about feelings and people like no one else I’ve read before. The masterful writer’s true gift is the ability to tell a story and many stories and all the stories, to talk to a specific audience and everybody.

I haven’t experienced the turmoil of the 70s and 80s in Italy, it’s couldron of art, politics, fashion and riots, new narratives and heroes, dangers and culture, but I was experiencing fear and insecurity, I was experiencing the void of a generation, the trouble of becoming an adult. I was experiencing love and disillusion, friendship and loss, I was feeling invincible one moment and completely beaten the next one.

And Pier Vittorio Tondelli spoke to me and many other people in Italy, picturing the past but tailoring the present and the future, their shades and richness, contraddictions and fabrics.

Tondelli was a gifted storyteller, with a rich and complex style and a clear vision, but for me, first of all, he was an extraordinary writer, able to restore the dignity of pain through the most powerful gift of literature: its complexity and empathy. There’s never pity in his words. Not a refuse of self-indulgence or compliacy.

There’s always the participatory process of sharing pain, embracing pain and narrate pain in its deepest meanings and implication in he’s writing. Pain isn’t something to dread, but a legitimate experience of the human soul, a revealing aspect of the everyday life and a precious wound to welcome, understand, process and turn into a gift. Not in the self-pitying vision of the Catholic Church (even if that aspect was undoubtedly evident in he’s body of works) but in the genuine and sometimes fallible tenderness of an emphatetic human being.

There is dignity in pain, in suffering, in the ability to embrace those feelings and tell stories. There is dignity in mourning and suffering, in loneliness and silence. There is power in a defeat and there’s growth in capitulation.

Camere Separate, his last novel, (Private Rooms, the only one translated into english by Simon Pleasance) is not simply a story of love and loss, it’s the portrait of the richness of humanity, the multifaceted nature of relationships and intimacy. Tondelli explored the deep and complex universe behind the idea of love and belonging. Through the story of a man who travels through the most traumatic experience of his life after he loses his partner, Tondelli explores the true meaning of life, of giving up and find each other again, at the end of the long struggle of mourning our losses. Shock and pain are not simply human feelings, they are social and political experiences, literary experiences, collective experience, and because of the ability to share and build stories, we can discover (and rediscover) the generative power of losing and suffering.

Pier Vittorio Tondelli whispered to me that there was greatness in my insecurity and value in my fear, he taught me that all the mess I thought it was something to hide, it was precious, it was mine to experience and mine to embrace, to live and to tell. Mine and entirely mine, something I could relate to and turn into a story. My story. Our story. Your story.

Maybe love can last forever, certainly mine for Pier Vittorio Tondelli will.

Ciao, Pier Vittorio, I miss you every day.