Don’t Write Alone Notes on Craft

Native Flowers and True Names: Using Research to Write Richer Narrative Fiction

To write her book ‘If You Leave Me,’ Crystal Hana Kim used research to be true to Korea, down to its roots.

While working on my first novel, research is my constant companion. In order to write about the overarching themes of my narrative world—the invisible impact of war on the women who endure, how we pass down trauma within a lineage and language, and the complex effects of colonialism on a people and culture—I need to read texts, pore over images, listen to oral testimonies, and interview family members. All this work is integral to the bookmaking process.

The research I love most, though, comes later. After I finish a full draft, I focus on adding quieter layers of meaning, small details that are important to me but so slight the chances of a reader picking up on them are slim. One example: the plants and flowers that populate the landscape of If You Leave Me .

*

I wanted my book to be true to Korea—a land I love and yet am distanced from—down to the roots, the native plants, the herbal remedies that preceded the prevalence of Western medicine. It was important to me to get these descriptions right, so I began researching the indigenous plants of the Korean countryside. I cataloged my findings in a folder, unsure of how much information I would need.

There were so many stunning flowers—from the yellow-petaled 개느삼 (Korean necklace pod) to the purple-belled 가는층층잔대 (narrow whorled-leaf ladybell). How fascinating to learn that the 참당귀 (Korean angelica) was used to heal “women’s issues.” Or that the 참여로 (black false hellebore) could be used as an abortifacient. As I learned, I found myself doing the work of translation, rolling both the Korean and English names around my tongue, sparking a different part of my brain. This was pleasurable work, new and exciting.

While there were moments when I couldn’t tell if my desire to make sure everything was correct was mere productive procrastination—a way for me to feel good about spending time away from the actual writing—I reasoned that even if only a small percentage of the research entered the story, it would make the narrative world richer, and what didn’t make it on the page would provide me with a deeper foundation of understanding.

What happened next felt like a windfall, an affirmation of my work. While deep in a 783-page document of four thousand species of native Korean plants compiled by the Korea Forest Service and Korea National Arboretum, I decided to read the foreword I had initially scrolled past. In the foreword, the director general of the Korea National Arboretum explains the desire for all of us to be named: “We all want to have a good name, and to be called by a good name.” They reason that the same is true for plants, whose names should provide “not only the characteristics of the plant, but also the ecological value, and [contain] the historical meaning and the national culture of their habitat.”

They go on to explain that due to colonialization, “our plants reflect the painful history of the Korean peninsula,” with their true origins obscured through “names given in Japanese style.” The goal of this document, they assert, is to reclaim these native plants and to share their true names now.

Yes , I thought while reading. Yes. In my novel, I had been trying to show the effects of Japanese colonialization and the Korean War, to explore the ways in which my people had been impacted by outsiders who took away our language and customs again and again. This research affirmed how our history has been formed right down to the literal root, to the trees and plants that grow in our soil. The foreword confirmed that I was right in investigating these topics, in considering the plants underfoot as equally important as the man-made markers of cultural change.

What happened next felt like a windfall, an affirmation of my work. With this knowledge, I began integrating these plants into my book. I decided to link flowers to important characters, moments, and themes to create those deeper layers of meaning. When I needed Haemi’s eldest daughter to make tea for her mother, I chose one made from Korean angelica leaves to allude to the ways in which Haemi may have been trying to remedy her postpartum depression through traditional medicine.

Sometimes, I used the research in tandem with my memories. It’s an old tradition to use 봉숭아 (rose balsam flowers) to dye your nails. I remember staining my own with pressed petals during my summers in Korea, delighting in the fact that my mother and her sisters, and my grandmother before her, had completed this same ritual. In my novel, I had Haemi dye her nails while she thinks about her friend Kyunghwan. Years later, when they are separated by war and grief and time, she will remember a pencil holder she made for him using thread tinted with 봉숭아 petals.

In another scene, Haemi recollects accompanying her mother to a woman’s labor only to find “a thick green stalk dotted with purplish-black flowers,” a reference to the black false hellebore. As she hikes the hillside with one of her daughters and considers how she can achieve a semblance of control over her circumstances, this memory comes to her, and the reader will understand what she wants, what she is unable to say aloud. Always, I am searching for that connection between women and the earth, the ways in which we use the land to protect ourselves.

In a scene toward the end of the novel, Haemi likens her daughters to 할미꽃 (pasqueflowers). The Korean name can be literally translated to grandmother flower , because of its drooping form. I liked that the flower has a fable associated with it, one that is about the consequences of marrying for wealth, which connects to Haemi’s own life story. I liked the idiosyncrasy of Haemi linking her young daughters to a grandmother flower, the ways in which it shows her increasingly unsteady grasp on reality. Sometimes, in my more hopeful moments, I think that Haemi sees her daughters as 할미꽃 because of her understanding of the world, because she can envision them with full lives.

I wrote all of these details in, relishing in their small significances, the ways in which themes reverberate beneath the surface, in the soil. Perhaps no one else would pick up on them, but they would work their way into the reader’s subconscious, deepening their connection to the characters. It is this type of research I love most, which I hope to always bring to my work.

*

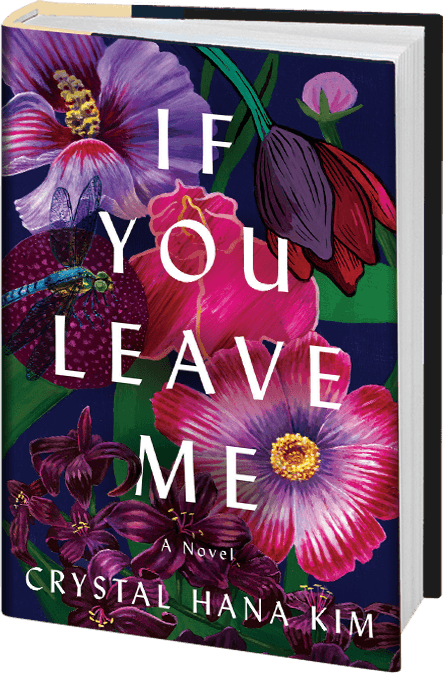

Years later, when I have finished the book, gotten an agent, and sold my novel—in that slim golden space before publication—I have lunch with my editor. We talk about my characters, what the cover could look like, what will come next. I mention the flowers: how I searched for native Korean plants, how they spring up in important moments. How Haemi associates different ones with the important people in her life.

I mention it in passing, but my editor pauses. “There,” she says. “That’s the cover.”

In the weeks following, I send my editor a list of the flowers and their meanings. One day, I receive an email—a stunning painting of blooms. As I take in the image and realize that my book will be out in the world with this face, I am reminded of how important it is to be called and seen by our true names.

Book cover via HarperCollins Publishers