Swimming in a glass of water

A Collective Excuse for Individual Ignorance

A Collective Excuse for Individual Ignorance

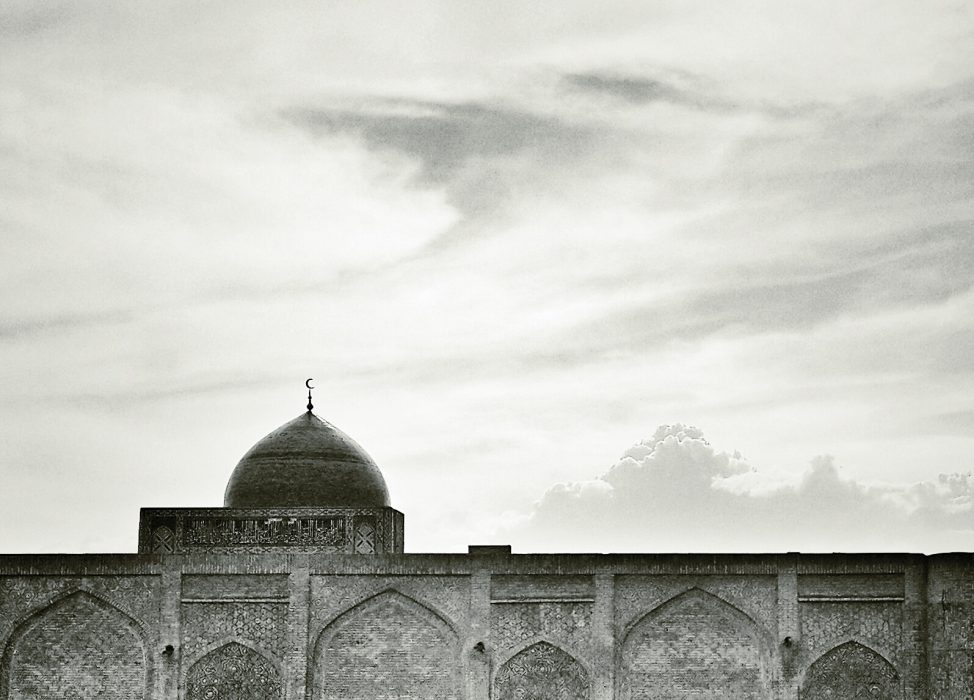

On Friday afternoon I exited the mosque with my closest friend and walked right into a look of disgust aimed at me. This is one of the two reactions I get when people see me leaving the mosque with my friend. The other reaction is that I am completely invisible due to my headscarf-wearing friend (one of the privileges of being a white Muslim).

You see, no one would ever assume that I’m a Muslim. I don’t “look Muslim” as people like to inform me when expressing their shock over the fact that I’ve converted. I’m white, I’m a woman that doesn’t dress modestly or cover my hair, and my American name rolls easily off the tongue. The only thing people ever assume when they see me is that I’m gay (and to their credit, they assume correctly). I converted to Islam after many discussions with my friend about the faith and found that its most important core beliefs and teachings are beliefs I’d held most of my life, even as someone that had been an atheist for as long as I’d been capable of independent thought. Converting to any religion had never been something I imagined I’d do. I wasn’t raised in any faith, and my only exposure to religion was the various forms of Christianity, and that had always been an overwhelmingly negative experience for me. I once had a teacher whom I adored and looked up to. She was so open minded and welcoming to all kinds of different people. Yet when I confided in her that I thought I was gay, at just thirteen years old, she didn’t have a warm, open response for me. Instead, she told me she’d pray for me, pray that I’d see I wasn’t living as God intended and mend my ways. At that time, in my young mind, she represented not just all Christians, but all religious people. This was when I learned the difference between tolerance and acceptance, and this was what turned me off from religion as a whole.

Imagine my surprise when, sixteen years later, I met the person that I would end up having more in common with than anyone I’d met before, and she was a headscarf wearing, halal eating, five-times-a-day praying Muslim. I was a freshman in college when 9/11 happened and before then, the only thing I knew about Muslims, having grown up in Michigan, was that they all lived in Dearborn. I never bought into the all Muslims are evil terrorists line of thinking, but only because I knew I didn’t appreciate it when people assumed all homosexuals were horrible pedophiles, not because I knew anything about the faith or its followers. It wasn’t something I gave much thought and because of that, I’m ashamed to say that subconsciously, Muslims had become other and I assumed they would hate everything about me and my life. Since converting, though, my experience has been the opposite. Not one Muslim I’ve met has taken issue with the fact that I’m gay or shamed me for how I dress or any number of crazy things people believe Muslims stand firm against. Since converting, my feelings toward all religions have changed dramatically. Since converting, I’ve seen how hypocritical and wrong my previously held belief that all Christians are just as terrible as that teacher I had. One person’s interpretation of their religion can never be trusted to be representative of every member of the faith.

have

More and more, as the country becomes more polarized, I see people relying on a couple standard catch-phrases that they use to try and rationalize their feelings when really all they’re doing is excusing xenophobia. Those two lines are:

“We’re afraid because you can’t tell who’s good and who isn’t.”

“People have a right to be afraid, 9/11 changed us.”

The first one, that’s true for anybody. You never really can tell who is out to hurt you and who isn’t. But when people say that line, they’re not speaking of people in general, they’re not constantly afraid as they walk down the street, wondering which young white man is carrying an assault rifle en route to his planned attack. No, they’re afraid of Muslims (or people they assume to be Muslims), and they’re not so much afraid as they are choosing to remain ignorant. And that’s their right, go ahead and be afraid of whoever you want, but don’t blame it on anyone but yourself, and don’t ever say “we” because “we” aren’t afraid, you are.

The second line, it’s pretty much the same thing. Yes, 9/11 changed America, but so has every mass shooting and the people that claim fear is their reason for intolerance certainly aren’t meeting all young white men with the same fear. What 9/11 did not do was change America in such a way that warrants irrational fear, because once again, the people that claim this aren’t living in fear of every single race and religion that has ever committed mass violence. Instead, they use “fear” as their word for choosing to remain ignorant. Americans have no more of a right to be afraid of every Muslim than every Muslim has to fear all Americans. And let’s not forget that the two aren’t mutually exclusive. There are many Muslim Americans (about 3.3 million according to Pew Research Center).

Every time I hear one of the aforementioned excuses, I feel a bit sick because people are using their own personal ignorance and xenophobia and attaching it to every American (or at least every American that looks like they do) and using it to further spread this feeling of intolerance and hate that some politicians are encouraging. It’s not an issue of fear. It’s an issue of intolerance and ignorance, and people want to make it a collective issue so they can feel a little better about themselves. Yes, 9/11 changed America forever, but it was fifteen years ago, and we live in an age of technology that allows people to get to know just about anyone from any race, religion, and culture they wish to. It’s simply a matter of whether or not people are going to take advantage of that. And if they choose not to, that’s on them. Because there is no we.