Fiction Short Story

A Precious Stone

“A humble name. Shi Tou cannot be mistaken for a precious stone. To be something ordinary makes you less fragile.”

Mama used to keep a stack of receipts clamped together by a binder clip in her purse. She took them out at night and cross-referenced them with her bank statements, line by line, her pen making small dots in the margins. As a child, Boris peeked through the keyhole of his father’s study to watch her pen characters onto thin rice paper sheets. In English or Chinese, her cursive carried a scholarly slant, and she wrote in angular curlicues that held a commanding shape on the page: f ’s and h ’s and k ’s. On occasion, Boris would accompany Mama to the bank, where they’d idle in the parking lot in their hunter-green Toyota Corolla, Mama filling out forms on her steering wheel, Boris relishing the summer feeling of snuggling against the velour seats, the two of them soaking in the trapped heat while the car billowed warm air in loops.

These days, her financial planner collected dust. Her sharp wit now dissipated into the air when she spoke. Weightless and airborne. He found himself nodding along to Mama’s mantras even as they no longer applied to his adult life, which had taken its own shape, one she could never understand.

Boris didn’t mention these thoughts when he visited Mama at the assisted living center in Gaithersburg, which was down the street from the materials research center where Boris worked. On weekends, he brought groceries from the Asian supermarket and letters from the mailroom downstairs. They’d sip on chrysanthemum tea and snack on frozen dim sum while Mama—winded, though mostly lucid—shared stories from her days as a young beauty.

Today, Boris brought over grocery bags containing ginger, a knobbly head of cauliflower, and a tin of sliced braised beef shank. “Ma,” he said, as he hobbled into her studio apartment with plastic bags hanging full by his ankles. “You need to remember to lock your door.” His phone chimed with a text from his boyfriend, but he ignored it as he puttered around the apartment. His two worlds were better off separate.

He removed his sneakers at the door and pinched them together, making a neat pair, then slid into his set of blue-and-white house slippers and started unloading the groceries, the plastic undersides of his slippers click-clacking on the kitchen’s linoleum tile.

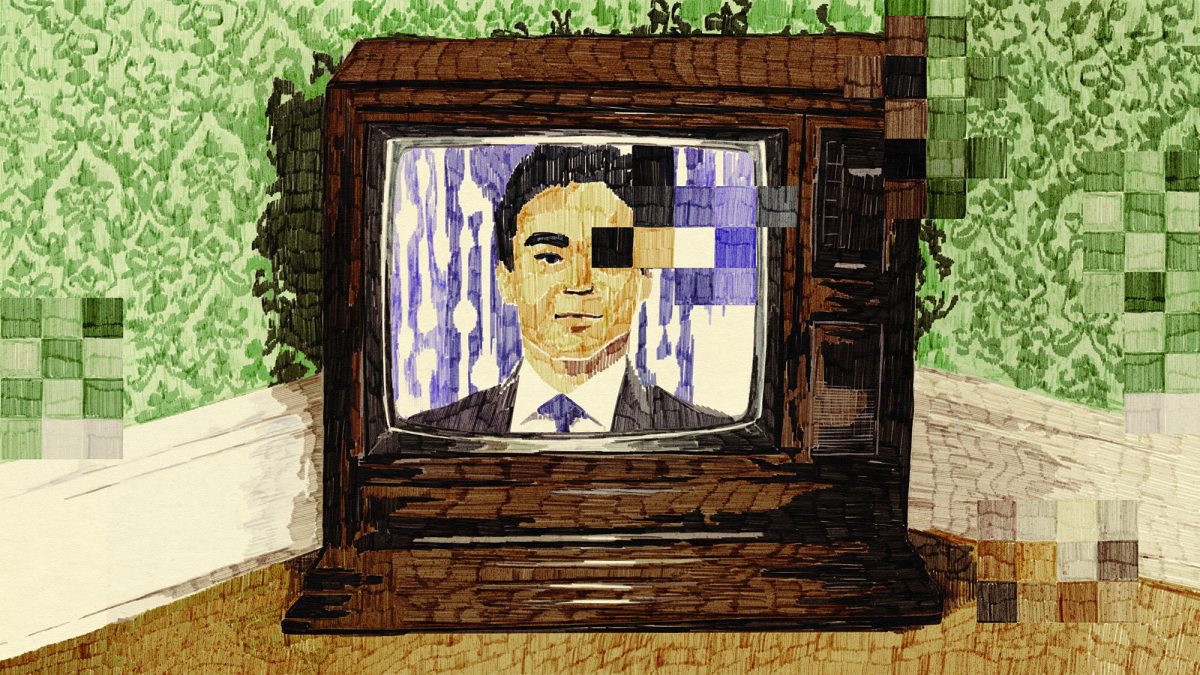

“Shi Tou,” Mama said from the recesses of her crowded living room. She’d used his Chinese nickname. “Your father was on the TV today.” She pointed her remote in the direction of her beloved cathode-ray tube television set, which occupied an entire corner of the room, wedged between the window and her faux wood desk, where her computer screen projected an ever-running stock chart in phosphorescent green electrons.

“No, Mama. He’s in Singapore now. He won’t be on your channels.” Holding a bowl of sliced Asian pears, he kissed his mom on the cheek. A light peck. Her skin felt papery, delicate on his lips.

“Shi Tou, I saw him. He’s the host on Zhong Qiu Wan Hui .” Her voice was insistent, tapering into a whisper. Boris looked at Mama on her corduroy couch, at the sunspots on her face and her black eyes, which peered into his with curiosity.

“Okay, Ma. I’ll take a look.” He took the remote from his mom and flipped through the Chinese programming to the CCTV-1 channel, which was broadcasting reruns of the festivities. His heart pulsed in his chest as his father’s sanguine face gazed back at him for the first time in twelve years.

A distant memory resurfaced: his father, herding him through lines of taxis at the airport with his hand flat against Boris’s back, muttering, “Ni bu gai lai.” You shouldn’t have come. Over and over, like a spell. The last time Boris had seen his father was when Boris had searched for him in Singapore.

“See?” Mama bit down into the gritty white flesh of the pear slice and munched on its ochre skin. The fruit crunched loudly, without pause. They both looked at the TV.

His father wore a childish grin as he hopped around silk-robed folk dancers with coiffed hair. He was balding at his temples but had the spirit of a younger man. With a flourish of his hand, Boris’s father ushered a ballad singer and her guzheng accompanists to the stage. His forehead—powdered and unlined—betrayed no signs of a complex inner life, as if he’d stopped aging after returning to the mainland.

On the TV, his voice boomed as he announced the next variety act in his dramatic, native Beijing accent. The plosives and fricatives from his lips sizzled in the program audio. Boris remembered this voice, the way it had announced his father’s arrival as he rolled his suitcase over the threshold of their old house, told grandiose stories about China, and grew guttural after he’d consumed too much alcohol. This voice, Boris recalled, had powerful ways of both livening and suffocating a family dinner. Sometimes the hush that descended after his father left for his next flight felt more comforting than the brief merrymaking that occurred during his visit.

Boris still heard the voice in his dreams, and now it reached him over airwaves as if distance were no barrier. As far as he knew, his father still wired money to his mom’s account—ever the dutiful provider.

The camera panned over to the next act, moving across the man’s face and rendering it into laggy pixels. He used to worship this man. Boris felt he was looking at a stranger.

The television screen fizzled and spewed static snow. The noise crackled in the confines of the small apartment.

“Shit!” He shot up and squeezed the volume button down until the TV went mute. “Sorry, Ma.” He looked sideways at his mother, who wagged a playful finger at him.

“I know you started cursing in middle school.”

“I never cussed in front of you, Ma. You’re too scary.”

“What’s cuss? You mean curse?”

Boris chuckled as he dug behind the television set for the streaming box. He unplugged and plugged the cables back in, and the Chinese television program flickered back to life. The ballad act had been succeeded by a Cantonese pop ensemble whose fifty-some backup dancers waved their long sleeves in perfect synchrony. Boris took a step back to look at the TV screen. The bouncing pixels painted colors across his vision and played back fuzzy nonsense.

“Good thing I know how to help you with your complicated setup here, Ma.”

“Good thing my son went to school for engineering.”

Boris thought back to the night before his graduation, when Mama had told him his father wouldn’t be able to attend due to a missed connecting flight. He knew she was disappointed, but her expression was subdued, her eyes soft as they searched his. He kept a straight face and shrugged. “No matter,” he’d said, putting his arm around her. It was their unspoken agreement to walk around his father’s absence without acknowledging the hole it left, an inky gaping maw.

“Come watch TV with me,” she said, patting the sofa cushion next to her.

Boris pretended not to have heard and started fiddling with the TV cables, organizing them into neat rows.

“Ai ya. Kuai lai, kuai lai. You’re going to miss the lion dancing.”

“One sec.” Boris went into the kitchen, remembering the treat he brought for his mom. He picked up the rope handles of a red-and-gold gift bag and removed a metallic tin that he placed on the coffee table. Four mooncakes, stamped with the character for good fortune, sat snugly within. Round and yellow like the harvest moon. He cut a mooncake into four quadrants, ensuring that each section had a piece of salty egg yolk, then offered a slice to his mom.

“Cheers, Ma.”

As they ate the rest of the mooncake in silence, watching the lion dance, Boris felt time slip. The feeling was niggling, like he had forgotten to do something. Yet it was already happening: his mother dying, his father reappearing, time prevailing and progressing in the ways that his family could not. Their shared moment was already deflating.

Boris closed his eyes, wishing silently to unknown celestial beings for this moment to be preserved in memory. In entirety, he hoped, not in bits and chunks, for pieces always tended to slip away the easiest.

Mama yawned next to him and then closed her jaw with a snap. She gave Boris a warning look, knowing what he would say next.

“Well,” Boris said, “I guess it’s time for good night.” He cleared plates away as his mother glared at his profile.

“My son—my grocer and my security guard.”

“Your best friend too.”

“You wish.”

“I do wish.”

Mama grumbled and stood up. “Your earnestness is too much. Girls are going to think you’re soft.” She limped to her bathroom and shut the door. Boris turned off the television, and its unbroken static hum dropped to nothing. It was quiet in the apartment complex. Boris checked his phone as he waited for his mom to finish getting ready for bed. Three notifications blinked at him. Texts from Matthew.

Boris heard Mama click off the light switch as she walked over to her twin-size bed in the corner of the room. She wiggled into her covers, and Boris tucked her plaid coverlet up to her chin. She was shivering a little and so thin.

“Shi Tou. You need to spend time with your friends. Don’t worry so much about me.”

A familiar warmth spread from his chest to his throat. He felt transparent under her gaze. “Shi Tou is a funny name. Rock.”

“A humble name. Shi Tou cannot be mistaken for a precious stone. To be something ordinary makes you less fragile.”

Boris considered his mom in the lamplight and saw how the light of the moon carved along her chin, illuminating the glimmering particles in her skin. Boris felt her eyes on his face too. There was still so much he needed to discuss with her. About Matthew. About his father’s mistress and second family. He felt the expanse of space between him and his mother, pregnant and impregnable. Together, with his father, they formed a triangle of buried secrets, things they were all unwilling to say.

“Oh, the moon,” Boris said. “We forgot to go outside.”

It was customary for them to admire the harvest moon together—Boris and his mother. As a child, Boris had felt silly traipsing out to their backyard on the fifteenth night of the eighth lunar month, hand in hand, each year until she had to sell their house. As an adult, he could no longer take a moment like this for granted. He peeked through the blinds of his mother’s window.

“Look, Mama. It’s huge tonight.” But Mama was already asleep. Wispy hair framed her resting face. Her mouth, agape, blew shallow breaths into the space between them. He clicked off her bedside lamp. The moon glowed through slits in the window blinds, and he hoped that he was doing a good job of loving her.

The moon glowed through slits in the window blinds, and he hoped that he was doing a good job of loving her. *

Outside, Boris waited for the bus. He clicked open his lighter and extracted the long finger of a cigarette from its case—his father’s old case, another remnant of his foregone life that he hadn’t come back to reclaim. Boris took a drag and expelled a cloud from between his chapped lips.

Mama seemed thinner today, he thought. Her mass, like her words, diminished every moment, and Boris wondered where the lost weight had gone. Did it convert into dust and energy, like a sandy and molecular exchange between the realms of consciousness? Or was it wholly unaccounted for, spent and gone? Thoughts of mortality had crept into his daily work over the past week. As he scanned polymer samples and waited in the frigid reflectometry lab for the results, he wondered why he had chosen to study inorganic matter when his most important questions revolved around the living.

Checking his watch, he took one final drag of his cigarette and ground it into the pavement with his toe. The ten o’clock bus was almost here. Boris unlocked his phone screen and replied to his waiting texts as he shivered.

Sorry , he texted his boyfriend. I’m waiting for the bus.

You could’ve told me you were working late , Matthew texted back immediately.

Yeah oops , Boris responded, then paused, feeling suddenly criminal. Boris had still not brought Matthew to meet his mom. His lie felt magnified in the silence after his text, and Boris struggled to find the words that would make this right.

Another text appeared from Matthew: Hope you’re not burning yourself out.

OK. Thanks.

A few seconds passed, and then Matthew texted again. Actually, I think I’ll sleep at the hotel tonight for my interview. The recruiter booked me a room.

OK , Boris typed back.

I’m not doing this to punish you. I just really need the space.

OK.

Can you say something other than fucking ok!!

Boris wanted to tell Matthew everything. His fingers hovered over his touch keyboard. The bus was pulling up to his stop. He wiggled his thumbs experimentally.

I want you to stay.

Not waiting for an answer, he hoisted himself up the bus steps and into the belly of the car—not too close to the driver as to be one of those doe-eyed do-gooders hogging the wheelchair-access seats, nor too far in the back to be screwed over by an immovable blockade of human bodies. But this bus hardly ever got passengers after eight. In fact, there were only three other passengers. A woman sitting in the front, clutching her purse to her body as she hung on to a metal pole, and two boys way in the back, giggling and making out the way Matthew wished he and Boris could.

Matthew. He had met him as a friend of a friend, and after a few dates, Matthew had asked Boris to meet him for lunch at the Washington Ballet, where he was a dancer in the corps. Boris waited by the stage door, holding a paper bag with paninis to share. Matthew was ten minutes late when he leapt and spun through the door, showing off for Boris and kissing him full on the mouth for the first time in public. Matthew ushered him inside to say hello to his ensemble of friends, but Boris was still reeling from the kiss. Matthew was nothing like his first, who had demanded a secret relationship, a love that came alive in the shadows.

The bus squealed to a stop, snapping Boris out of his memories. A teenage girl wearing a torn-up backpack entered and sat across from the woman in the front. Metallica leaked from her headphones as she chewed her gum and popped pink bubbles. The standing woman clutched her purse tighter and strode toward the middle of the bus. Surprisingly, she decided on the seat beside Boris’s, and the air shifted, blowing her perfume scent into his face so he smelled it in his next breath. She began to speak to him with too much familiarity, as if they were one another’s confidants.

“I thought we were in a good part of town, but I severely misjudged,” she said, glancing at him with taut lips. “You seem like a dear, so I hope you won’t mind an old lady seeking out your company.” She looked older than his mother, though how much older Boris couldn’t tell. She reached into her designer handbag and pulled out a half-pint water bottle and took a miniscule sip before re-capping and sliding it back into her purse. Boris was captivated by her hands, which were covered in bulging veins that snaked up her wrist.

“Today’s youth in particular,” she continued, “have no sense of decency or how to be considerate.” She enunciated the ending consonants of her words, the th of youth and the te of considerate . He thought about his mother’s hands, which were unadorned and unpolished but always moving—cutting vegetables, cupping dirt from her potted plants, cradling dough in her palm while she pinched pleats with her fingertips. She still wore her gold wedding band. If Mama were here, she would keep to her corner of the bus, eyes averted and face forward. She avoided conflict even when conflict came to find her. In the store, when strangers told her to go back to where she was from. At dinner parties, when her friends asked when her husband would be home. Each time, Mama deflected to hide her true feelings, but he saw how she spun her wedding band when her fingers jerked, a nervous tic.

“And those two—” The woman leaned confidentially in Boris’s direction. Her eyes trailed the boys in the back, who had moved to the other side of the four-seater bench and were once again kissing. “I can’t believe they just let those people be like that in public.” She harrumphed, which led to a bout of dry coughing. When she caught her breath, she continued speaking, unperturbed, her bony hand dangling in front of Boris’s face as she gestured in the general direction of the boys. “Parading themselves.”

“You shouldn’t say those things,” Boris snapped, feeling suddenly awakened, as if someone had slapped him. He felt his face flush red as the rush of all the things out of his control came crashing to the surface.

The woman turned to him and said, “What was that, my dear?” The change in her expression was immediate: her eyebrows knotted and her mouth pursed together defensively, a rosebud. Boris felt unstoppable, vengeful. He snatched her veiny hand by the wrist.

“You can’t talk to me that way,” he said through gritted teeth, his voice low and heavy.

“Oh,” the woman said, eyes wide. “I didn’t mean to offend you.”

“I am not your friend,” Boris continued. “I didn’t ask for your opinions.” He looked intently into her eyes, shifting from blue eye to blue eye. He didn’t know what he was looking for. He didn’t know what he wanted.

Like a small dog, she yelped. Realizing he’d been pressing his fingers hard into the flesh of her wrist, he let go. They broke apart, and the woman grabbed her purse while scooting away from him. His eyes darted around the bus. Bubblegum Girl was looking at him with triumphant curiosity. The boys in the back had been stunned into silence. The driver—as if accustomed to outbursts—continued his route without a second glance. The motor inside Boris had quieted, and his body slumped as he felt the weight from within his chest morph into shame.

He hung his head between his knees, gazing wet-eyed into the space beneath his seat. He didn’t feel worthy of the blessing his parents had bestowed upon him at birth—one meant to protect him for life. Ordinariness would never be possible for him.

He didn’t know what he was looking for. He didn’t know what he wanted. *

In his apartment, Boris set down his backpack and placed his house keys on the countertop. He took a long, sober look at their immaculate living room: the rug, zigzagged with vacuum lines; the TV remote, perched on the coffee table, parallel to the Kleenex and a stack of unread books; the throw blankets, folded into bundles and arranged atop the couch’s chunky arm. Every object in its rightful place.

Cleaning was a chore Matthew did only when stressed, so as Boris brushed his teeth—pacing between the bathroom and living room, listening to the loud ticking of the wall clock—he considered the curtness of their last text exchange. They could work this out, Boris thought. All they needed was one evening together. He spat into the sink, and as he rinsed the bristles of his toothbrush with his thumb, he was reminded of how he’d gripped the woman’s wrist on the bus. His father used to handle him the same way.

He shut off all the apartment lights and pushed open the door to the bedroom. There, hunched up in a ball, was Matthew, his curled shape facing the window. Matthew had stayed. And Boris, for once, felt hopeful. He got in bed and gently edged under the covers, placing his hand on Matthew’s cold upper arm before rubbing it to transfer his own warmth. It felt comfortable to communicate with Matthew like this, without words. He could tell from Matthew’s breathing that he was deeply asleep.

Boris rolled onto his back. Somewhere in the world, people were just now waking up. His father was likely already awake, ready to charm his way through another show. He probably woke up every morning next to his mistress and made Chinese crepes for his other kids. Boris waited for the familiar stab of self-pity. But this time, it did not come.