Don’t Write Alone Interviews

“Race is a construct, yet the impact of it on human beings is very real”: A Conversation with Namrata Poddar

“Instead of engaging with the white gaze, my fiction is interested in exploring the various ways in which our brown communities have endured marginalization . . . ”

Longing for a taste from home in my early days as the only Mauritian undergraduate on the Stanford University campus, I turned to the campus’s South Asian organizations, expecting the steaming cups of chai and Bollywood movie nights to assuage my homesickness. (To a large extent, they did.) The differences underlying the common diasporic belonging to South Asia, however, came as a surprise. I realized that I was different from the Indians straight from Delhi or Mumbai, with their urban worldliness and Olympiad prizes. I did not share the same “in-between” feelings as many of the “Desis” born and brought up in the United States. And I was very different even from the other Afro-Indian students I encountered, whose experiences on continental Africa—Zimbabwe, Kenya, Tanzania—did not mirror my own insular ones.

There are different ways of being brown, I reflected. There are different ways of relating—and of belonging—to the subcontinent.

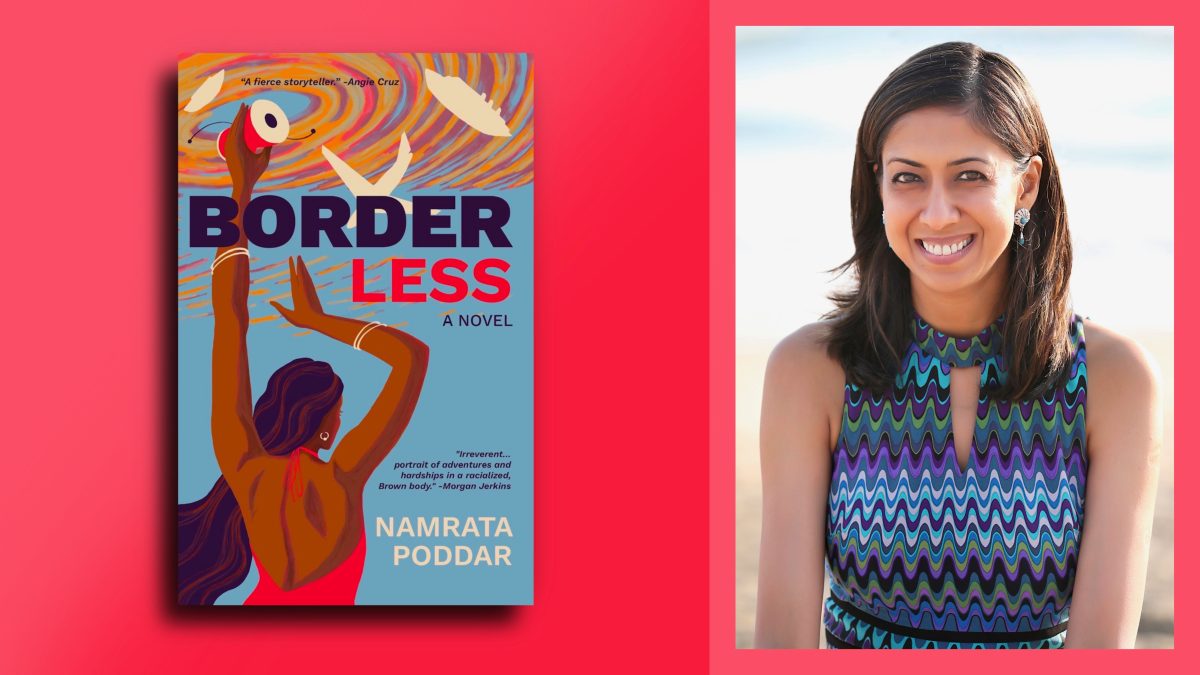

Unsure of quite what to make of this realization, and pressured by the demands of fitting in, I did not probe further into how these different belongings interacted with one another. I buried my questions deep within. Almost a decade later, however, these nuanced shades of brownness burst into life in the pages of Namrata Poddar’s Border Less (7.13 Books, 2022), a literary exploration of migration that brings together characters as endearing as they are complex: the Nepali housemaid who finds subtle ways of rebelling against her employer, the Californian surgeon who tries to educate his mother about sexism while remaining oblivious to his own blind spots, and the young émigré who cannot, despite all her efforts, reconnect with the cousins who remained on the motherland. As it roves across cities and deserts, lingering on the centuries-old frescoes that immortalize the stories of the Thar Desert, Border Less is itself nothing less than a lustrous and colorful tapestry of migration in an imperfectly globalized world.

The author herself belongs to the same “race of wanderers” (54) as her characters. Poddar’s roots plunge deep into various parts of India, such as Kolkata (where she was born), Mumbai (where she grew up), and the Thar Desert (where her family’s ancestry is anchored). Having previously spent time in Mauritius and France, she now lives in California, where she writes fiction, teaches at UCLA, and contributes to Kweli journal as an interviews editor. Poddar’s fiction has been published in venues as diverse as The Los Angeles Times , Electric Literature , and The Kenyon Review .

We engaged in a conversation over email about the process of birthing a novel that seeks the world and more.

*

Nikhita Obeegadoo: Ambitious in scope and global in nature, Border Less is a mosaic of different characters whose lives are entwined in what feels like intricate zari patterns stretching across the globe, from Manila to Boston. You draw striking connections between places as seemingly disparate as Southern California, Mumbai, and Mauritius (77). Could you tell me about the planning and writing processes? Did you begin with a master plan of how these different voices and spaces fit together, or did the pieces of the puzzle fall into place as you went along?

Namrata Poddar: The latter for sure. I’d no intention toward a book, let alone a master plan, when I first started writing Border Less as raw notes in 2004. That year, I’d taken a sabbatical from my PhD program in literature. I was giving myself the permission to simply be with my pen and the page, as opposed to analyzing stories penned by other writers. Allowing myself this freedom was one of the hardest parts of my journey with Border Less because I was training in grad school to become a literary critic, and it was so much easier for me to deconstruct everything I wrote instead of allowing myself to stay with my scribbles and see where they took me. Over the course of seventeen years, those early scribbles in my notebook became individual stories, then a collection of stories, then a collection of interconnected stories, and eventually a novel, one that resists in many ways a conventional understanding of the western novel.

NO: Following the epigraph by Martinican poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant, Border Less does indeed come to us in “snatches and fragments.” You weave a delicate literary chiaroscuro: There is a lot you leave unsaid, and whole sections of lives and journeys remain occulted from the reader’s view. How do you pick what to tell and what to hide?

NP: I’m drawn to an aesthetic of fragmentation that Glissant talks about in his writings. As a brown American mother-writer with desert roots who grew up multilingual in urban, postcolonial India, the idea of silences, gaps, and opacity in one’s story—and history that is mediated by different avatars of empire (patriarchy, capitalism, colonialism or neocolonialism)—makes more sense to me than a story aspiring to continuity, wholeness, and transparency. The latter, as you know, is the driving ideology of the modern realist novel: a predominantly white, male legacy that seeks to not interrupt an implied bourgeois reader’s experience of a “vivid and continuous dream” (to echo John Gardner).

As for what to tell and what to hide, this narrative decision was situational; it depended upon individual moments within a character’s journey as I was writing the book.

NO: In addition to Glissant’s theory of rhizomatic relationality, what are some of the other major influences on your fiction writing?

NP: I see myself as an aural over a visual reader and writer: I am deeply influenced by oral storytelling that is not only our shared global past but also a legacy that continues to thrive in India today, alongside cinematic and “literary” storytelling. Frame narratives and an aesthetic of repetition that make up the world of The Thousand and One Nights , The Panchatantra , or the Jataka tales influence my fiction to a degree. And then, I absolutely love works by writers who consciously import orality into their use of the written word: Salman Rushdie, Amitav Ghosh, Sandra Cisneros, Gloria Anzaldúa, François Rabelais, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Zadie Smith, Patrick Chamoiseau, to name a few. The telling of a story through scenes, when it shows up in my fiction, is influenced by cinematic storytelling omnipresent in both my homes, Mumbai and Greater Los Angeles, homes to Bollywood and Hollywood. Miniature painting and frescoes of Marwari havelis in Rajasthan further impact my fiction, as does Hindu mythological lore that I love. Border Less also takes inspiration from hybrid novels that collapse the borders between long and short fiction: Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street , Cristina Henríquez’s The Book of Unknown Americans , Edwidge Danticat’s The Dew Breaker , and Laila Lalami’s Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits , to name a few. Postcolonial writers who question or subvert colonial modes of storytelling have been the focus of most of my teaching, research, and writing for about two decades, so, consciously or unconsciously, they influence all of my work. This list is long but Edward Said, Édouard Glissant, and Audre Lorde first come to mind.

NO: It is impossible to read Border Less without developing a richer sense of the plethora of meanings that brownness can take, as mediated through diasporic belongings and gendered bodies. You are particularly attentive to “the equations of power and privilege within the shades of brown” (98): Your characters range from a poor Nepali housemaid to American-born professionals and a Mauritian mother-to-be whose life feels like a constant struggle against stereotypes. You also underline the “language of blame” (69) and the particular burden to “adjust” (102) that immigrant women face: As your novel depicts, women sometimes inflict this suffering upon each other and sometimes help each other through it. What does “brownness” mean to you? How do you deal with it differently as a fiction writer, as an academic, and as a brown immigrant yourself?

NP: Well, like gender, class, caste, nationality, and so much else, race is a construct. And yet, as I see it, we in North America are not post-race.

I’m unable to separate my racial identity from my other identities as a writer, an academic, and a migrant. No matter what hat I’m wearing within my large intersectional identity, brownness to me firstly means the awareness of this paradox: Race is a construct, yet the impact of it on human beings is very real: For those of us who aren’t white and are regularly confronted with white supremacy (in the arts, history, or politics), the impact of race is often lethal. That said, much of my nonfiction and editorial work focuses on questioning white supremacy and the aftermath of Euro-American power play over a people of the global majority. My fiction, on the other hand, centers brownness through a global South Asian community. Instead of engaging with the white gaze, my fiction is interested in exploring the various ways in which our brown communities have endured marginalization and the ways in which we reproduce the colonizer within.

I see islands and deserts in Border Less as places embodying rich histories of migration and cross-cultural contact . . . NO: While deserts are often conceived as empty and arid, Border Less reveals them as fascinating locations of artistic creations and migratory encounters. How is the desert connected to the archipelago, the other important geographical realm in your work?

NP: As you know, for the longest time in literature, history, and pop culture (including TV shows and films), smaller tropical islands have been shown as empty lands, devoid of culture and civilization, and therefore “naturally” available for colonization, touristy pleasure, nuclear testing, or the building of large prisons and military bases. Type Guantanamo Bay, Alcatraz, Bikini Atoll, Diego Garcia, or any other small, tropical island on Google Search and the same display of empty, sun-kissed beaches awaiting your arrival will pop up. Two of the most canonical books of anglophone literature are prime examples of this legacy of islands depicted as “barren lands” awaiting colonial penetration: Shakespeare’s The Tempest and Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe .

Much of my doctoral and postdoctoral writing focused on debunking stereotypes about tropical islands and showing them as bustling centers of culture, history, and globalization. And I was drawn to island cultures for two reasons: Firstly, I was raised in the archipelago city of Mumbai, and secondly, my ancestral identity came from the Thar Desert. I related in a visceral way to the stereotyping of islands because deserts often share their history of representation in works by white or Brahmin authors where deserts also stand for “barren lands,” ever available for colonial or neocolonial use. As you can imagine, the impact of this kind of representation is lethal. For instance, when India decided to become a nuclear superpower, it turned to the Thar Desert for nuclear testing and rendered, one safely assumes, an entire region radioactive for generations to come.

This connection between islands and deserts, that is a part of who I am and what I sought to study, unconsciously percolates within my fiction. Like you, I see islands and deserts in Border Less as places embodying rich histories of migration and cross-cultural contact: whether through the Silk Road and the world’s largest open-air art gallery in the Thar Desert, or through the creolized English of Mumbai, or through the transformation of reggae and Indian food in the African islands of the Indian Ocean.

I cannot recommend indie and smaller presses enthusiastically enough to debut authors. NO: Excessive heat and air pollution are omnipresent in Border Less , and throat cancer is woven into the narrative landscape as a symbol of the worsening air quality in many major Indian cities, including Mumbai, where part of the novel is set. Can you elaborate on the environmental concerns in your work?

NP: Most of my writing across genres centers migration, so I see place and displacement as key ideas in my work. Border Less is no different that way, as it tells the stories of different migrant characters who negotiate their relationship to different places across the world. Most of the novel’s characters—Mumbaikars, desert nomads or merchants, Afro-Asian refugees or Indian Americans—experience place as outsiders, when compared to, say, indigenous communities rooted in their land. So yes, how the environment is experienced through the body—the smell, the sounds, the heat, the snow—shows up in my work. Environmental concerns take up space in Border Less in other ways too, ways that are different from a white American environmental writing where nature and culture are often divorced, and where the lone individual accesses self-realization by escaping away from his metropolitan life into a wilderness of sorts. In Border Less , I see nature to be inextricable from a hyperurban world. Nature [in the novel] works as an active participant in the changing forces of history that allows the reader to understand the characters, their communities, and the places they inhabit in more specific ways. In one chapter, Noor, an Indo-African, is hanging out with her American family in a drought-struck Los Angeles, acutely aware of the carefully manicured lushness that surrounds her. What do story moments like these reveal about power, privilege, and geopolitics, or the relationship between nature and culture? Also, what lineage of nature writing do these kinds of environmental concerns bring up for the reader? It’s my hope that Border Less opens up some of these questions about place and ecology, yet in ways that fiction allows us to do, by showing not telling.

NO: Border Less is published by a small indie press, 7.13 Books. How did this choice of press come about, and how did the publishing process go?

NP: As with many BIPOC trying to find a home for their debut books within an American publishing industry that’s known to be 85 percent white at all levels of executive decision, I had a challenging journey with Border Less , although I see myself among the luckier ones. I started a few years back by querying agents, and while I received a prompt, positive response from many, most agents said they wouldn’t be able to place my manuscript with the Big Five, where they had most of their contacts. After the initial disappointment, I knew this to be true too, mostly because my novel is proactively resisting the assumptions of “mainstream” American storytelling, and the closing chapter in this regard is incendiary in calling out conservative literary gatekeepers. So I started looking at university, smaller, and indie presses that are more open to BIPOC voices and stories that talk about political issues without catering to the white gaze or white guilt. My manuscript was a contender for first book awards by three small presses known to champion stories by writers of color, but even these presses wouldn’t actually publish my manuscript. So I kept querying publishers (I must have queried fifty potential homes at least), and at some point, I stopped counting my rejections or even logging into Submittable to see the status of those under consideration. I continued submitting on a weekly or a biweekly basis, and I focused on teaching and freelancing to develop a voice within the community.

One day in 2020, among an all-time low of my professional life (a longer story for another day covering new motherhood, migration, and a global pandemic), I received an email from Leland Cheuk, publisher and editor at 7.13 Books, that he wanted to publish my book. The advance was nominal, and it meant that I was giving away my labor of years for free at a time when I truly needed monetary compensation for my labor. I also knew that indie presses, unlike the bigger ones, don’t have much of a marketing budget and consequently rarely have an infrastructure in place to reach a large audience. That said, here I was with an opportunity to work with an Asian American editor whose latest novel I deeply related to and who had published many writers of color I admire. I sat with the trade-off in my head and accepted the publication offer. And now that I’ve worked with Cheuk for two years over editing and book-birthing, I cannot recommend indie and smaller presses enthusiastically enough to debut authors. Having an Asian American editor who’s also a fiction writer meant that at every point, from editing to cover art and other marketing aspects of the book, Border Less had the space to be what it wanted to be. There was never any need for the book to have to translate its own context and cater to a “mainstream” reader or the white gaze. This aesthetic freedom to me is, hands down, the best gift any “minority” author can have within a larger publishing landscape that is notorious for mediating BIPOC voices for profit, things about which I write elsewhere. It’s a reason I’ll always cheer indie, small, and university presses—and most are labors of love—for the crucial role they play in saving the literary arts from the traps of capitalism.