Don’t Write Alone Interviews

Kali Fajardo-Anstine Believes Memory Is an Act of Resistance

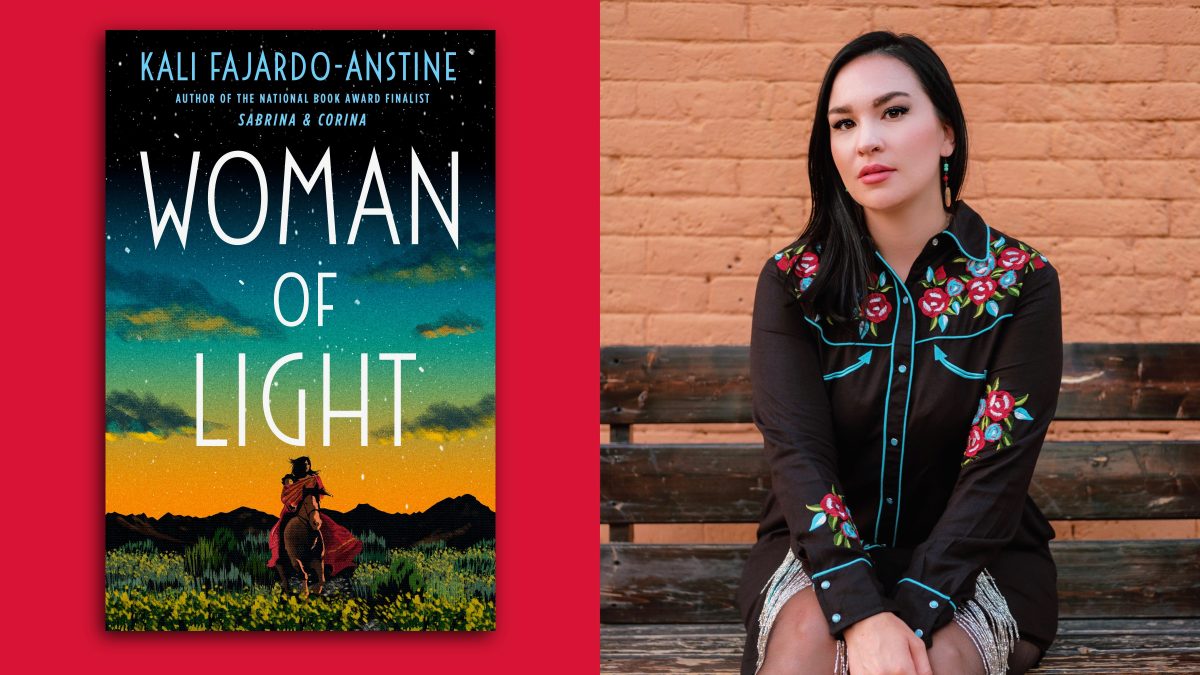

In this interview, the writer Jared Jackson talks to the novelist and professor Kali Fajardo-Anstine about her new book ‘Woman of Light.’

They say not to judge a book by its cover, but it was the cover of Kali Fajardo-Anstine’s 2019 debut story collection, Sabrina & Corina , that caught my eye at my local bookstore and led me to discovering one of the best new voices in literature. Art directed by Greg Mollica, and featuring the pop surrealism of artist Gustavo Rimada, the cover is a manifestation of the Indigineous Latinas Fajardo-Anstine features prominently in her work. The woman on the cover is set in a face profile. A flower, tucked above her left ear, adorns her black bun. As if growing out of the book itself, more flowers caress the woman’s shoulders, framing an open chest and showcasing a final flower painted in saturated colors, the woman’s heart centered atop its stem.

Three years later, Fajardo-Anstine arrives with her much-anticipated debut novel, Woman of Light . An ambitious multigenerational historical novel, the story follows the Lopez family, centering on Luz, a tea-leaf reader and young woman on the cusp of adulthood. Weaving together nearly one hundred years of family history, Fajardo-Anstine guides the reader through an American West dotted with rooibos and plumajillo, filled with Spanish, Tewa, and Diné, and populated by determined, loving survivalists such as the Lopez family.

When Woman of Light arrived at my apartment earlier this year, I noticed its cover also featured a woman, but this time she was mounted on a horse, holding a baby wrapped in a quilt. High grass, distant mountains, and an endless, textured sky cloaks their bodies. In the image, the woman stares off into the distance, to what lies ahead, and with two books now completed, I can’t help but to also look ahead, eagerly awaiting what’s next for Fajardo-Anstine. In late April, we connected over Zoom to talk about Woman of Light , her creative process, the importance of memory, labor movements, and her beloved city of Denver.

The conversation below has been condensed and edited for clarity.

*

Jared Jackson: It took you ten or so years to write Woman of Light. How did you research for the novel—the city of Denver and beyond, the land and its people?

Kali Fajardo-Anstine: The research for this novel began organically, with my lived experience. I wasn’t consciously researching. It came from my childhood and my elders’ homes, like my mother, who’s a storyteller’s daughter. After I graduated with my MFA from the University of Wyoming, I lived in South Carolina. Then I went to Key West, and when I came back, I got a job in Durango, Colorado, near the Four Corners. That’s the closest I ever lived to my ancestral homelands, in what is now northern New Mexico.

While living there, my agent called me and said, “I think you need to do research. You need to learn more about the everyday lives of these characters.” At first, I thought, Well, I know this. This is what I grew up with. But that sent me to the archives. And once I started researching, I realized how little we showed up—as Chicanos of Indigenous descent, as mixed people. I also couldn’t find anything on Filipinos—my great-grandfather’s generation that came to Denver in the 1920s and ’30s. I would run into dead ends. So I began “unofficial research,” where I would go into the homes of elders and ask them questions about their lives. I met all kinds of people across the region; I could’ve researched for years. I’d get excited and rush back to the computer so I could write these scenes. From there, it was about building a relationship between inspiration and what I needed to tell a story that resonated with authenticity and truth.

JJ: Early in the novel, Desiderya, the family’s matriarch, says, “We cannot know the depths of another person’s sacrifice.” The sentence is a fitting motif for the rest of the novel. Can you talk about the role sacrifice plays in the story?

KFA: As an artist, there are several human emotions that I’m interested in exploring, and one of them is sacrifice. I remember being enamored with Faulkner’s speech when he won the Nobel Prize. That being, writers should explore old human truths. He lists love, honor, pity, pride, compassion, and the last one is sacrifice. I was really drawn to that idea, especially for characters like the Lopez family. They’re descendants of an Indigenous line from Pidre and a Mexican line from Simodecea. And Maria Josie is gender nonconforming in a lot of ways. They are an oppressed family through this all—in the different ways that the country is and is shifting during the time. And one of the ways that people who come from oppressed backgrounds gain any footholds generationally is through sacrifice. All these little sacrifices are being made in the novel. I wanted to spotlight and honor that.

JJ: Describing the men of the era, the narrator explains how they treated “a girl’s voice as if it had slipped from her mouth and fallen directly into a pit.” Within a patriarchal society where even the formidable and independent Maria Josie acknowledges that the mere “image of a man served a purpose,” what characteristics did you want to establish for the women in the novel?

KFA: Honestly, they revealed themselves to me. Like Simodecea, the sharpshooting badass who’s cursed by her gifts. Even a woman that powerful and dangerous would have to rely upon men in that time period—for her safety and other reasons. Maria Josie is based on one of my great-grandmother’s sisters. After she came north to the city, she never dated a man again. She only had relationships with women. She started to dress in more masculine clothing. She’s the reason we were able to exist and survive in Denver.

With this book and these women, I wanted to show our worldview and our sacrifices and everything that we did. That our contributions are larger than the oppressive gender roles assigned to us . One of the things I’m trying to do with my books is have radical, realistic representations of humanity.

JJ: Woman of Light is a multigenerational historical novel that takes the reader from the late 1860s to the 1930s. Structurally, the novel moves back and forth across time periods. Did you have a narrative strategy when you began the novel, or did it develop over time?

KFA: The generation I knew in real life was born around 1912 and 1918. They would talk about the generation before—their parents, but also their grandparents. That meant I had firsthand knowledge spanning almost two hundred years. When I sat down to think about the novel and the world I was creating, I realized how far back in time I was able to touch just based on the oral tradition. My ancestors went from living a rural lifestyle—moving from town to town in mining camps, and before that living on pueblos and in villages—to being in the city, all within one generation. I found it fascinating that my great-grandma could have grown up with a dirt floor, not going to school, not being literate, and have a son graduate with his master’s degree from Colorado State University. To me, time was like space travel, and so when I decided on the confines of the novel, I knew it had to be the 1860s to 1930s.

One of the things I’m trying to do with my books is have radical, realistic representations of humanity. That said, I didn’t have a strategy on how to pull it all together. It was a lot of trial and error. Trying to figure out how to guide this machine. I would write scenes that came to me and see if they fit anywhere. As writers, we have to trust our intuition and unconscious mind because it’s doing work for us that we don’t even notice at the time.

JJ: In many ways, the novel, among other things, is a lesson in remembrance. Near the end, Maria Josie says, “Sometimes we go through things in life that are so hard and ugly we’d rather forget than remember, but now I can’t remember very much at all. I regret that now.” How does the act of remembrance function in the novel? What importance, if any, do you put on the intersection between remembrance and storytelling more broadly?

KFA: There was a lot of violence and trauma enacted upon my family for generations, and some members of the family, particularly the men, don’t share these stories. It’s the women who remind us of the heinous t hings they endured. Memory is an act of resistance. But sometimes families force us into forgetting what happened. An attitude of: We’re going to be the bigger people and just try our hardest to make it to the next generation . But the women in my family wouldn’t allow that to happen. They said no. You will bear witness. You will hear about what happened. And we won’t let other groups of people off the hook. Memory, especially for groups of people who are not in the official records, is so important. To maintain our storytelling, to maintain our memories, write them down, and pass them on.

JJ: There’s a point in the novel when Luz is told to shout, “This is my city.” It’s a powerful moment, as Luz finds her voice, takes up space, and refuses to be made to feel unwelcome and inferior on land her family has resided on for generations. Similar to the novel, present-day Denver, its people and landscape and economy, continues to shift. Do you feel like Denver is still your city?

KFA: The novel is dedicated to the people of Denver. I was very particular. I didn’t dedicate this book to Denver. I dedicated it to the people. This is the city I was born and raised in. Denver is still my home. This is where my people are buried going back generations. There are a lot of us, and we might not have the institutional power or money, but we are still connected through our customs and traditions.

There have been a lot of tragic deaths that have occurred in the Chicano community in the past year in Denver. And every time we come together as a community and mourn, I look around and see how many of us there are. It’s almost surreal to think we’re coming together in death, but I’m also realizing we’re this web of people that make the city what it is.

One of the things I think about with Denver is that people like me will be here long after the newcomers leave. That’s what’s happened in all the waves. We haven’t had just one wave of tech or weed people. Not just the silver rush or the radium boom that’s mentioned in the novel. This has been ongoing—a boom-and-bust cycle that’s occurred in the state for as long as it’s been settled. But I do believe it is my city. I don’t know about the future and what’s going to happen here, but this is what happens when capitalism views a group of people as a labor source. Once the labor that was needed is no longer what’s making that state money, they’ll decide they don’t need those people anymore. And so, more broadly, I’m also wondering about the future of our nation and the world. I think we’re going to start seeing more labor movements. And I think in Denver, because of the grave disparities between groups right now, you will see a lot of it.

JJ: You now have two books under your belt. Though they’re notably different, you’ve begun building a body of work with clear connections, among those being a focus on Indigenous and Chicano women, familial relationships, and, of course, the American West. Though recognizable figures such as Bonnie and Clyde appear in Woman of Light , they aren’t central to the novel. With this new book, were there perspectives or beliefs you wanted to challenge? What do you want readers to know about the American West and people you describe in your work?

KFA: When I was coming up as a young person, as a reader, I read voraciously, and there was no depiction of my community—of these Chicanos of Indigenous and mixed ancestry in Denver. It felt like it was saying we didn’t matter. It was saying that the stories of the American West are only stories of settlement, mythical stories of white men finding themselves, of violence that prevailed. It was like living in two realities. Because here I was with all these stories about the people that I come from. About gunrunners during the Mexican Revolution and a great-great-auntie who was a madam at a brothel. All these cool, old, ancient stories, but we were invisible. So one of the things that I’m hoping my body of work does is make our history undeniable. For there to be no way we can be erased from the record and say these people didn’t exist because now we’re in one of the most enduring forms, and that’s the book. I wanted to join this great tradition of literature and make sure we took up space.

You mentioned Bonnie and Clyde, and well, there are all these elements of traditional 1930s Western life in the novel. My characters are American teenagers. That’s something that’s difficult for some people to wrap their minds around. These are American teenagers in the 1930s. They just so happened to come from backgrounds that might not be white American. But they are still entrenched in the culture. And as we’re seeing more and more, the idea of Americanness is vast, and books like this, I hope, are showing how multifaceted we are as people.

As we’re seeing more and more, the idea of Americanness is vast, and books like this, I hope, are showing how multifaceted we are as people. JJ: In a few months you’ll be headed to Texas to be the 2022–2023 Endowed Chair of Creative Writing at Texas State University. What are you most looking forward to, and do you anticipate that your time there will inspire new material that will expand your illustration of the West and the voices you’ve unearthed so far?

KFA: What’s really funny about all of this is that when I graduated college, I wanted to live in Austin. That was my dream. And I applied to library science programs at UT Austin. I applied to the Michener Center. I applied to countless jobs in Austin. And so in this really weird manifested way, I actually get to live in the place I had my heart set on for a long time.

I’m most looking forward to being a professor. I had a difficult time with my education. I dropped out of my first MFA program. I was told that nobody like me gets book deals, that nothing like this could happen for me. I think it’s important to have somebody with my educational background—somebody with a GED, who dropped out of community college, who went to a state school—in these institutional spaces because a lot of my students might come from similar backgrounds. We need diversity of perspective in a multitude of ways. And one of those is institutional. I’m kind of an outlier in that way. I’m excited to bring my perspectives to the classroom and to mentor my students.

As far as new material, I’m working on a new short story right now. My character just left her apartment in East Austin and is flying home to Denver. That’s the scene I wrote yesterday. What’s funny is that when I got offered the job, my dad, who’s a huge supporter of my career and my artistic life, said, “You should start writing about Texas too.” And I said, “What?” And he said, “Yeah, expand.” And I took it to heart. Obviously, I’m not a person from Texas, but this is my region. This is part of the culture that I come from. And I do think we’ll see my work expanding as I live more life.