Fiction Short Story

The Present

If she just had her family back, Nia thought. Together they could chart a way out of the breaking.

Chilling the wine might have been a mistake, Nia acknowledged, after she downed her second glass in as many minutes. She watched a woman and a girl kicking a ball back and forth, hard, on a clear patch of clover. She couldn’t imagine wanting to move. The September evening seethed brutally hot and humid, as if a hard rain, instead of falling, had melted into the air.

Her mother’s train arrived in an hour; she’d meet them at the after-concert reception, a surprise for everyone but Nia. A rare visit from Connie. In the years since Nia’s father’s death, the surviving family members had fanned out like spokes on a wheel, whirring around an empty center. They hadn’t shared a meal together in twenty years, Nia and Connie shuttling between Nat’s house and Margaret’s for holidays, until Connie moved to Atlanta.

Tonight, Nia would stop the wheel and bend the spokes until they touched, fold them inward to make a new center.

Gabriel refilled her glass with tepid water. She wrinkled her nose and he laughed, leaning over to peck her cheek, the movement pressing his shirt to his chest until it was speckled with sweat. Honest sweat. She wished that she’d been the one to haul their picnic things up the slope, instead of delivering Theodora and Claude to the rehearsal space. The twins were simultaneously fighting and begging her to let them skip the reception so they could go to a better party closer to home. Nia lost her temper, lectured them on perspective, and confiscated their phones, which might as well have been their lungs for the choked objections they gave her. Gabriel—easygoing, funny Gabriel—would have made the same point without receiving the particular surly look of loathing their remarkable darlings reserved for her.

She hid her frown by taking another sip of water. She knew the pendulum of their children’s affection would swing toward her again, but it seemed a long way off. The lukewarm water made her thirst worse, and now her cheeks tingled from the wine. She had the distinct sensation that her makeup was sliding off her face, from the wine or the heat or nerves. Margaret was late. But she’d accounted for that contingency when choreographing this unannounced family reunion.

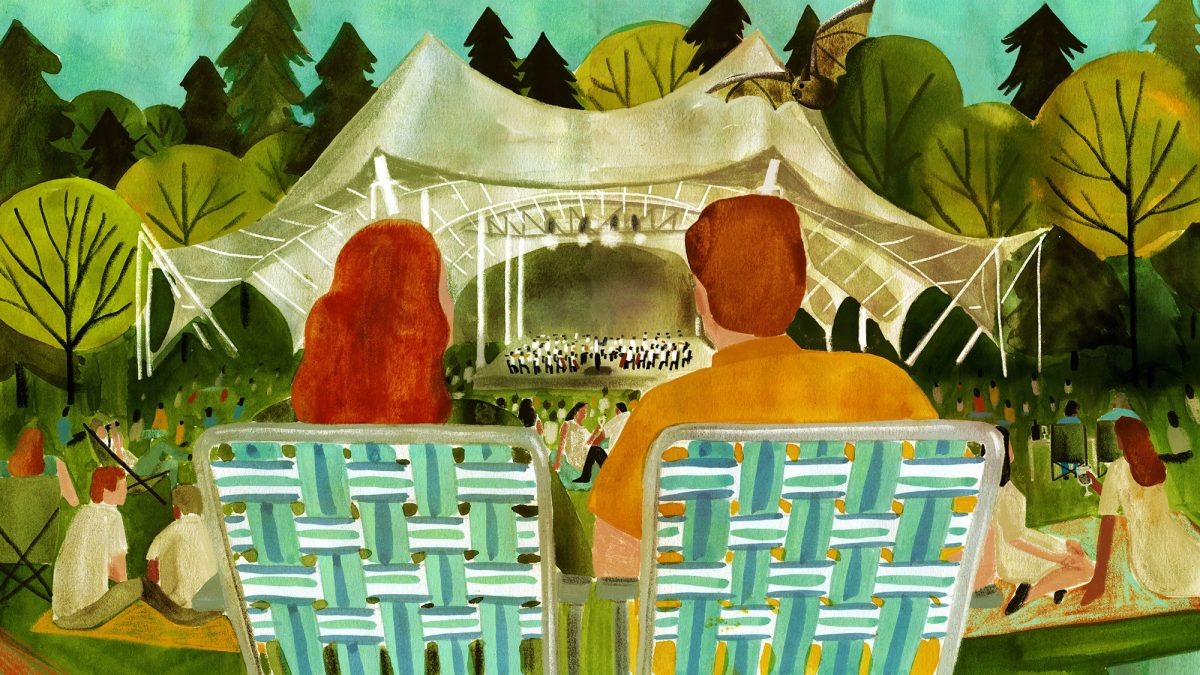

The pavilion loomed in front of them like a hollow mountain whose edges had been buffed smooth. When she was a child, she and Margaret and Nat, who were in college by then, came here every summer with their parents. After the macaroni salad and sandwiches and loose-skinned clementines, after the sun dipped low enough that her siblings crowded the citronella candle to read their programs, she used to close her eyes and wait for that peculiar near-silence, the crowd’s whispers little more than breath against skin, everyone placing their limbs precisely to avoid making a sound. Like a temporary kinship with her, so many people trying not to call attention to themselves. Often, drawn into the phenomenon, she forgot to listen to the music.

There were exceptions: one night when she was twelve and her siblings were both home for a visit. Margaret had landed her first big client, so their parents had packed a bottle of champagne in the cooler. She remembered her father fiddling with the cork and her mother, grinning, pointing the bottle away from the yellow candle in its tin pail. Someone poured Nia a splash in a plastic cup. She nursed it, taking tiny sips of the golden taste.

In thirty years, things had changed. Not just between her siblings. Everything. Margaret had her eyes closed, lying back on the itchy green blanket, the tarp beneath crackling faintly as she shifted. Nat was staring at the stars. Her parents were leaning into each other, focused on the orchestra. Nia felt alone but connected to them all as she soaked in the deliberate hush of the lawn. She didn’t expect much from a piece of music with such a stodgy name—“Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis”—but the first notes gripped her attention. They sounded like an ending, like the gate closing on a twilight convent. And then she was inside everything she wanted to love and everything she couldn’t.

Margaret and Nat saw, understood—what? Something. Stealthily they refilled her plastic cup with their champagne but said nothing, their discretion the greater gift. She drank to stop herself from weeping, and she never listened to the piece again in public.

In thirty years, things had changed. Not just between her siblings. Everything. The trees—artificial, with speakers piping native birdsong—were massive, the pavilion renovated, the bugs too few to bother with citronella, and—since nobody traveled anymore but money must be spent—the concertgoers had taken picnicking to extremes. She couldn’t count the number of wooden tables unfolded to knee height to accommodate low-slung padded chairs. Vintage lanterns, cocktails in cut-glass pitchers, linen napkins—all standard now. After she ran into two partners and an associate in one evening (Dvorâk; thankfully the kids were with a sitter and she’d dressed up), Nia too bought a picnic table, chairs, and a china set just for these evenings. Gabriel rolled his eyes and insisted on using their old containers for their usual dinner: farro salad with lemon and olives and artichokes, skewered melon and berries. No garlic, nothing leafy that could stick in her teeth. She was a partner, but that didn’t mean she could afford to let appearances slip.

“Uncle Gabriel! Aunt Nia! Look what I got!” Nia’s head nearly detached from her body at the force of Bernardo’s embrace.

“I think Bear’s grown another three inches,” Gabriel said, getting up to hug Camila and Margaret.

Nia thought she might topple over if she stood. “Tiny binoculars?” she asked her nephew.

Bear shook his head. “It’s a microscope. With a light so you can examine things.” Gabriel grinned—he should have been a science teacher—and pointed out an anthill at the edge of the blanket. Bear scampered over.

“Binoculars would have been a good idea, actually, to keep him occupied. Next time.” Margaret pressed a quick kiss to Nia’s forehead and sat down heavily beside her. It was still light enough to make out her sister’s strong features, the wisps of red hair shot with white that patched her skull.

“Too hot for a wig?” she asked. Margaret nodded.

“Speaking of hot, Margaret baked,” said Camila, unpacking their cooler.

“I did not bake. There was no heat involved.”

“You actually measured ingredients, so I think it counts. Anyway, we should eat them first. They’re going to melt.”

“You made peanut butter creams?” Nia’s voice climbed a giddy octave. Another sign she’d had too much wine.

Margaret pulled an old lunch bag closer, its surface dripping condensation. “Just a half batch,” she said, trying not to seem too pleased by Nia’s enthusiasm. The pale, chocolate chip–studded square she offered Nia was already dissolving into the wax paper. Icy, sweet, buttery, salty—it was heaven. Nat used to love telling how, in elementary school, long before Nia was born, Margaret had marched up to the kitchen door during lunchtime and requested the recipe from Mrs. Abruzziano, the woman who ran the cafeteria. An archivist from the start, Margaret was.

“Get one before they eat them all,” Camila warned Gabriel. He was hunched over, eyes rolled heavenward as Bear, ants forgotten, moved the microscope over his uncle’s scalp.

“Your skin is disgusting,” the boy said happily.

“Thanks,” said Gabriel, wincing. Nia grinned. Claude and Theodora had been the same way when they were six.

The peanut butter creams disappeared in minutes. From bowls wrapped in kitchen towels, like swaddled infants, Margaret dished out tabbouleh, tortillas, cucumbers and raw zucchini with chile and lime, tofu in a dark sauce redolent of garlic and soy. Nothing went with anything else and everything was delectable.

“Aren’t you too hot?” Margaret asked her, waving a fork in Nia’s general direction, twirling it to emphasize her dress, her jacket, the long silk scarf that camouflaged her midsection.

“Yes,” said Nia. Margaret worked for herself, often for clients who never saw her face or heard her voice, just sent their money and received their histories. She dressed with a bohemian flair that was probably Camila’s doing, but she had no colleagues. Nobody cared in the slightest what her sister wore, and to Nia’s annoyance Margaret took the luxury of comfort for granted.

“I don’t know why you let them bully you into this facade—” Margaret began.

“Nia, are the kids too old for water balloons?” Camila interrupted. “Looks like it’ll be hot tomorrow. We’ve been saving our water allowance for Connie’s visit.”

“They’d love it. Let’s hope for no health crises this week.” Last year, their mother’s trip had been derailed by an outbreak of antibiotic-resistant cholera in Iowa.

Nia turned to put away the untouched farro salad and pull out the fruit, just in time to realize that a ball was careening toward them. The calculation happened instantly: If she ducked, the ball would hit Margaret, so she turned just enough to take the impact on her temple instead of her nose. She heard the ball ricochet off the cooler before she felt the sting. One hiss of pain and Gabriel was beside her, gently peeling her hand away from her eye. She’d lost her contact.

“How hard did it hit you?” he said, examining her head.

“Hard enough to jump-start my hangover.”

“What’s a hangover?” asked Bear.

Nobody answered him as the little girl and her mother Nia had noticed earlier ran up, apologizing profusely. Nia waved them off, leaving the conscience-soothing to the other adults. She rummaged in her purse to find her backup glasses. The prescription was a few years out of date. She should have listened to Gabriel—blurry Gabriel, now—when he told her to get the implants. She’d missed an opportunity to plan ahead, and now she wouldn’t be able to see what was coming next.

*

They all preferred sitting on the lawn during concerts, but this time Nia bought mid-pavilion seats, so the kids could see them from the stage. And she wanted to spot Nat and Malin in the crowd.

The chimes rang and the lights flashed just as they settled. Most of the musicians were tuning their instruments and chatting, but a few were still ambling onto the stage, which always struck Nia as a bit unfair, since singers were expected to file onto the risers silently and in an orderly fashion. Probably a safety and liability issue, her lawyer’s training told her. Still. The slight injustice rankled.

Her head throbbing from the wine and the minor injury and the old prescription, she swiped through the program on her phone. It was plastered with the name of her firm, a major donor to the youth orchestra, which had expanded rapidly over the last few years. Parents wanted their children to appear well-rounded for college applications, of course, and besides, who could predict what skills would matter next year, or five years from now, or in a generation—whenever the exodus came? Rumors of a lottery or a tiered ranking system persisted. Thanks to Nat, Nia knew better than most that they were unfounded. The prototype ships kept blowing up.

Gabriel nudged her and she looked up to find Claude—she could tell by his red hair—standing on the topmost riser in the baritone section, his attention caught by one of the taller tenors. She watched as the other risers filled, trying to make out Theodora among the altos. Nia wished she’d go back to dyeing her hair green.

She had no hope of spotting tiny Andromeda, Nat and Malin’s daughter, who was somewhere in the middle of the cellos.

“There she is. Second row, fourth from the left,” Gabriel said, thinking she was searching for Theodora. His mouth hovered next to her ear just a touch longer than necessary.

They’d met when she was a fourth-year associate putting in pro bono hours at the family court where he worked. When the power went out, unscheduled, he offered her his cup of coffee, still hot, and a date the next week. Quaint, almost. She was reeling from her father’s death, Nat and Camila’s divorce, Camila and Margaret’s marriage, her mother’s move to Atlanta, the strain of watching the world disintegrate. Not to mention nearly a decade without proper sleep. She pushed Gabriel away for all the usual reasons, but the man just stuck, briar-stubborn. He was beautiful, which didn’t hurt, worn rough and tender from years of sad stories and long nights. They went to bed together soon, then often, and when she suggested they elope to Rio she told him it was because she wanted to love him in as many cities as she could before they sank. Which was true.

She didn’t tell him that Nat wouldn’t sit in a room with Margaret long enough to witness his other sister’s happiness, though this was true too.

In twenty years Gabriel had never made her feel unlovely. She adored him utterly, recklessly, pushed aside all her fears to make a family with him. She would tell him again how much she loved him, would admit her plans—but a familiar, unctuous voice addressed her, faintly but unmistakably emphasizing the “Ms.” before her name.

Like an unhurried crane, Philip Dillard folded himself into the seat next to her, his bony knees grazing the back of the seat ahead. Despite the humidity, his cream linen suit was crisp. Nia imagined swabbing her face against his starched lapel, leaving it smeared with sweat and makeup. Immensely satisfying.

“Philip,” she said, ignoring his formality. “What a lovely surprise. Do you have grandchildren in the orchestra?”

He blinked, not expecting the hit. “My daughter,” he said. “First clarinet.” He pointed toward the center of the stage. Nia squinted, thought she could make out a reedy blonde girl in that direction.

“You must be so proud,” she said.

“Indeed. We didn’t have a chance to finish our discussion about my offer—”

Just then the concertmaster stood and played her A, and the audience fluttered and subsided into one giant organism of attention. A bird flickered in the pavilion rafters, tipped gold in the waning light.

Nia took Gabriel’s hand, grateful for this short respite. Thank goodness the program was short enough to dispense with an intermission. She had one Sibelius tone poem and all of Beethoven’s Ninth to find a diplomatic way to tell Philip Dillard to go fuck himself. As if she’d ever report to the man who’d outed her to solve a PR problem.

Her glasses slipped down her nose, slick with sweat, and she pushed them into place as the conductor walked onstage to polite, curious applause. She wasn’t the first AI conductor in the country, but she was the first in Cleveland—hence the crowd, unusually large for a youth symphony performance. The conductor had named herself Georgiana Szell, after the Cleveland maestro she most admired; in September she’d take up a post as an associate conductor with the orchestra. It was unusual for an AI to elect human embodiment these days, when humans were caught at some unknown edge, ants traversing the lip of a shattering glass. Nia thought she might understand the conductor’s choice, that maybe she felt some hunger to coax perfection out of endless possible disasters with a mere flick of her baton.

But once the music started, she forgot both Georgiana Szell and Philip. She was riveted to Bernardo, who tipped forward, sitting on his hands to see between the shoulders ahead of them. Her gaze roamed with his, over the orchestra and the choir, lingering on the cellos, the huge double basses, the timpani in the back, instruments bigger than he was. She felt a fierce need to protect him, to surround him like an electromagnetic field, invisible, rippling its power every time he moved. Nia knew even better than her sister, the narrative genealogist, that family is a set of stories we tell ourselves. She wanted a whole anthology for Bear, Andromeda, her children. For herself too.

Nia knew even better than her sister, the narrative genealogist, that family is a set of stories we tell ourselves. The Sibelius piece ended to hearty applause, which continued as the soloists for the Ninth walked onstage and took their seats, the tenor and bass in white jackets, the mezzo in sparkling gray, the soprano in red, of course. Nia sank further into her seat, careful not to touch Philip’s arm, which had casually claimed the armrest between them. She balanced her bag on her knees, where the weight would tether her. She was ready, focused. She wouldn’t be overcome by the Ninth.

Soft suggestion to brash pronouncement, the music began. As unobtrusively as possible, Nia scanned the crowd in front of them. Nat liked to sit close, to be enveloped by the experience. In the middle of the first movement, three rows ahead to her right, she was sure of it: her brother’s golden hair and Malin’s buzz cut. She allowed her fists to uncurl, flexing her long fingers.

After the last ovation, she’d dismiss Philip by explaining her mother was waiting. She’d offer to take Bear to the reception so that Camila and Margaret could take their time walking to the restroom; Camila would say yes on behalf of Margaret’s knees. Gabriel would gather their things. By the time Nat and Malin reached the reception, Nia, Bear, Gabriel, and Connie would be waiting, and then the older kids and Margaret and Camila would arrive.

Some outcomes were easy to predict: Bear and Andromeda would delight each other; Claude and Theodora would be polite, counting the minutes until she returned their phones; Gabriel would give her an exasperated look but avoid confrontation until later; Malin would discreetly assess Camila; Camila would be mortified, for which Nia was truly sorry; Connie would be desperate to get all four grandchildren in one picture. But Nat and Margaret’s reactions—those she couldn’t foresee. Despite her preparations—the public place, the children, their mother’s visit—their hurts were deep canyons, where disaster lurked.

New, cold sweat glazed her skin, and she was thirsty, so thirsty. Surely everyone could tell how exposed she was—

Like that night on the lawn, the fantasia and the champagne. And then the night she’d called her mother from the law school library, distraught because for the first time she didn’t feel like the brightest student in class, facts crowding her mind, ready to be summoned at her whim. She knew this was a necessary humbling, but her belly was still acid with anxiety and too much coffee. She was caught in the present, her mother said, like a broken branch lodged in the riverbed, buffeted by the eddying current. No memory of the forces that propelled it to this place, no awareness that given a little time, a little rain, it would float on. Take the long view , Connie said. But first take a shower .

For years now, the long view had been misted over, a windshield that wouldn’t clear. No way to navigate, and the present just as murky. If she just had her family back, Nia thought: her sister who raised the dead from history, her brother who talked to starfaring ships, her mother who’d taught them all how to mourn. Together they could chart a way out of the breaking.

There was a brief lull, a held breath between the third and fourth movements, and at that moment, in the rustle of stretching legs and muffled coughs, the bird that had been swooping through the rafters plummeted into the crowd. Except it wasn’t a bird.

The bat landed on Philip Dillard’s shoulder. Swiping wildly, he flung it toward Nia. It slapped hard against her bag and fell into her lap. Someone behind them heard the noise as a clap, and then came a weak swell of applause, strangled as people new to the symphony were hushed by their more experienced neighbors. Philip had frozen in chagrin, but as the clapping crested he unfolded his limbs and dashed from the pavilion, like a communicant who scuttles out before the closing hymn as the pious frown with disapproval.

(At the mistimed applause, Georgiana Szell’s head swiveled, just a few degrees more than a head ought to swivel, just a bit too fast. No one noticed, except a competent but undistinguished cello player named Andromeda, who nearly missed a page turn.)

In the agonizing moments that followed the bat’s fall, as the orchestra modulated into the ominous tones that would be reshaped by the fourth movement’s prime melody, Nia felt time slow. She shed a skin of pain and heat. The sound in the pavilion rebounded off every object—the enthralled audience, Bear’s forgotten microscope, the particles of rosin dust carried aloft by gentle currents—and came back to rest in her mind. Her vision burst into bloom.

Three rows ahead, Nat would turn, looking for the source of the earlier gasps, his gaze finding Camila as she absentmindedly lifted Margaret’s hand, joined with her own, and grazed it with a kiss. Nia could see it: how she’d set the wheel to spinning again, how this night would turn them all back into spokes, rays impossible to divert from their separate paths.

Then the image blurred and her head echoed with dull, damp pain. With a start she remembered the bat. She had already steeled herself to kill the bat before it had the chance to bite, but it hadn’t moved. It was nestled against her thigh, one diaphanous wing extended, and the head—frightening although she did not wish to be frightened—angled as if it wanted to sip the dim light, or the perfect notes from the air, here in the exquisite present.