Fiction Short Story

A Working Man And A Working Fool

It’s hot as balls, and we’re pickin’ weeds like some dumb shits gettin’ out last night’s dinner from our front teeth.

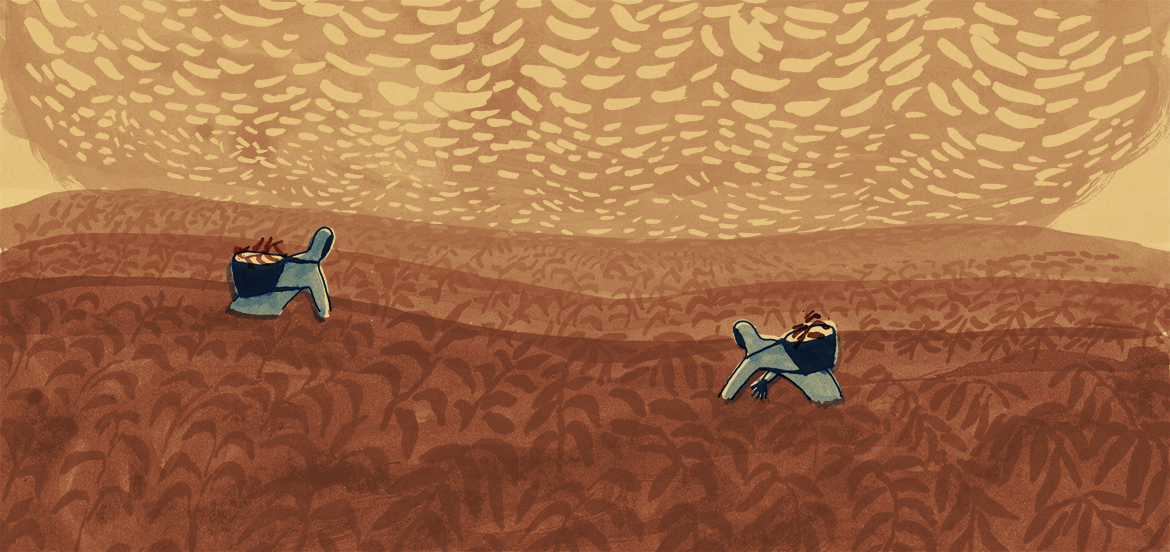

It was the afternoon and their crop-suits were failing. Air was supposed to circulate through the seams so they could breathe right. Not today. The pressure gauge lingered on green (meaning good), but things were feeling more orange, (meaning not so good). Lawnman pressed his face to the ground. He knew the crop was bad, all pale and brittle and clinging to the earth, a few stalks curling up and some falling down. He stood and kicked his tub. “It’s hot as balls, and we’re pickin’ weeds like some dumb shits gettin’ out last night’s dinner from our front teeth. Hey, right, Reno?”

They stood in a field sprayed so thick with pesticide that Lawnman swore the worms would emerge radioactive and mega-pissed. Five heads, ten sets of teeth—those motherfuckers would be big and mad. Stuck in the earth when all the shit hit, spooked up, fat and hungry. Beneath the weeds, the Virginia soil was red clay and baked half to hell. It was a ground that trembled with the specter of death, a ground that could swallow you whole if you went picking in the wrong direction.

“It’s a bad season, you know that, you and I both, champ.” Reno pulled a tissue from his pocket and wiped the shield over his eyes. “Plus, we’re getting overtime today, so that’s an extra round at Kenny’s for the both of us. Dig?”

“I’m not.” Lawnman stood, his bulk swelling against the sun.

“You’re not what?”

“Gettin’ overtime. Are you meanin’ to tell me that the boss man’s pullin’ the skins over my eyes an’ all that too?”

Reno cleared his throat. “You’re going to have to take it up with the boss man, champ. I’m just here to pick weeds. Always follow the good crop, and these days that’s south.”

Lawnman was a big guy, which made Reno, a medium guy, look like a kid in his puffed up vinyl crop-suit. They had been picking partners and housemates for nearly a year, where Reno took care to teach Lawnman things like how to pull with both hands or when to leave the bad weeds alone. Together they traveled down the coast, having abandoned the salt-crusted fields of Maine for the promise of better yield in Virginia.

Lawnman dragged his tub up the row of weeds and grunted. He aimed to take it up, sure, take it up a lotta notches if the boss man aimed to pansy him all across God’s country for half pay.

It was too hot in the weeds and too hot in the suits. As Pickers, they labored blindly in a cheater’s market. Lawnman knew he was a fool in this world of work, harvesting weeds while the boss man just took and took, driving around in his air-conditioned car and barking orders. Lawnman didn’t like being tricked up and ripped off. But that’s what happens when the world goes to shit, when everything normal that once grew stops growing. You do bad work for bad people and just hope to get paid.

At the processing center, Reno once taught Lawnman how to trick back. “Lonny, this is called over-delivering,” Reno said, pressing his boot on the scale that cradled his tub. “This is how you make the boss man happy, even on not-so-good days.”

A little bell rang. Reno dumped the tub of weeds into the churning vat and gestured to Lawnman that it was his turn. Lawnman couldn’t figure how Reno knew this stuff, but when he over-delivered on the next tub, it felt good and new.

“Get happy, boss man,” Lawnman announced, putting his boot on the scale. Then he leaned forward, pushed his weight into it, and gleefully wagged his hips when the bell rang.

*

Clouds were starting to muck around in the sky. Lawnman thought he’d put both boots on the scale today, given the overtime problem, and now the weather. Worse, these weeds were getting tougher as he continued to pick. Some were prickly at the bottom, a few had roots that looked like flesh. Lawnman wished it were yesterday.

Lawnman and Reno had spent last night at Kenny’s, doing Dixie cup Jell-O shots with a bunch of salesgirls in from the north. The girls peddled stock from boarded-up convenience stores and mini-marts. They had a blue car full of dirty magazines, pocket tissues, and soap. A few aerosol cans, gasoline, and a stray puppy they found along the highway.

The girls said they were going south to Cape Canaveral, working the roads while they searched for spacemen who, rumor had it, were drafting plans to colonize the moon.

What do you sell to the working dead? Reno bought tissues and saran-wrapped soap. “For my sweetheart,” said Reno. Lawnman smiled. Reno looked sad. “She’s down south, Lonny. Best boot-tricker in the damn country. All the boss men love her, but I love her more. I’m gearing to see her real soon.”

Lawnman nodded. He bought a magazine and considered the puppy. He’d have to feed the puppy weeds. “It makes you barf, doesn’t it?” Reno had his hand on Lawnman’s forearm. “Why give our crap food to an innocent who can’t say how unhappy he’d be? Better not take him home, champ. He’s safer on the road.”

“Yeah, yeah,” Lawnman said.

Lawnman’s tub was half full, and they had six more tubs piled in the van. Fill was eight: max van capacity. Eight had Lawnman sweating, his body a carrier for disease born from the chemicals he battled all day. Eight had Lawnman at home, not licking or touching or getting anything sticky-sticky until he washed.

“Reno, y’think those girls made it out to where they were headin’?”

“Where were they going again, bud?” Reno picked in circles while Lawnman did lines, so like planets in a broken orbit, their bodies became dislodged. At this point, they were shouting.

Lawnman pointed at the sky. “Up that way. The girls were headin’ to the moon, yeah?”

“No way. Lonny, those girls were just driving down roads. That’s what salesgirls do. They drive down roads and try to sell you on shit and then don’t come back until they’ve got a new thing to rip you with.”

Far away, Reno was a faceless glitch in a pale ocean. Lawnman figured he must look the same way—a strange crag busting up from the broken ground, submerged in the last plants on Earth.

Lawnman paused, looked at the ghost moon above the clouds. He imagined the girls up there. He thought of the puppy in the blue car, chomping on weeds and wearing a spacesuit. He knew he could have protected a thing like that. He knew the company would have been nice.

When the rain came, it came fast, whipping across the sky and turning the ground to soup. Lawnman abandoned the weeds and slid beneath the awning of the bus station, a small structure between the field and the empty road. It’s where they went when the weather got spooked, when the storms rolled in with all that huff.

The rain was brutal, bending the weeds like men hung in prayer. Lawnman looked around, but there was no Reno. He hollered at the field. “Let’s break! Man, you gotta get the shit outta this mess!”

Parts of him were sticking to himself, so Lawnman loosened the pressure gauge. A little air came in, and the arrow moved to yellow.

“Hey buddy-guy, don’ be stiffin’ me in all this shit! The worms get me, I’m just a big snack! You’re all sweet and little like dessert an’ that means they’re-a comin’ for you too!”

The rain hammered at his shelter, and Lawnman worried his voice would be crunched up in the wind. The hell was Reno? Lawnman strained his eyes across the horizon, squinting into the deluge that refused to yield his partner.

The field wasn’t very big. They had picked through about half the weeds, and Lawnman figured they’d get the rest on Monday. It wasn’t like Reno to walk off the job. Had he said a bad thing?

Lawnman stared at his boots, which were sloshed in clay. Maybe Reno was playing a bad trick. Maybe Reno was sleeping in the mouth of a worm, and maybe it was better there anyway. Lawnman’s stomach tightened to a fist as he waited and watched and waited some more.

*

When the rain let up, Lawnman returned to the field and found nobody. He dragged his tub to the van and climbed on the hood for a better view of the field. He turned the key and blared the horn, but nothing would return Reno to him.

Lawnman would be in deep shit if he didn’t report this to the boss man. He collapsed into the driver’s seat and thought about what a person in charge should do.

Lawnman sat very still for a long time. Eventually, he opened the glove compartment and rummaged around. Lawnman found the buzzer in the back, a slab of plastic with a keyboard and a crusted screen. The buzzer was for emergency use only. “Fuckmess this is,” he mumbled. There was no ON button, so Lawnman smacked the buzzer against his knee until it began to hum. His pupils itched with exhaustion. Lawnman wished he could remove them, pop them in little glasses of water.

The sky began to erase itself. By the time the moon became the moon and not just a haunted thing, the van was starting to fill with the smell of rot.

He transmitted one message: “Partner gone, still here.”

Before leaving, Lawnman carved an arrow in the mud and prayed it pointed home. In doing so, he unearthed a grey fragment, calcified, the size of a thumb. That happened sometimes, those bones getting mixed up in the tubs. He flicked it into the field and drove away.

*

Lawnman would never see Reno enter the blue car, the one that doubled back, the one crowded with girls and bound for Florida. But at the processing center, Lawnman did notice a missing tub, a thing much worse than a partner left and gone. It was an under-delivery he fixed by laying his whole body across the scale. The bell rang, and he dumped the last pickings into the churning vat before returning home.

Lawnman’s day off was approaching, filled with nothing, nothing, nothing. On Monday, he would demand his pay. And after a wash, he would submerge his face in the wrong pillow—as though it were a lure—a pillow sweeter and softer and closer to the edge of the bed, and fall deeply into a dreamless slumber.