Don’t Write Alone Interviews

A Conversation about ‘Murder at Teal’s Pond: Hazel Drew and the Mystery That Inspired Twin Peaks’

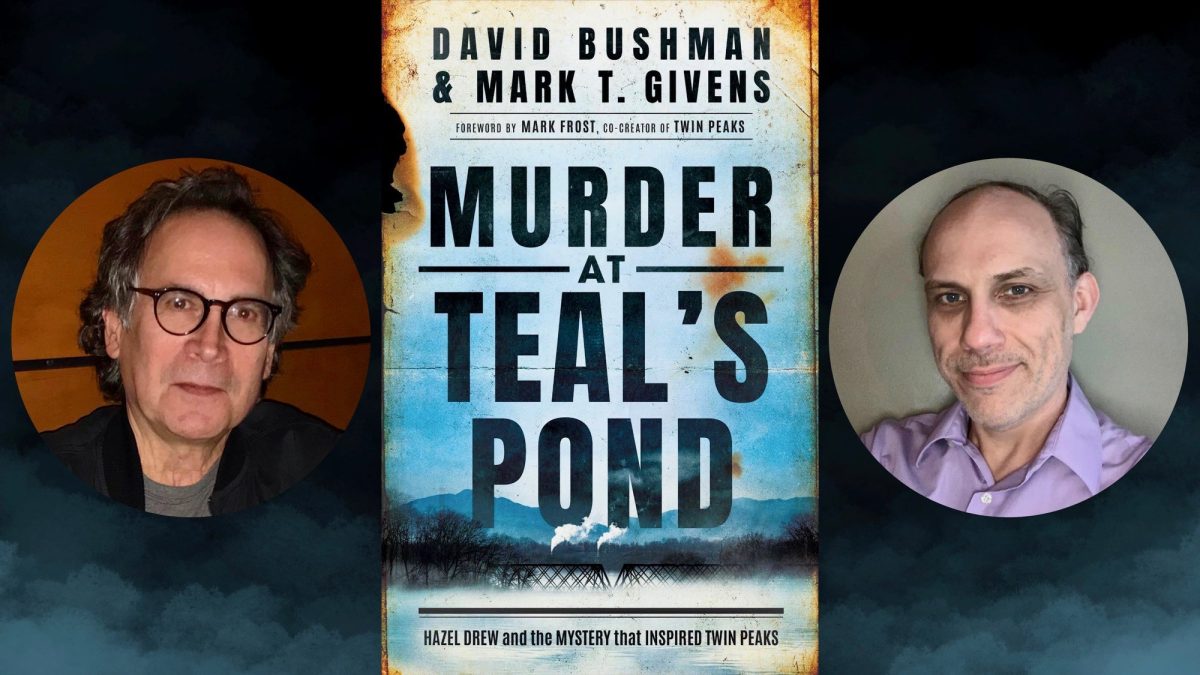

Co-authors David Bushman and Mark Givens talk about their book and how to use research as a tool.

Our 2022 book, Murder at Teal’s Pond: Hazel Drew and the Mystery That Inspired Twin Peaks , revisits the unsolved 1908 murder of a young woman in upstate New York that in all likelihood would have long been forgotten if not for television writer and producer Mark Frost. Frost, born in 1953, vacationed as a youth at his grandmother’s summer home in Sand Lake, about thirteen miles east of Albany, the state capital. In 1990, Frost cocreated, with acclaimed film director David Lynch, the groundbreaking TV show Twin Peaks, which arrived with a bang and departed a season and a half later with barely a whimper, canceled by ABC due to low viewership. But in that fourteen-month period, Twin Peaks developed a rabid fan base that kept the memory of the show alive through annual fan conventions, and Twin Peaks has influenced the creators of some of the most important TV shows to have aired since, including David Chase ( The Sopranos ) and Damon Lindelof ( Lost, The Leftovers, Watchmen ). In May 2017, after a twenty-six-year absence, the show returned for a third season, widely known as “The Return,” on Showtime.

The eruptive crime that sets the show in motion is the murder of Laura Palmer, a beautiful high school coed who appears to be living a charmed life, but in reality in hiding a devastating secret. The real victim’s name, in Frost’s memory, was Hazel Grey. Frost based Laura’s arc partly on the stories his grandmother had told him about the ghost of a young woman who had been murdered around the turn of the twentieth century in the nearby woods, to discourage him from staying out late at night. The murder had never been solved, and so–the story went–her ghost continued to haunt the woods, waiting for the slayer to be unmasked. Something about this story behind the show tugged unrelentingly at both of us, to the point where we couldn’t let go. One of us, Mark, hosted a Twin Peaks- themed podcast ( Deer Meadow Radio ) and devoted several episodes to the murder; The other, David, a TV curator at The Paley Center for Media, heard them and reached out to suggest collaborating on a book. Soon, we discovered that the victim’s name was really Hazel Drew. That was the easy part. We were determined to offer our own solution to the unsolved murder mystery. After six years of research and writing, here it is.

We hope that by sharing some of the more daunting challenges we encountered, we can be of some assistance to anyone out there working on not just true crime stories, but any journalistic or creative nonfiction project requiring extensive research.

*

David Bushman : When we were pitching, book publishers told us that they don’t accept books about unsolved murders. I remember thinking, Really? Have you heard of Jack the Ripper and the Black Dahlia? I think the open-ended mystery actually wound up working to our advantage; we got to play investigators ourselves and were forced into proposing not only what we believe to be a very credible solution, but also one that afforded us the opportunity to deep dive into the monumentally unscrupulous world of upstate-New York politics, a fabulously compelling story in its own right, and one that still resonates today. But my takeaway from that was that if you believe in what you’re writing, don’t let negative feedback from a publisher discourage you. Find another publisher.

Mark T. Givens : Yeah, I agree. Even though a lot of the actual text of the book is a recounting of the investigation into the murder, I would say maybe half of our energy actually went into looking beyond all that research and trying to figure out what the investigation apparently never did: who committed the crime.

So I’d say there were two distinct, but overlapping, phases to our research. At first, we were trying to get down all the basics of the investigation from 1908. This first meant digging through dozens and dozens of contemporary newspaper accounts to pull out and sort through the relevant facts. But beyond establishing this baseline of what went down, we needed to go beyond the investigation to try and determine what was overlooked. What are your thoughts looking back on the research we did for this story?

DB: I spent over a decade in journalism, so I understand the pressure reporters and editors face at a daily publication, but I still was amazed at all the inconsistencies in the reports. I felt a lot of pressure to be accurate and truthful rather than to propagate inaccuracies that have been passed down for over a hundred years. I can’t stress how important it is for people who are relying heavily on newspaper reports–or any secondary or tertiary sourcing–to verify those reports whenever possible, or to at least acknowledge that there are conflicting reports of what happened. In our case, dealing with a murder that was over a hundred years old, verification wasn’t easy, but we used whatever tools were available to us. Sometimes that meant relying on historians and other “experts”—there are so many examples of this, but the one I remember best is when I tracked down a Mark Twain biographer to fact-check newspaper reporter William Clemeans’s claim that he was related to Twain—and the biographer read to me from a letter in which Twin denied any relationship and called Clemens a parasite.

I know that you, in particular, spent a lot of time and energy researching the ownership and history of the newspapers we were relying on, and that’s another thing that surprised me. If you read about the history of the press, conventional wisdom seems to be that the age of the partisan press, when publications were really just subsidized mouthpieces for political parties, had ended by 1908, but what we discovered is that in Troy at least the local press was still extremely influenced by partisan politics during its coverage of the murder investigation, and that all of this reporting had to be filtered through that lens.

MTG: Maybe the partisanship of the newspapers was less overt than in prior decades. We really only stumbled on it because of those inconsistencies you are talking about. Some of those seemed more significant than others. There were certain papers that generally had a good track record of covering the case but which, for some reason, dropped the ball on one solid lead in particular. That seemed really significant, so we ended up working backward to see what was different about those papers.We found out that there were local papers and out-of-state papers, respected papers and tabloids, and some that were owned by powerful Democrats and others by Republicans.

So when we would see articles with strong allegations and innuendo casting shade at Hazel’s character that weren’t found in other sources, it would almost exclusively be one of the tabloids from New York City. Those papers did provide some unique reporting not found elsewhere, but because of that, you had to really pass a critical eye over anything they brought up that we couldn’t find in other papers.

Similarly, we noticed a trend of Troy papers with a certain party affiliation virtually ignoring a pretty big lead in the case. This also happened to be the party charged with leading the investigation into the case. And it should be pointed out that the context for all of this was a city where politics—usually dirty politics–was everywhere and everything. We talked to eminent Troy historians who gave us the context to add some things together, which ultimately helped us crack the case.

What about visits to Troy and Sand Lake and how they informed the book?

DB: There was this dichotomous approach to our research. As you said, we spent days and days and days immersed in 1908, combing through old newspapers in that little room in the Troy library, looking not just at stories about Hazel but also advertisements, weather reports, political coverage—everything we could to transport ourselves back in time. The library is so historic and so atmospheric that sometimes I actually imagined myself back in 1908. But the other really important aspect was the time, we spent visiting Sand Lake and Troy and talking to all these people who had become invested in the case for one reason or another— maybe because they had a familial connection to Hazel or they were born and raised “on the mountain” and had heard stories about her. One person we met—and he turned out to be hugely helpful to us in every way—was Mark Marshall, from East Poestenkill, whose house is on the same grounds as the foundation of the church that Hazel’s family attended. It’s still there. Between us, we must have made ten or so trips up there, tracing Hazel’s steps, visiting landmarks of the case, participating in these “roundtable discussions” that Bob Moore, the Sand Lake historian, set up for us. Those were really fruitful and also really bizarre, right?

MTG: Yeah, just spending time in the area was invaluable. I feel we really got to soak up a lot of the atmosphere in both Troy and Sand Lake. And even though it was more than 100 years later, both of those places in their own way have a certain timeless quality to them, so that if you squint your eyes it still feels like it could be 1908.

Every trip up there was a little different, but they usually culminated in one of those roundtables. These not only yielded great information, they were also usually hilarious, as participants struggled through memories to recount local lore and past family secrets and feuds. We met lots of really cool people and actually had a lot of fun on these little field trips.

One specific story about traveling to the area, which at the time I didn’t think was very funny, involved us trying to get a better idea of the scene of the crime. We had gone onto an old road that was now more of a path behind the pond. We were suspicious that some activity had occurred there and were trying to get a better sense of the geography. Eventually we made our way down the slope to where the dam that created the pond was, and from there, onto the banks of the pond itself. Around this time you had the good sense to say you had seen enough, while I wanted to get a better look from some of the angles on the shore. I think it must not have rained for a while, because you could basically walk (if you wanted to try) on some muddy spots where the pond usually extended to. I was working my way around to get to the other side when I wandered too far into the muddy region and ended up with one of my feet halfway to my knee submerged in what I now realized was quicksand-like mud! Needless to say, once I was fortunate enough to extricate my leg, I didn’t bother with that vantage from the other side.

Do you have any specific memories from the trips or people we spoke with?

DB: I would say meeting John Walsh and Terri Dunworth, John’s girlfriend. We had heard so much about John from some of our contacts in Sand Lake and Mark Frost, since John had helped with some of the details of the case when Mark was first working on Twin Peaks .He had achieved this mythical status, and I was expecting him to be grumpy and disagreeable. But I have to say that John was one of the nicest, warmest, most helpful people we met during the process of researching and writing the book—Terri too. And it makes me terribly, terribly sad that he died so young and never got to see the book.

Mark and I always say we couldn’t have written this book without the insights and assistance of all of the people of Troy and Sand Lake who embraced us, which is ironic in a way, given how much the insularity of Taborton, where Hazel’s body was found, figures in the story. I really can’t stress enough how important it is to devote whatever time is necessary to cultivating sources and establishing a relationship of trust. Part of that is approaching whatever it is you are writing about with an open mind, rather than going in with an agenda and discounting anything that contradicts it. It’s about listening, a hugely underappreciated skill, and also showing people you respect them and appreciate whatever it is they are doing for you.

I suppose to wrap this up we should talk about the process of collaborating, since so many people have asked us about that. I was in New York; you were in DC at the time. Both of us left our jobs at some point during the process. Plus we had the pandemic to deal with part of the time, which made it impossible to even use the Troy library for a while, and I remember when I finally got back in they wouldn’t let the public use the bathrooms, so that meant sitting there going through microfiche all day without a bathroom break, which wasn’t pleasant, let me tell you. But on a more substantial note, we did have editorial disagreements—about some of the characters, including Hazel and Jarvis O’Brien, the lead investigator, and we had to find a way to settle those, and then we also came at this with different ideas about how the book should be written.

MTG : Yeah, I guess it was lucky in a way that it took so long to research the book and sell it to a publisher—it gave us time to work through those differences and find the right tone for the book. More than likely if we were working independently there would be divergences in how Hazel and Jarvis are portrayed. But I think we definitely agreed on much more than we didn’t. And I think we both agree the end result is stronger with both of our inputs.