Don’t Write Alone Interviews

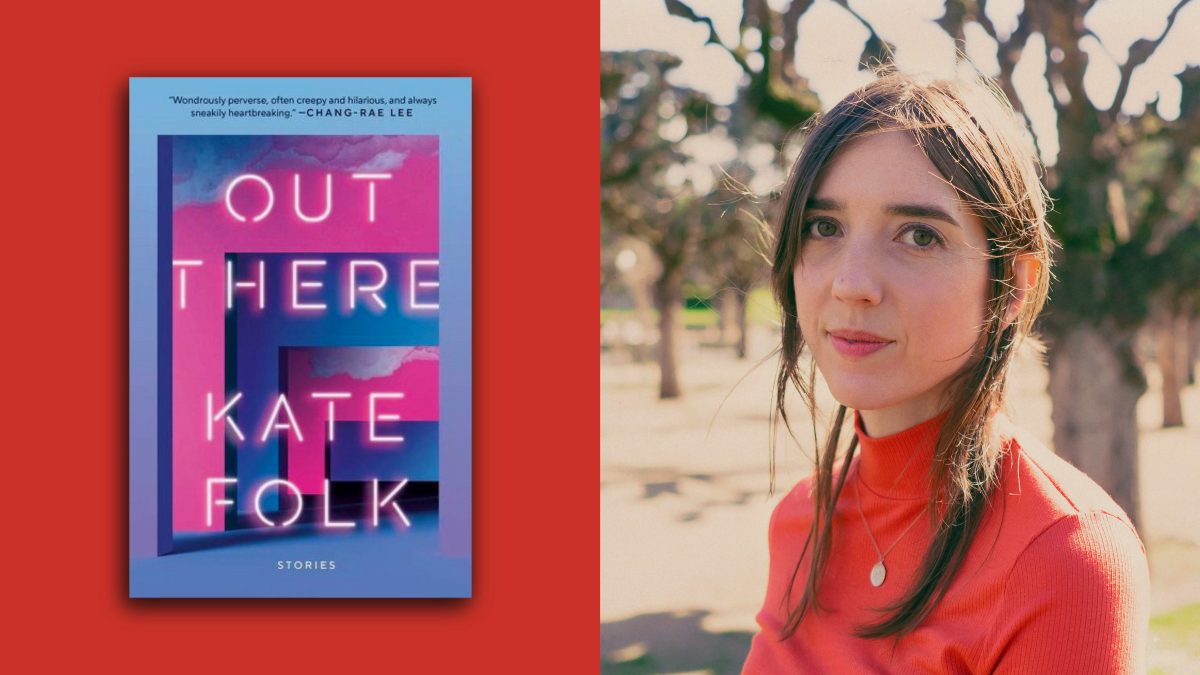

Kate Folk Believes the Weird and Eerie Transcends Genre

In this interview, Ploi Pirapokin talks with Kate Folk about her new book, ‘Out There,’ the importance of humor, and the experience of publishing a short story collection.

In Kate Folk’s debut collection, Out There , which publishes from Penguin Random House on March 29, stories like “Out There,” “The Bone Ward,” and “Big Sur” feature handsome artificial men designed to steal our data, a medical facility for a bone-dissolving disease, and doomed situationships that meet their grisly demise. Peppered with laugh-out-loud cringy yet relatable observations where characters seek intimacy during sex, tender yearnings for acceptance, and a desire to be understood on one’s own terms as a woman, it’s hard to pinpoint the exact equation that makes each story so funny, poignant, and memorable.

Before we order our lunch at Hummus Bodega, Kate extends her arms, saying, “I’m so glad we’re talking on my favorite street—Geary Boulevard.” We’re basking under the sun in San Francisco’s Inner Richmond district, a neighborhood that has cropped up in her short story collection, among other recognizable Bay Area landmarks. While waiting for food, I ask Kate why she doesn’t define herself as a speculative fiction writer, when so much of her stories feature nonnaturalist elements in familiar settings. “Not all my stories are speculative, and I don’t define my writing by genre,” she says. “Some of these stories feature elements of science fiction and horror, and some are based in realism (like in ‘Turkey Rumble’ and ‘Tahoe’), but they are all weird. There’s a strange quality of weirdness I like. I was once staying at an Airbnb and came across Mark Fisher’s The Weird and the Eerie (a book I stole upon leaving) where he defines weirdness in fiction as a quality without supernatural elements, necessarily, but as a mode or affect that transcends genre. The stories I wrote are unified by uncanniness. People are acting strangely even within the realm of realism, and the stories fit together spiritually.”

Photograph by Ploi Pirapokin

Our server arrives and asks if I’d still like my Turkish coffee “on the house.” Earlier, he had claimed they had run out of hot water, so I booed and pouted. As he turns away, Kate whispers, “I think he likes us.”

I say, “No, girl, he is pitying us.”

Quips like these are laced in all her dialogue in her stories. I admire Kate’s penchant for wry self-deprecation, wondering how much of her own experiences resurface in her characters’ voices.

“Humor is so important to me,” she says. “My close friends, boyfriend, and family are funny, and I wanted that to show up in my art. I don’t think you have to be funny to be good, but I appreciate dark humor. It’s a balance to not be too farcical, or it loses its hold on gravity and emotional depth in the work.”

“You do your characters’ justice when capturing their awkward, vulnerable moments of insecurity,” I add. “When they’re rejected, ostracized, and dismissed, you give them space to try to articulate the painful process of coming to terms with their complicity within relationships and social standing. Sure, it’s fun to read about a void sucking the whole world up, but what punctures me are the moments where the characters dissect their actions, behaviors, and regret with such precision.”

“I think awkwardness in a person is a social response. I’m glad my observations about the feeling of uncomfortableness came through. I always think about how something uncomfortable plays out. I felt awkward when I was younger. I was shy and wanted to be more popular in elementary school—”

“Like when you were five?”

“There was this intense social hierarchy there where the popular people were the ones who played sports in the first grade! I just couldn’t fit in. My mom also gave me a bowl cut and that definitely made me not fit in. I thought junior high was where I could make more friends, but that was harder than I thought. My mom had these meditation tapes you listened to as you’d fall asleep, and I’d listen to the ones talking about charisma so that I could somehow absorb that to say hi to this popular (and very nice!) girl I wanted to be friends with. I felt like I was missing this internal understanding of how to say the right things, or that I was missing some weird magic combination to make someone like you. I know now that I just have to be confident and not really care.”

Photograph by Ploi Pirapokin

I could never imagine an uncharismatic Kate. She offers me the last wedge of pita on the plate when we meet at Hummus Bodega, gives insightful feedback on writing and constructive support in bettering my craft—all kind virtues her students have lauded over the years. We had first met at an orientation for a teaching gig in 2016 and ended up writing in adjacent studios at the Headlands Center for the Arts for years afterward. I’ve listened to her type until the sun sets, continuously revising and submitting to publications, never losing her resolve even in the face of countless rejections. “In 2016, I submitted my original collection to my agent with a different title. Looking back, I didn’t think it was as cohesive. Maybe it was longer. We’d given up when it didn’t sell, and I was always told that story collections don’t sell—my agent said something like, ‘barring a publication like the New Yorker ,’—which miraculously happened. At that point, I’d been working on a novel and was editing a new and more curated collection ready to send to contests—not just putting together all the stories I’d ever written but deliberately choosing the ones that fit together. Some of the stories, like ‘The House’s Beating Heart,’ were written in 2013, and I’ve been working on ‘The Bone Ward’ on and off since 2014. I felt taking out stories made this version stronger. Once ‘Out There’ came out with the New Yorker , it changed the game. It created this sense of buzz and urgency, and so we submitted this current collection with newer additions to new editors.”

“But you were prepared,” I say. “If you didn’t have anything to show, they wouldn’t have anything to work with. Did you restructure this version differently?”

“I arranged the stories thematically, opening with the blots from ‘Out There’ and ending with them in ‘Big Sur’ to show an arc about searching to find love and connection. ‘The Bone Ward’ acts as an anchor piece where the character goes after what she wants, and it annihilates her—it is the darkest point of the book. After that, the characters succeed in finding fulfillment in various ways, and ‘Big Sur’ is that manifestation that comes with a cost. I thought about the reading experience and how everything flows together, making sure I introduced new characters and didn’t put two similar-in-style stories together, like two first-person narrators back-to-back. I also included shorter stories to give some breathing room between the long ones—palate cleansers. I wanted to give readers some relief after reading those thirty-page stories, before asking them to enter a new world.”

One of my favorite stories is a shorter one, “The Head in the Floor.” Dismembered bodies, large houses with secret rooms, and the descriptions of loneliness within these empty architectural settings permeate as motifs that reoccur and develop as each story accrues. “What’s your favorite story in the book?” I ask Kate.

“When I workshopped ‘Out There’ at the Stegner, Adam Johnson believed there was more potential with the blots in the story. ‘Out There’ was seen through the perspective of one narrator, and he challenged me in revision to feature more about the blots. But I liked ‘Out There’ as it was.” She smiles. “I wrote a second story that takes place before ‘Out There,’ where this woman Meg dates [an artificial man], and this eventually becomes ‘Big Sur’ at the end.” “After workshopping what you’ve written, what is your editorial process?” “Editing comes intuitively. When I look back at my story drafts, I try to find my themes and bring them out more. Most of the stories assigned as reading in graduate school are by very established writers, so I learned more about current writing by reading literary journals to find what other writers make possible. I found it useful to read writers who were a few steps ahead of me, and I love online journals. Do you remember Roxane Gay’s website in 2012? Back when she was editing PANK ? She was helpful for me to learn how to build a presence with my writing. Back then, there was still a little bit of stigma to being published in online journals, but it’s hard to make your print publication easily available to everyone.”

Photograph by Ploi Pirapokin

Kate’s ability to whittle down her paragraphs to contain only visceral and evocative sentences inspires me, but more than that, it is her tenacity in remaining true to her style. It’s something I think all writers should consider during their publishing journeys. I ask her, “How do you know how to stay true to yourself?” “If I knew how to do things differently, I would! I relied on a feedback loop [at readings, workshops, and publications] where good responses to my stories encouraged me to be more myself. In graduate school, I tried to write more literary fiction, often mimicking someone else, and it wasn’t compelling. What excited me was more weird premises and unfamiliar things. I remember when I was a SF Grotto fellow, I was talking to a writer in the office kitchen who asked me what I was working on and I said, ‘Oh, a story where a woman’s bones have melted.’ It might’ve sounded weird, but it made sense to me.”