Shroud

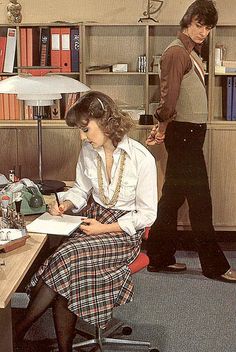

Knees to be patted, palpable lascivious tension and buckets of disinfected sawdust at the ready in the boiler room…

Knees to be patted, palpable lascivious tension and buckets of disinfected sawdust at the ready in the boiler room…

Susan Gedthorpe always tucked her polythene carrier bag behind her legs when sitting on the bus. It felt safe there and she didn’t like resting it on her thighs; not because it might crease her skirt – she mainly wore pleated skirts and they were permanently pressed so that she could safely fold them in a suitcase – but because she disliked the thought of the bottom of the bag shedding grime from the floor onto her lap.

With her for the rest of the day might be traces of dandruff, cigarette ash, even she thought, curling up her toes, dogs’ muck. And after all, she usually ate her sandwiches from her lap.

It wasn’t that it was frowned upon to eat at your desk. Far from it. Jackie Nelson had no hesitation in eating lamb kebabs on hers with the all the chopped onion and cucumber flying out when she took a bite and landing in the out-tray, with letters ready for signature. It was just easier to keep an eye on the corridor and whip back the lid of her lunchbox if any of the sales managers should glance in on their way to the canteen.

If she kept her eyes down and pretended to shuffle some work around on her desk, with luck they passed by. But once she had been caught halfway through a cheese and tomato sandwich which they had seemed to take as some kind of cue to wander in and sit nonchalantly on the edge of her desk, knocking her miniature fuchsia against the wall so that the last three blooms that had lasted a full two weeks, fell off and lodged behind the roller on the typewriter.

“Hi Suze, how’s it going?” Tony Malpass had said picking up the framed picture of her sister sitting on the end of a see-saw with her skirt rucked up. “Hey, Dave, take a look at this.”

Dave Broadbent was quite short, only about an inch taller than herself and didn’t seem to smirk so much. Sometimes if he met her in the lift he would strike up a conversation about the overcrowding in the car-park or the smell of cooked brussels sprouts that wafted up the shaft from the kitchens.

Susan didn’t really mind them making remarks about her elder sister. She had always thought that picture had summed her up rather well, showing off her legs like that and tilting her head back as if she was a model.

Diana (from the age of 10 she begged everyone to call her Diana rather than Daphne) had insisted on her last brief visit from Weston-Super-Mare that the see-saw picture was nicer to keep than the one of her hugging her neighbour’s collie and had hurriedly shoved the rest back in her handbag. But then, Diana was braver with men, no question about that.

When she was whistled at in the street she would actually look round and smile and sometimes even answer back. “Don’t be so rude” she would shout through giggles at a bronzed torso perched on scaffolding fifteen floors up.

Susan always kept her eyes on the pavement and with luck they would move on to some else. Her skirts weren’t short enough, she consoled herself, for them to bother with her for long. No, Diana was fair game for comment. But Tony Malpass didn’t leave it at that. He would start pumping her for information about her boss Eric whom they had seized upon as a constant source of amusement ever since he took to wearing sandals and socks during the summer.

Eric Searle was on the whole easy enough to work for. A bit pernickety perhaps – he always insisted on a cup and saucer for his tea instead of a mug and frowned if she gave him the chipped one by mistake. But as for the work, well, he was very slow at this side of things so stuff to be typed came irregularly and not much of it at that. He would sometimes sit looking out of the window for long periods. He was single too and she supposed lonely, although as far as she could determine he was busier than herself, what with his Scrabble club of which he was now vice-Chairman. But she felt he stayed at work as long as he dared without it looking odd; as if his office – barely furnished with a couple of spider plants and a picture of a ship in a storm, was friendlier than home. However, despite his long hours, some weeks she might go two days without even a memo, which left lots of time to tidy her drawers. Time to put all the drawing pins she never used (but thought might come in handy at Christmas to pin up cards) back into one of the tiny compartments in the slide-out pencil tray. They always spilled every time she shut the drawer. But the sliding tray that had come with the new wooden desk last year was such a sophistication after the metal one with sharp edges, that she felt she must use every little bit of it. There was a lot of desktop paraphernalia you could tidy away even if you weren’t quite sure when you’d need it – pins, needle and thread, foreign stamps, odd staples that sort of thing.

Eric wasn’t very neat. She did call him Eric now. It had been difficult at first but he had insisted at last year’s office party that it was time to start calling each other by their first names. She had offered to put things in order once a week for him. And they had tried that Friday afternoon after he’d made a mess dunking his custard creams and dropped soggy biscuit inside his top drawer. But she had only managed as far as removing everything (which took a while because the bottom of the hole puncher fell off and shed white circles everywhere and there was a mouldy tangerine stuck to the drawer lining) when he murmured something about putting it all back himself so he’d know where to find it.

When she peeped a week or so later he hadn’t moved the tangerine but laid his Handy Pack of tissues over it, next to his pocket chess set, which she sometimes caught him playing just after lunch.

It was the time of year for tangerines. And satsumas of course. They weren’t quite as juicy or sweet but less messy as there was always a gap between the peel and segments so you didn’t have to wash your hands afterwards. Madge said she preferred not to wash hers as it made her hands smell nice all day. But then her keyboard was always sticky. She never used the sachets of disposable typewriter cleaners that the serviceman left.

You could get a ‘bag a sats’ (as the smallholder would call them) from the stall on the corner of Rupert Street opposite Prettyprint the stationers. A dumpy girl in a short paisley shiny skirt – made of the same material as wipe-easy tablecloths – had spent the last two days dressing the windows for Christmas. It was 3rd November but Eric said you may as well get some glitter up as early as possible as even a filing tray looked more exciting with a bauble hanging off it and they might sell a bit more before the sale.

The talk of the office was the Christmas Party, to be held in the Crown Hotel’s banqueting suite – instead of down in the canteen like last year. The rumour was that the reason why the management might see fit to spend a bit more on it was the decision from Head Office to have a joint ‘do’ with the Braintree branch, thereby sharing the cost.

Although Terry from Packaging said it was because after last year’s bash it took three visits from Filogorm to get the filing cabinet unlocked in Crook’s office, after chewing gum had been wedged into the locks by the boys from the post room; who had been as ‘pissed as newts’ according to Ron, one of the cleaners. He had moaned about people “puking” for months and had insisted that the company allow him to order some disinfected sawdust to mop up with in case it ever happened again.

Madge had offered to put Susan up this year. Melbourne wasn’t that far but it meant a taxi as the party ended after midnight, and last year the minicab they’d ordered was half an hour late. Mr Beazley from Accounts had stood and waited with her in the reception area. They ran out of things to say after five minutes. He only wanted talk about his pigeons. They were, he said, “beautiful to watch when they were mating”.

“Make a lovely noise they do and brush their necks together”, he said rubbing the stubble on his chin. He looked the sort who needed to shave twice a day. Susan supposed he hadn’t had time to pop home before the cocktails – dry or sweet sherry or tomato juice – in the boardroom (Madge said they’d covered the mahogany table with newspaper before putting the cloth on in case of spillage). He had little tufts of wiry hair on each finger and some more growing out of his nostrils.

Half an hour seemed a very long time and after a while Mr Beazley seemed to be leaning on her with one arm arched over her head, palm flat on the wall, so that her nose was almost in his armpit. Susan still caught a whiff of stale sweat, although not so strong, when he brought the luncheon vouchers round every week. ‘Staying over’, Madge said, meant Susan could bring her things over to their flat and they could titivate together. Madge liked to use long words and was always talking about the directors convening together when she had to arrange the boardroom lunches.

There was no reason to suppose that Charles Pomfrey wouldn’t be there. After all he was management so he had a duty to put in a appearance. But Susan had woken most nights for the past month with a sick feeling in her stomach and thoughts of all kinds of imaginary situations……the Belgium office might need him suddenly on business ….his car might break down….she had even idly hung around Patricia, Mr Pomfrey’s PA, when she was putting the monthly meetings diary of ‘my Charles’ (as Patricia had called him ever since the day she joined the firm) onto her word processor screen.

Susan knew when she was doing it as Patricia would boast about any air tickets she had to book and which day ‘my Charles’ had asked her to order a bouquet for his wedding anniversary. To arrive, he had requested, at precisely 5.00pm. This, ‘my Charles’ had confided, was the exact time at which he had proposed to his wife.

Susan knew that it was a ridiculous obsession. But that made no difference. She only had to spot him through the orange tinted glass in the corridor outside her office and she felt an odd tingling sensation. It wasn’t even as if she had been in the slightest way encouraged. In fact, to the contrary. Once, down in the photocopying room she had let him go first, as it was unusual to see management in there and he looked as if he was carrying a Contract of Employment so she knew he probably wanted it in a hurry.

He hadn’t even said thank you; just sort of grunted as if in a bit of a daze and pushed past to get to the machine without even a glance in her direction. But Susan remembered the freshly-laundered smell of his shirt as he rushed from the room. If she came across it on anyone else she would stand by him or her for as long as she dared, breathing it in. By a process of elimination she thought Babysoft conditioner was a pretty close match and even switched to the brand, until her mother complained that it was thicker than most and clogged up the holes in the washing machine where the water came through.

On Friday 29th November at around the same time as Susan carefully clicked shut the freshly painted garden gate of 105 Copse Road, Charles Pomfrey switched off the engine of his Ford Cortina Mk4 and sat heavily in his seat for as long as he dared before he heard Mary-Anne’s Scholl sandals clop across the kitchen floor. It was a stupid habit of his but the effort required to bounce out of the driver’s seat the second his car came to a revving halt (he unconsciously gave it a quick toe-down in the garage) was too much.

Sometimes he felt so weary he thought it almost impossible to move his legs. Facing him, as always, through the windscreen were a row of garden tools hanging redundant on the garage wall – shears, edge clippers (at least he thought that’s what they said on the handle), a rake whose prongs always dug into his thigh as squeezed round the front of the car to get to the side-door, and a spade, its blade shiny from never having sliced through soil.

All these, and the green collapsible gardening bag, Mary-Anne had insisted they put on their wedding list. “We may only have a patio at the moment darling,” she had said leaning back upon Charles’ chest – she always sat on his lap when they had little tete-a-tetes as she liked to call them – “but we’ll need them for a bigger garden”.

It had taken a long time, their four handwritten A4 sheets of wedding list, typed at the office by Patricia, compiled in the August before last on warm evenings sitting by the side of his parents’ large pond (or lake, as Mary-Anne would describe it to her friends). A time when his squash game was really rather good and he had to miss countless matches getting ready for the wretched wedding.

In fact he hadn’t played more than a couple of games since they were married last October and had only managed those when Mary-Anne went on her first and only single trip to see her old school friend Phillipa. Charles had thought this an excellent idea and in the space of four days had succeeded in cramming in squash, a sauna with an £6.50 massage, a teensy-weensy little flirtation with the girl at Nibbles Wine Bar who wore stretch jeans that left little to the imagination, and an uproarious second stag night at Pountneys, which was, he had told himself, to make up for the first so unnecessarily terminated by the woman he had vowed the next day day to love and to cherish. He could never forgive her for turning up outside Dinners for Big Boys to drive him home.

She said she couldn’t risk her husband to be driving under the influence of drink. Would you credit it – TO DRIVE HIM HOME he would constantly remind himself, clenching his jaws together as he lay next to his wife in bed – who had yet again encouraged him to massage her shoulders before rolling over and feigning sleep. And what was so painfully annoying was that when Mary-Anne burst in, the brunette who had worn the shortest gymslip was in the middle of giving him pudding, a second helping of jelly and cream served without cutlery, spread liberally over her midriff.

Life was, Charles thought over their regular Friday night takeaway in the kitchen, with the telly still switched on in the sitting room like an extra guest and the cat jumping on his lap and shedding hairs in the chicken masala, pretty dull.

The pattern of his life which had caused this constant niggling irritation had never entered his thoughts. The only time he remembered uninterruptedly having what he termed a good time was back in the Upper Fifth at Pendlebury Hall, a minor public school recommended by Colonel Blythe, an ex-army acquaintance his father (or Captain Pomfrey as he liked to be known in the village) had quite literally worked at keeping in touch with; the part-time position of Clerk to the Parish Council was swiftly taken up by Captain Pomfrey soon after Blythe had been elected Chairman.

Charles’ career, such as it was, had never quite matched up to those hilarious schemes he and Godfrey had dreamt up to keep the Lower Third in check and ministering to the needs of a demanding Room 535. The thought of their tortuous manipulations to get the wimp Potter to clean for them by having him crawl around the carpet on hands and knees rubbing out red wine stains and having to forage for crumbs and broken crisps like a dog, still made Charles smile, sometimes at the most inopportune times like the departmental Monday morning meeting.

This little gathering of half-awake staff, shuffling restlessly on their shiny-suited buttocks, in fact began to provide Charles with a regular sanctum in which to begin to worry about the pile of mail his wife methodically placed under the brass frog paperweight the previous week.

Between Mondays and Fridays it had been one of Charles’ habits to glibly wave away letters Mary-Anne thrust before him every evening. “I am not prepared”, he said at least once a week, “to allow domestic paraphernalia to interrupt every evening”. Evenings that had, over the past few months, been much taken up with the digestion of his supper in a supine position on the sofa, belching and farting his way through the channel-hopping.

Sometimes his indigestion was so bad he thought his dinner was forcing its way back through his chest and up into his throat. On the last two weekends however, Mary-Anne had (rather immaturely he thought) taken to bouts of sobbing in the bedroom and between the sniffs had made her cause for distress blatantly clear: “If you don’t take the bloody Access bill seriously we’ll end up homeless” she screamed at him one damp miserable Sunday afternoon, before ramming a wad of torn manilla envelopes in his face.

Susan managed to catch most sight of him in the canteen. She now had a detailed timetable for her lunch hours. Monday she used for odd bits of shopping as he always went to a Planning Meeting in the basement that day, although she did sometimes try and pass through the main reception at precisely 1.12pm, when at least three times in the past her lift had arrived at the same time as his.

But Mondays weren’t really worth hanging around as he always seemed to be in the middle of the crowd, laughing or pointing at something in the paper and she only caught a glimpse of the back of his bead, where that long curly lock of hair at he nape of his neck, lay upon his collar. Fridays were a bit of a disappointment as well, as invariably he and most of the fourth floor would be in The Anchor over the road and Susan couldn’t bring herself to go back in there, not since that time last year when Madge dragged her in at Christmas, gave her a gin and orange, had six vodkas herself and then vomited all over Susan’s new dress. She had had it cleaned three times and even sprayed it with room freshener but it still smelt.

But Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays, if she made sure she went to the Main Meal Counter and not the snack bar and chose her table carefully, she could eat from a good viewpoint. He usually chose steak and chips or dish of the day, but always chips. Susan’s cottage cheese salad (she was on a diet as she had plump calves but reckoned if she was strict with herself for the next month she might dare wear 15-denier tights for the Christmas Party) didn’t take long to eat and as he always had a slice of cheesecake or roly-poly pudding she had invented ways of making her lunch last longer. She would break up her roll into small pieces and carefully spread on one or two globules of cottage cheese at a time.

During the first week in December it was confirmed that the Christmas Party was to be held in the Crown Hotel on the 23rd. Someone had drawn Christmas trees in thick felt-tip in each corner of the memorandum before photocopying – to make it look festive. Patricia had bought her dress – a red satin strapless – from Robbins & Robbins and had hung it behind her desk. She said she couldn’t take it home “cos my Mum will have a fit. I owe her two months housekeeping as it is”. She’s“laying it out” at home later…

Madge spent the mid-morning tea breaks showing off her new footwork, learned at weekly disco-dancing classes at the Town Hall. Even Ron was giving the evening some thought. Though only cocktails were being held in the firm’s building he had ordered a gallon of disinfectant and asked everyone to save their newspapers. “Trouble is”, he confided to Susan one evening when she had stayed late to finish Eric Seattle’s most prolific output for several months, “some of ‘em come back in see, when it’s all over, for a bit of ‘ow’s your father”. They’re so blotto they’ll bring it up anywhere – in the wastepaper bins, in the flowerpots, I’ve even seen it spread over the Venetian blinds”. At which point he strode purposefully out of the room wagging his head from side to side.

Susan’s night away from home had caused such a stir that she wondered what would happen if she ever wanted to go on holiday on her own. It was no use bringing up her age. The fact that she was 31 was of no consequence. Since leaving school and after that spell as an au pair, which her mother referred to as “an unfortunate interlude”, Susan’s domestic ritual had little changed.

There was always a hot meal ready at precisely 6.30pm, which all three of them ate at the kitchen table with a pot of tea and a plate of buttered Hovis. Her father would switch on the wireless for The Archers and after dinner washed up with a tea-towel over his right shoulder. “I really can’t see why you can’t come home by taxi like last year”, Dorothy Gedthorpe said from her armchair, counting the stitches on the crochet-hook and screwing up the corner of her mouth as she always did when concentrating.

Susan reckoned they had had this conversation at least half a dozen times. “Madge said she would make me very comfortable”, Susan said half-heartedly, trying to determine if her right calf was in fact bigger than her left, as she suspected. “But you’ve never been there. For all you know you’ll be sleeping on one of those camp-bed things and that’s no good if you’ve a day’s work ahead…” At which point Dorothy Gedthorpe always broke off, Susan presumed because there wasn’t really anything else she could think of as an argument against. For the past couple of weeks Susan had spent the latter part of the evenings laying out her party assessories – clutch-bag, jewellery, hair grips and making sure all was ready for packing into the pale blue weekend case with the gathered inner pockets for lipsticks, face cream and whatever else might be needed for a night away.

When the morning of the 23rd arrived her mother walked with her to the front gate and told her to wear her camisole under her dress as it “will be chilly on the way home” sand said to make sure she had a snack before the party and only drank one sherry. She said it would probably be very cheap sherry and Mrs Thorpe had to have three days off last year with a funny tummy after she’d had cheap sherry at her Christmas lunch. “Mind you”, she said, tucking in Susan’s blouse label, “Elsie Barker told me she’d had one too many”.

Madge rented her flat with two other girls who, she said, had her in stitches on Sunday mornings when they used to have brunch and talk over the night before. Although she said she was fed up with them not doing their share of the washing up. “But all in all it works alright” she said breathlessly after she and Susan had heaved themselves up four flights of stairs with Susan’s case between them banging their legs. “I dunno what you’ve got in there Suze but it weighs enough to do up an elephant” Madge said throwing herself down on the sofa (which Susan guessed would be her bed at some point that night) and kicking off her shoes.

Susan assumed Madge’s four-inch high-heels were chosen to counteract Madge’s height, which she had confided was only 4’9” in stockinged feet. Susan always felt rather gangly at 5’8” and worried secretly about falling in love with a man shorter than her (mother said she stooped and that she would become round-shouldered if she didn’t remember to keep pulling herself upright). “Best thing Suze,” Madge said unselfconsciously undoing her suspenders and pulling off her stockings to reveal legs Susan was relieved to find were as white as hers but totally hairless, smooth and shiny, “is if you get in the bathroom first and I’ll make us a toasted cheese, then you can start on your face and I’ll nip in. With any luck the other two will be late and there won’t be a fight over it”.

Susan was beginning to feel despondent. She had carefully shaved her legs last night, taking care to wash away every scrap of hair afterwards (her mother left the hair on her legs and once chastised Susan for leaving a sediment in the bottom of the bath). But she could feel some bristly patches as she undressed and realised with mounting panic that she only had the new 15-denier with her and they were as thin as anything. What if someone casually patted her kneed, she thought, like Keith Charter did last year under table at the firm’s sit-down Centenary lunch.

She could hear Madge in the kitchen humming along to ‘No-one loves you like I do’ and didn’t dare ask her if she had a razor. Anyway, she probably waxed hers Susan thought miserably. She had never dared try waxing at home as there were some awful stories flying around about how you can get stuck to the paper strips if you don’t get the timing right and Susan worried that her mother might want to come in at the stickiest of moments.

It took them about an hour. Susan was ready first. She sat waiting on the end of the sofa practising pulling her thighs together so that the foot of her dress wouldn’t rise up and cause crease lines. At ten to seven Madge was still in the mauve velour dressing gown applying her make-up, but she said getting your face right was the most important. After she’d finished putting deep brown hollows in between her eyelids and brows and painting in little flick-ups at the end of her eyeliner, she insisted Susan should have some blusher and had swept over her cheeks with a huge brush which itched.

Standing back with her head on one side to assess the result, in the way that people do in shops when they are trying to give friends an opinion without offence, Madge frowned and said Susan ought to highlight her chin as it receded a bit. Susan blushed and knew the combined effects of nervousness and Madge’s rouge would make her cheeks radiate all evening like Belisha beacons.

It was extravagant to take a taxi but Madge insisted that the evening was free after all and if you didn’t treat yourself occasionally nobody else would. Susan noticed the taxi driver looked in his mirror a great deal. Madge’s dress was so low and tight across the front that Susan wondered if something might pop out if she breathed in deeply. Madge had showed her the new bra she had sent for from Kelsey’s mail order catalogue which had boning under the cups. “Makes them much firmer” she’d said giggling and strutting round the flat with her chest shoved out front like a penguin.

Susan wished they hadn’t had the vodka and lime before they left as she felt a bit odd bouncing around in the back of the taxi but Madge had insisted it would give them a ‘lift’.

“There’s nothing worse than arriving sober,” she said liberally pouring vodka into mugs. “There’s no glasses ‘cos as usual no-one’s washed up since Wednesday and there’s no way I’m going to do it since all I’ve used are teaspoons and one cup”, Madge said pouring in the lime before handing the tearstained yellow mug to Susan, who couldn’t tell how much was vodka and how much lime cordial. She thought of her mother’s glass cabinet with the rows of brandy, wine and sherry glasses, carefully arranged according to height, that only came out for funerals and on Christmas morning when her mother asked the Pilchers in from over the road.

Charles was in the bath when he heard Mary-Anne slam the door behind her. He had had difficulty in making her understand that it was a firm’s do and other halves just weren’t invited. She would have found it boring anyway. “Do you really want to spend an evening being touched up by a bunch of dirty old men?” he’d asked when she had snivelled yet again through her face pack, “Because that’s all you’d get – straight out onto the dance floor and hands on your bum before you’d even been introduced.”

Mary-Anne had a face pack once a week. “To clean out my pores” she would whisper with her teeth clenched shut like a ventriloquist. Once when things were a bit easier between them he’d chased her round the bedroom. She had been naked except for the gunge plastered over her face and neck and they had ended up in a heap on the bed. He had to look the other way while they did it because she looked so ghastly and afterwards cursed him as there were greyish smears all over the pink pillowcases.

He had difficulty these days bending over in the water to cut his toe nails. He knew he was a bit overweight but nothing really, not compared to Derek in sales. He’d had to have a special alteration made to the seat in his car to allow it to slide back another notch so his stomach didn’t keep knocking the bottom of the steering wheel. In some ways Charles thought he would rather have stayed in with a video than go to a party. There were some good ones now in at the rental shop in the High Street and with Mary-Anne you were restricted to weepies.

Derek Elliot had seen Sex on Tap round at his cousin’s and said he could hardly control himself. Still there’d be a lot of free booze and he might get a bit of a feel with that brunette with the big tits who dishes out stationery. Charles dressed and went downstairs, switched on the TV and poured himself a large G & T. No point getting there much before 9.00pm he thought, any earlier you’d have too endure polite conversation with those plonkers from Braintree.

The queue for the buffet stretched round the ballroom and into the main foyer. Susan held a paper plate in one hand and a plastic knife and fork wrapped in a red paper serviette in the other (serviettes were only called napkins when they weren’t paper, her mother had insisted when she had once asked for a napkin at a neighbours). Her plate had become more of a soggy soup bowl, as for the past twenty minutes she and Madge had been queueing in a kaleidoscopic snake of shapes and colours, she couldn’t help clenching and unclenching her hands with the plate caught somewhere in between.

He hadn’t arrived. It made it all the more difficult not being able to explain her dismay to anyone. Her secret had been kept for so long that the mere thought of even hinting at the problem made her sweat and she could feel her dress damp under the armpits. The first hour or so, well even up to 10pm, she felt she had borne up pretty well. Eric had offered to buy her a drink three times but she hadn’t finished her tomato juice and she even had a dance with the infamous Tony Malpass, who surprisingly, once they were on the dance floor wasn’t at all cheeky and seemed almost lost for words.

They talked for a while about Ron and whether he would discard his brown overall for an hour or so, leave his guard room at the office and come and join in. But then the music slowed and Malpass sort of pulled her closer and allowed one arm to slide slowly down past her waist, as far as her thigh. Susan couldn’t bear the taught of him feeling her suspender through her dress, but then thankfully the band stopped and announced an interval.

Susan didn’t cry at the funeral. Madge did, which Susan found rather odd as she didn’t think Madge had hardly ever spoken to him. The announcement was the worst shock. The band leader came up to the microphone just as they were finished pudding, profiteroles with fresh cream. He coughed nervously but nobody took any notice, so he coughed again and tried to clear his throat to gain attention. On reflection Susan realised it must have been very difficult to know how to start. “Ladies and gentlemen… I’m afraid there’s some very sad news…” Susan kind of guessed then. I mean it had to be him. That’s what life is like, she thought, hitting you when you’re down.

Laying in bed, the following Tuesday, the flannelette sheets drawn up under her chin in a soothing ruffle, Susan kept going over the bandleader’s words in her mind. ‘Heart attack’ and ‘lost control of his vehicle’. She knew she couldn’t stay in her bed forever staring at the roses climbing up the wall until the bit where a damp patch on the wallpaper from the broken gutter had caused the trellis to mangle into a brown mess. Her mother had telephoned the office and said something to Madge about it being the ‘time of the month’ and could Madge say Susan had a nasty cold.

Susan left her bed on Thursday, had a bath and dressed for work. Her mother of course had no conception of the real problem and Susan could no longer bear to be told to pull herself together. On the kitchen table propped up against her boiled egg with its knitted cosy, was a letter curiously addressed to Miss S. J. Gedthorpe. Susan hardly ever received mail. Very occasionally a circular about stretch covers or loft insulation, but never any with S J; she only used her second initial when filling in forms.

She didn’t open it but put it in her bag. Susan suddenly fed very claustrophobic in the tiny kitchen; her father was stoking the Rayburn in his tartan slippers that were so worn and misshapen he walked on the sides and her mother was tidying her cacti, picking off the dead spines and placing them carefully on a piece of kitchen towel.

She opened the white envelope on the bus, just past the level crossing. Dear Miss Gedthorpe, you have won a dream holiday for two…Susan smiled. Babysoft wishes to thank you for entering… She had only decided to go in for the competition when she had bought a pack of four bottles of the stuff on offer and had found she enough coupons straight away.

By the time she was in the office lift, her carrier bag firmly wedged between her legs, Susan had begun her check-list for travel – aspirin, travel iron, clothes pegs (in case she needed to hang anything up on a balcony) and a pack of razors, she was taking no chances this time. She hoped Madge would wear a swimsuit instead of the topless leopard-skin bikini she had shown-off last summer. She knew Madge would go with her – anything for a laugh, as Madge would say.

Flattening herself against the lift wall as Beazley manoeuvred his bulk to make room for the post trolley, Susan remembered the day Madge strutted up and down in the Ladies half-dressed with suspender belt and stockings still on and a fake fur ear-muff clenched between her buttocks. Still, she felt safe with Madge – she knew she could deal with men just by opening her mouth and hurling out some shop verbal weaponry. It might be fun she thought, they could have those brunch sessions Madge always talked about and chew over the night before.

When she felt the familiar jolt as they reached the sixth floor, she bent over and gathered up her things. “Excuse me”, she said, edging past Beazley with her brolly tucked under arm, the spike dragging across his paunch. “Hey, watch it”, he hissed, his loose mouth showering her right ear with spit. He shifted slightly and Susan was momentarily pinned between his stomach and the trolley. She flinched but only briefly, before pushing past and marching off smiling towards Madge’s office. They had a lot to talk about.

Penelope Lewis