Don’t Write Alone Toolkit

Poems That Will Inspire You to Keep Writing

To celebrate National Poetry Month, we asked authors the question: “What poem or poet inspires you to keep writing?”

There is so much to be inspired by when reading poetry. The canon, ever evolving, is a diverse one. There’s the lushness of an ode, the heartbeat of blank verse, the ways that both tradition and experimentation reward poetic forms, the many possibilities of what surprising language—mere words and letters—can do to ensnare and name the ineffable phenomena of life. Whether a poet is an alchemist or a technician, a seer or a bard, we here at Catapult have a great respect for and admire the writers who can make familiar words sing new songs.

To celebrate National Poetry Month, we asked Catapult magazine authors the question: What poem or poet inspires you to keep writing? Below, the authors share their recommendations and what about these poems, collections, and poets move them to put metaphorical pen to paper. Links to the poems are provided, when available for online reading.

*

Stella Cabot Wilson, author of the essay “After the Family Cabin Burned ” in Catapult magazine and associate editor of the magazine

When I returned to my childhood bedroom one summer during my college years, I taped a copy of Eileen Myles’s poem “Prophesy ” to my bookcase. The language is vibrant, wonderfully inventive, and a little unsettling. See the first lines, “I’m playing with the devil’s cock / it’s like a crayon / it’s like a fat burnt crayon” and toward the end, “my belly is homeless / flopping over the waist of my jeans like an omelette.”

It’s one of those poems that reminds me what is possible to achieve with words—and that I should always dig through the weird metaphors and images gathering dust in some craggy corner of my brain. If you read it, you’ll also see that Myles’s poem is about writing. To me, it encapsulates that hot, energetic feeling of creation. I don’t reach that place every time I write, but it feels so good (and also frightening) whenever I do. If I haven’t been there in a long time, I read this poem to remind myself what it feels like.

*

Hannah Bae, author of the column Gwangju Daughter in Catapult magazine

The poetry collection Cut to Bloom by Arhm Choi Wild inspires me to keep writing about the parts of my family history that I once tried desperately to hide: working-class roots, domestic violence, estrangement from my parents’ culture and, despite it all, a desire to flourish as an artist. Arhm’s words show me that I, too, can try to find beauty and music in the language that describes my most painful—and triumphant—experiences.

*

Ravynn Stringfield, instructor at Catapult and author of the column Superhero Girlfriends Anonymous i n Catapult magazine

This particular line from Lucille Clifton’s poem “won’t you celebrate with me ” truly resonates: “come celebrate / with me that everyday / something has tried to kill me / and has failed” reminds me that writing is my way of celebrating that I am still here. I often try to capture moments with feelings so big and intense that I feel I might collapse under the weight of them, but as of yet, I have not. I am still here. And so I will continue to write.

*

Mina Seçkin, instructor at Catapult and author of the book The Four Humors , published by Catapult

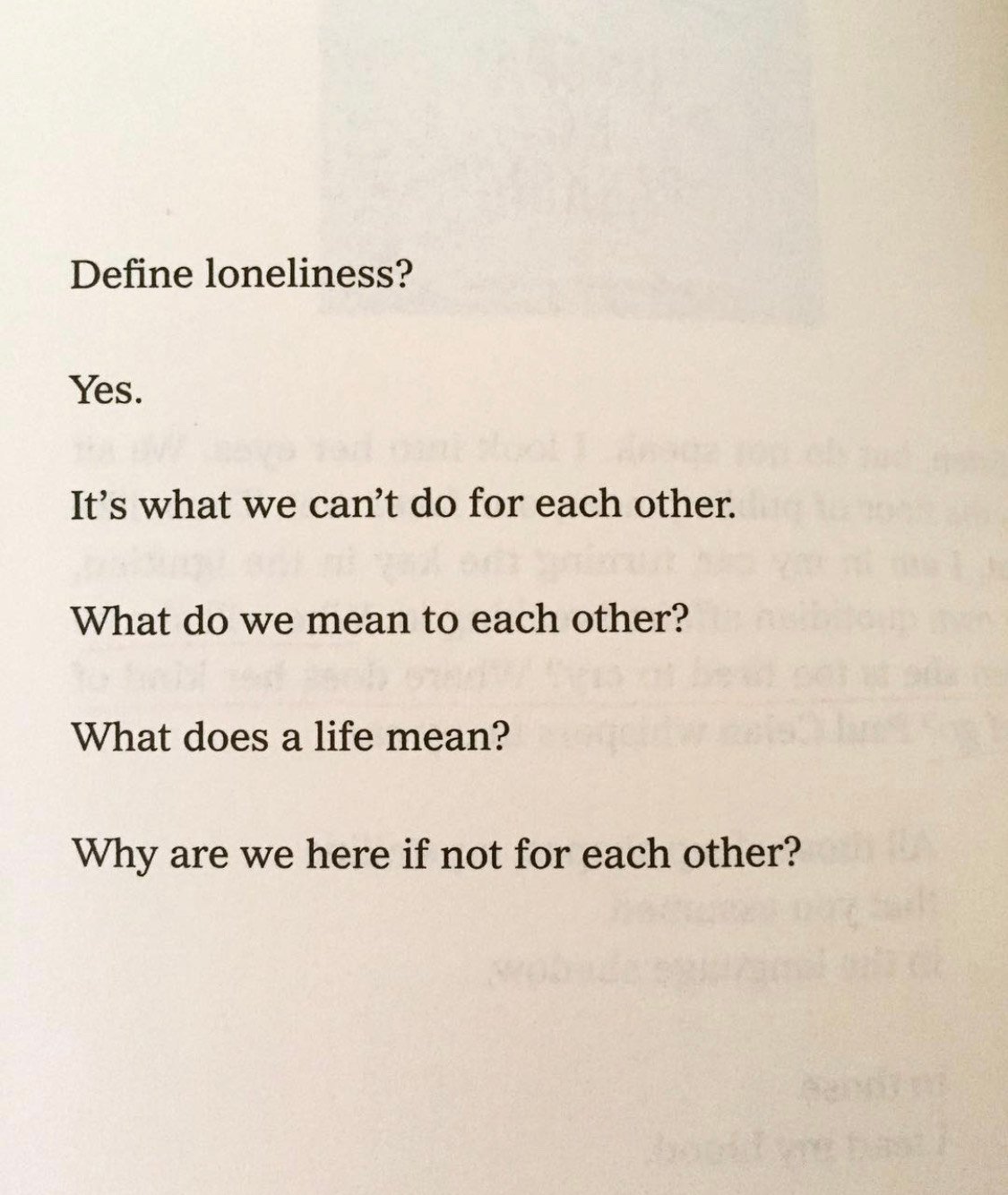

This poem below from Claudia Rankine’s sublime, hybrid collection Don’t Let Me Be Lonely has formed a new and vital organ in my body over the years. Maybe it’s an organ near my heart, maybe near my brain or lungs. These words remind me, always, of why we may continue to exist, how other people aid us through this existence, and how art can and must help, too.

*

Alyssa Lo, intern at Catapult

Franny Choi’s poetry collection Soft Science introduced me to the possibility of exploring the speculative through poetry. At the heart of the book is a series of Turing test poems which take their name from the test used to determine if an AI could pass as a human. Formally, these operate as questions and answers and are just one example of how Choi pushes the bounds of what a poem can look like. Choi’s writing at the intersections of race, gender, and technology helps me consider what it means to write a future that negotiates with the present.

*

Ambika Kamath, author of the essay “Studying the Antlion Taught Me How to Be Human ” in Catapult magazine

When I stop being able to write, it’s usually because I have lost connection with awe. Maybe because life’s other tasks or some inner turmoils overwhelm. When I feel this way, the poem I turn to is a nature poem: Richard Wilbur’s “Crow’s Nests .” I love that in this reading of it, Wilbur calls the piece, “on the whole, a factual poem about the way things look and behave.” Indeed it is, and further, it is a tidily crafted poem that reminds us of secret vantage points that are also where life begins and is tended to. The poem shows me how treasures that are hidden from sight during periods of growth and action can sometimes be revealed only in quieter, slower times. It’s a poem that instructs the reader to look both carefully and imaginatively. For me, that’s where awe begins, and from where I can write again.

*

Ruth Madievsky, author of the column Eldest Immigrant Daughter in Catapult magazine and of the book All-Night Pharmacy, forthcoming from Catapult in 2023

I scream every time I get to this line in the poem “Truth ” by Hala Alyan: “I broke / into the bodies of men like a cartoon burglar.” Alyan is a lodestar for me in learning how to make bold claims in a poem, how to complicate what is “truth,” and how to use musicality and humor to package some truly dark shit like a pill hidden in peanut butter.

*

Lindz McLeod, author of the short story “Elmo’s Struggle ” in Catapult magazine

Whenever I feel uncreative, I read Warsan Shire’s poem “The House ” featured in her first collection Teaching My Mother How to Give Birth . The content of the poem strikes equally hard each time, and resonates with the foundation of my own work; I’m always searching for intimacies, both made and broken, and how those connections impact on people. I particularly like that Shire subverts expectations with the description of her father as a dinner course, an apple in his mouth. It reminds me that power—at least, in fiction—can be simply a matter of perspective.

*

Christine Hyung-Oak Lee, author of the column Backyard Politics in Catapult magazine

When I am depleted, the only act that can sustain me is reading poetry. Li-Young Lee’s poem “The City in Which I Love You ” is one I turn to often. His treatment of silence echoes the silence of not writing. Which then echoes the fact that reading and digesting and triangulating our experiences, all done in silence, are also a kind of writing. The poem is an act of forgiveness.

When I am depleted, the only act that can sustain me is reading poetry. *

Chris Karnadi, author of the column Controller in Catapult magazine

Danez Smith’s Homie reminds me that my writing doesn’t have to be for everyone. In poems like “say it with your whole black mouth ” and “old confession & new ,” Smith is having a conversation with kin. They aren’t opposed to me listening in to the conversation, but the conversation doesn’t need any input from me as an Asian American man. When others respond negatively to my work or I’m tempted to tell my stories with less throat, I remember this dynamic. I write for those I love. Others can listen in, but this isn’t for them.

*

Edgar Gomez, instructor at Catapult , and author of the column Werk. in Catapult magazine and of the book High-Risk Homosexual , published by Soft Skull Press

Kyle Carrero Lopez is one of my favorite poets right now. He has a new collection titled Muscle Memory and his work inspires me to be bolder, riskier, and to pave a path towards liberation by telling the truth, especially when the truth isn’t pretty, like in his poem, “ RuPaul is Fracking .”

*

Richard Chiem, instructor at Catapult , and author of the short stories “You Do You ” and “Mess You Up ” in Catapult magazine and of the book King of Joy , published by Soft Skull Press

When I try to find language again, I think about Fanny Howe . The poem is her vocation. I remember no teacher before her. You can fit an entire emotion on a line break, or a whole life in a sentence, and not look back. I often return to The Lives of a Spirit/Glasstown: Where Something Got Broken Eggs . She taught me how to love a character, to really love a character, with knives at hand and no fear. If I could ever learn to love what I have on the page, I can break you in half, too.

*

Shing Yin Khor, author of the column Curiosity Americana in Catapult magazine and the comic “I Do Not Want to Write Today ,” winner of the 2022 National Magazine Award for Best Illustrated Story

When I am feeling down about my craft, I often look to Cherrie Moraga’s poem “The Welder ” to feel centered and hopeful again. It reminds me that I am capable of making the work I want to make and if I cannot make it, I need to reach out to my community, who also knows how to make it. I owe it to my community to try as hard I can to make our work good and structurally sound. We are so powerful together.

*

Sophia Stewart, author of the column dis/fluent in Catapult magazine

My two favorite poets—Frank O’Hara and Boris Dralyuk —both taught me the same lesson about writing: that specificity is a strength. The subjects of O’Hara’s and Dralyuk’s poems are the people and places that interest them, no matter how niche. They never shy away from a proper noun. O’Hara: Lana Turner, Coca-cola, Bergdorf’s, James Dean, the New York Post, Park Avenue. Dralyuk: Rudolph Valentino, Pasadena, Pacifico Beer, Perry Mason, Cahuenga Boulevard, Julie London.

I have no interest in writing that deals in vagueness, that muses abstractly about love or death or nature without any firm footing in the real and the here and the now. Chances are, if something interests me (a certain actor, a certain street, what have you), it will interest my readers, and the more specificity I use to name, describe, and conjure, the better. That’s what Frank and Boris—devoted to New York City and Los Angeles, respectively, and to rendering their cities in faithful, exacting detail—taught me, and continue to teach me.

*

Jenny Tinghui Zhang, author of the column Why-oming in Catapult magazine

I heard Natasha Rao read her poem “Divine Transformation ” from her collection Latitude at an Asian Debut Writers showcase during AWP, and I was gasping by the end. There is so much reflection and quiet mourning in this relatively short poem—a reminder to me that emotions and the ways we communicate them do not have to be flashy or loud in order to be significant.

Emotions and the ways we communicate them do not have to be flashy or loud in order to be significant. *

Destiny Birdsong, Catapult instructor and author of the column Home/Girl/Health in Catapult magazine

I’ve been listening to this Grammy acceptance speech by Jon Batiste, the composer, bandleader, and songwriter—which, in Nashville, equals poet. I think I love it because it really encapsulates everything I believe to be true about my writing and about art in general: that it’s subjective; that each project finds its way; and that, for me, it’s a spiritual practice that just happens to be readable by the rest of the world. I’d still be making it even if no one else had access to it. Batiste’s speech came at the exact moment when I needed to be reminded why I do what I do, and how I should continue doing it: by minding my own business, continuing to dream, and by competing with no one except my vision of what I can be.

*

Matt Ortile, author of the column Grief at a Distance in Catapult magazine and executive editor of the magazine

I once tried writing a campus novel about boys dating each other at a liberal arts college—while I was a boy dating other boys at a liberal arts college. My thesis advisor was the prolific author Amitava Kumar. I didn’t finish the novel (reading what I have now, it does feel young ), but Ami said I made strides in both style and substance over the course of my senior year. It’s a compliment I’ve since held onto like a talisman. I’m a slow writer and, these days, I doubt myself a lot. I’m anxious about form and genre, about audience, about “seriousness of intent.” That’s why I get stuck on the page. I want to write about intimacy and romance; I get distracted by what others think about or expect of such subjects.

Last year, Ami emailed me a poem, saying, “It made me think of a couple scenes in your book.” I published a book after graduation—different but derived from my thesis project—so I wasn’t sure which one he meant. But because he shared the delicious poem “French Novel ” by Richie Hofmann, I considered the comparison yet another generous compliment.

“French Novel” is sparse, but it’s hot. Like, filled with heat. The poem has this tone that’s both pragmatic and full of yearning. It addresses a lover and gestures toward the milieu of a snowy campus, books in bed, a class intentionally missed: “With boots we trekked through slush for a bottle of red wine / we weren’t allowed to buy, our shirts unbuttoned / under our winter coats.” The voice is almost precocious. The speaker distinguishes between the French language’s use of “the second / of two and the second / of many” to emphasize to their lover that they were “the other, / not another.” It gets at that posture we so often took at school, deploying confident intellect to disguise unbridled want. I love this poem. After first reading it, I smoked a cigarette.

All that to say, Hofmann’s work—both “French Novel”and his latest poetry collection A Hundred Lovers —inspires me to revel in and celebrate that position, that of studied carnality, of wanton restraint. I remember and rejoice: Horny academia is allowed! I’m not sure if Hofmann has ever had to learn to embrace what, in his writing, seems to come naturally. But that’s what his poetry does for me. It gives me permission, encouragement. Though I still overthink, I’m trying to write for myself—with the full-throated and unabashed voice of a gay kid who was “a pleasure to have in class.”

I’m writing a new novel now—about a flight attendant and the men who love him—and I’m excited to revamp that old thesis project one day. I don’t know if it’ll be any better (or any good at all), but it could be fun, just to try. At least, it won’t be for a grade.