Don’t Write Alone Interviews

Little by Little, Toni Mirosevich Returns to a Place Where People Are People

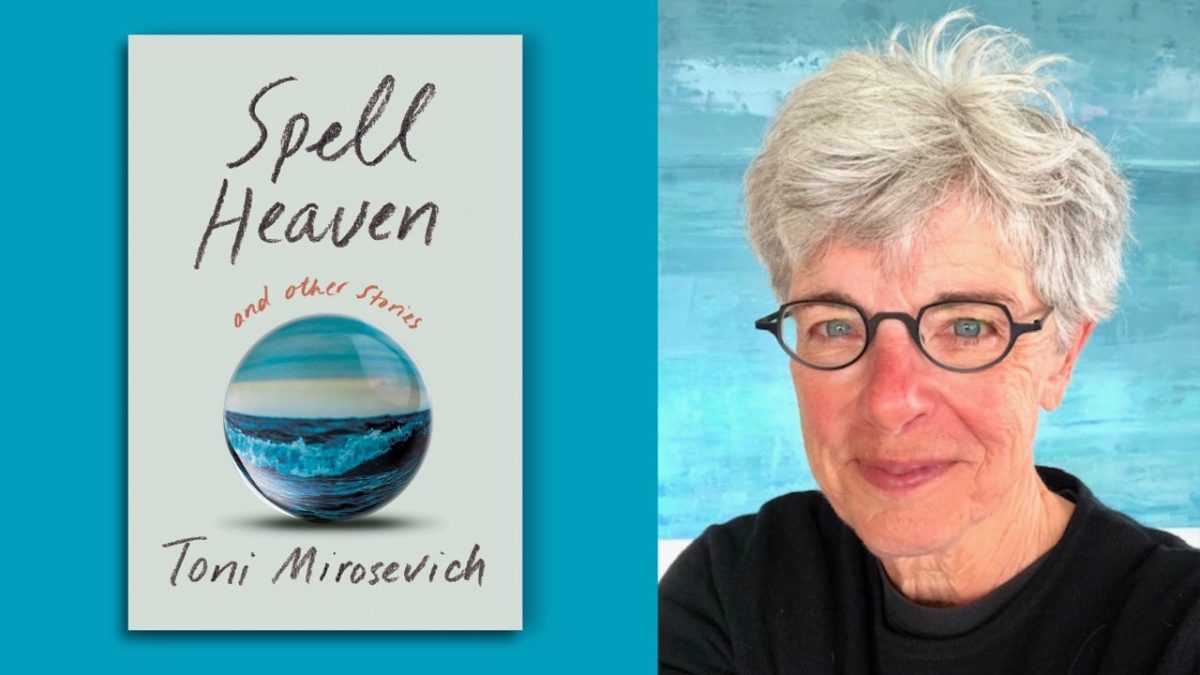

In this conversation, Ploi Pirapokin talks with Toni Mirosevich about her new short story collection ‘Spell Heaven,’ the art of bullshitting, and the fluidity of genre.

While searching for a bench to sit down on with Toni Mirosevich, on the bluffs of Sharp Park Beach in Pacifica, California, it was hard not to draw a parallel between this sunny, windswept shore and the setting for Seaview, her fictionalized beachside town in Spell Heaven: And Other Stories , published last week on April 26, 2022 .

We’d last seen each other in 2015, when I, a neurotic fiction-writing student at San Francisco State University’s MFA program, was dabbling in nonfiction during her Lyric Documentary class. Toni, an inspiring professor and prolific, award-winning writer of insightful lyric essays and poems, kept breaking the fourth wall. She’d bring in stories from outside, from her life, into her lesson plans to make writing real, asking us to consider not only our effect on the reader but whether our writing was making an impact on ourselves.

On Sharp Park Beach, as people ran up with their dogs to Toni like greeting a pink-haired member of BTS, I realized I knew a lot about Toni-the-Generous-and-Gentle-Professor and little about Toni-the-Writer outside of the program. I remembered her speaking about driving trucks once. I’d also heard stories about her Croatian American working-class background. I’d heard most about her draw to the sea. These glittering details surface in each story of Spell Heaven , where we follow a working-class Croatian American fisherman’s daughter turned writing professor as she tries to make a home in a community of “misfits, outliers, drawn to the edge” of the ocean. Where the “laws of the land don’t apply.” Returning to a place “where people are people”—the title of one of the later stories in the collection.

As one of Toni’s students, who heard many of these stories disguised as lesson plans almost a decade ago, I confessed: “Toni, I was shocked at the amount of cursing in this collection.”

“I’m a fisherman’s daughter; every other word is motherfucker !” she said, laughing.

Photograph courtesy of the author

“I suppose you now know my story about fleeing academia to be with outsiders like the ones I grew up with,” she continued. “I come from a community of people who know how to bullshit. There’s an art to it, isn’t there—the art of telling a good story. My father was a great bullshitter. When he was in from the sea he would go to church, and while sitting in the pews, he’d point at someone walking down the aisle, acting holier than thou. He’d nudge me and say, ‘See that man? That guy screws people all day long.’ My impulse to write comes from that world. This is the language I grew up with. Both my parents had limited education. My father never made it past elementary school; my mother reached seventh grade and then left to work full-time in the tuna canneries. Would my mother ever say something multisyllabic, ever use words like transgressive or pedagogy ? If I tried to speak like that, she’d say, ‘Whose daughter are you?’ She also always said, ‘It’s nice to be nice. Work hard. Be nice.’ I used to worry about being too working-class. But, happily, many of the students I taught came from similar backgrounds.”

“Yet your prose is most lyrical when it is most direct,” I said. “Your observation on class is what I related to in this collection. Whether it’s the narrator acknowledging that she has an academic job, or has one of those Italian coffee makers at home, or notices the differences between owning a horse and a home in ‘The One-Second Sandwich,’ she’s conflicted about leaving the life she’s had versus enjoying the life she’s found herself in.”

Toni nodded, looking out across the ocean. “Academia, with its politics and hierarchies, always felt like a foreign world to me. I never felt at home there. Inside the classroom was a different story. Over time I found I belonged in those rooms, tossing ideas back and forth with students. But none of this was planned; there was no set trajectory. I had no idea I’d go from doing nontraditional—for women at the time—physical work to end up in a classroom. I had this plan to continue to be a truck driver, but then I got sick with a chronic illness. I know I’m very lucky to have gotten a tenure-track job after being a lecturer for many years, cobbling together different teaching gigs. It’s a secure, privileged perch,” Toni pauses to wave over a wandering puppy. “But whatever job you end up in, by the sea, you can leave your landlocked concerns behind.”

Photograph courtesy of the author

I asked Toni why Spell Heaven is considered a work of fiction when so much is steeped in realism, particularly inspired by her life experiences and real, living people.

“My definition of genre is very fluid,” Toni said. “I once wrote a piece about my mother for ZYZZYVA and told the editor it was a work of fiction. He said he didn’t think so and published it as nonfiction. With Spell Heaven , I’ve fictionalized people’s names and places and imagined into the lives of these characters. After reading a draft of a story, my friend Patricia Powell once said, ‘What happens if you get closer with the people you are writing about?’ With that smart feedback, I went back into the draft—and now the narrator gets closer to the character by going over to sit on the bench with Tommy (a character from ‘Who I Used to Be’), which helped fictionalize the end.”

She continued, “Toni Morrison once wrote about a similar sentiment in her brilliant essay ‘Strangers,’ where she writes about ‘vaulting the mere blue air that separates us.’ My characters are drawn from real life, but part of what I’m doing in the writing is imagining past my assumptions of who they are. And trying to vault the mere blue air.” Our Toni has herself also written about this concept in more depth for Don’t Write Alone .

“If genre is fluid, then why don’t you consider Spell Heaven a novel?” I asked. “There are recurring characters, one through line, and we’re following a protagonist’s emotional arc in longing to be accepted and finally being accepted.”

“I’ve never thought of it that way!” she shook her head. “There is a narrative arc in finding a gang, a found crew to feel comfortable with, and a slow move to being closer to getting in. It’s looking to be less alone and find meaning. To be in with the out crowd.”

“Is this how the stories came together?”

“Sometimes I wish I had a planned structure. The truth is, I write on the day I’ve encountered someone or something. Like ‘Three Lessons, Four Scars,’ which is about a day on the pier where a man came up with a new definition of happiness. Next time I meet a woman who seems to be on drugs and is hanging out in a parking lot with a young daughter. In ‘The Year of Mercy,’ I start imagining what it might be like to raise a daughter in that environment. The best ideas for stories aren’t planned. The stories came malo po malo (little by little); then themes started to coalesce. I saw that finding community and getting past assumptions became the themes that came back to me.”

Photograph courtesy of the author

I paraphrased “What Diminishes Thee,” where the narrator talks about the cycle of water: “Cloud rains, groundwater flows to the sea and then it all starts over again.” That sentence for me acted as a metaphor for how Toni’s collection is bound together and organized and for the direction we’re taken through the book—in a cycle, wherein we reexamine images, memories, and past lives. It’s one of the things I learned about how writing can progress from Toni, which is to fall into your subjects. Dive deeper even.

“Was this part of your editing process in determining which stories to keep and which new ones to add?” I asked.

“Students will say they hate finding that they are writing about the same thing over and over, but I say, you’re not done with it. You’re circling something that you haven’t finished with. There’s still some mystery there. Some pull. In the book, the editing process—per se—was that stories were added over time. I wrote ‘Murderer’s Bread’ thirty years ago, when I first moved here, after meeting the people in the neighborhood. ‘Devil Wind’ was written in 2014, when I came back from MacDowell and was looking for a place to write. Other things happened through the years; poetry books came out, then Pink Harvest , a book of nonfiction stories. The newer stories you noted, like ‘Who I Used to Be,’ came from sitting on a bench by the pier and seeing my name inked in the wood with other names inked there. Then I knew I’d made it in. It’s an honor to see one’s name on the bench.”

“When I asked you what your favorite story was, you said, ‘Who I Used to Be.’ I was struck by the sentence ‘All of who I used to be is still in here, tucked inside my shirt pocket, tucked inside this skin.’ It actually reminds me of my favorite BTS song, ‘ Ego ,’ which is about how our past selves are a part of our present selves—they led us to who we are. Why is this story special to you?”

“Ploi, when you were telling me about your recent surgeries, I imagined it instantaneously, or tried to imagine what that was like for you, based on times I’d had operations,” Toni said. “It’s immediate, almost involuntary—how you try to find a similar experience from your past to bring you closer to the person you’re talking to. And you’re still carrying all those experiences.

“With these stories, I tried to go beyond my snap judgments that a person is a certain way because of all the things I carried. Do you know who I am? I used to drive a truck. I was married to a man, then found the love of my life with my wife. I got sick and slowly got better. I’m still carrying all of that.”

Photograph courtesy of the author

“When did you know this book was done?”

“I usually consider something done when it’s out in the world. I originally submitted this book to many contests, and it was always a bridesmaid and not the bride, until Jack Shoemaker accepted it,” Toni said. “I was shocked, amazed really. And very grateful. I didn’t have any huge ambitions when I started out and was happy to stay in the moment.

“Along the way, a number of writers were instrumental in helping me complete my drafts. During the pandemic, the Hedgebrook community had alumna write-ins. You’d go and turn on Zoom and tell people what you were planning to work on. It was lifesaving to meet other women writers from all over the country, in this web of silently working together.”

We strolled back to our cars, where I badgered Toni on what other plans she had for Spell Heaven: And Other Stories. What was she working on next? Did this debut fiction launch mean we could expect more fiction from her soon?

“Does this make me a debutante?” she asked.

While I was eager to learn about the future, I couldn’t help but think back to Toni’s teachings, to her writing process, and to the last story in her collection, “Coda,” where we’re reminded to think of our present as an anchor:

“Here’s the thing: you can turn the page forward or backward, your choice, but before your thumb and forefinger lift the page corner there’s that moment—did we forget that moment?—the moment of decision or silence or waiting, the moment where you need to hold on to what you know, or what you have experienced, hold that until you turn the page and start off again, adding to the story, the book, your life.”