Don’t Write Alone Interviews

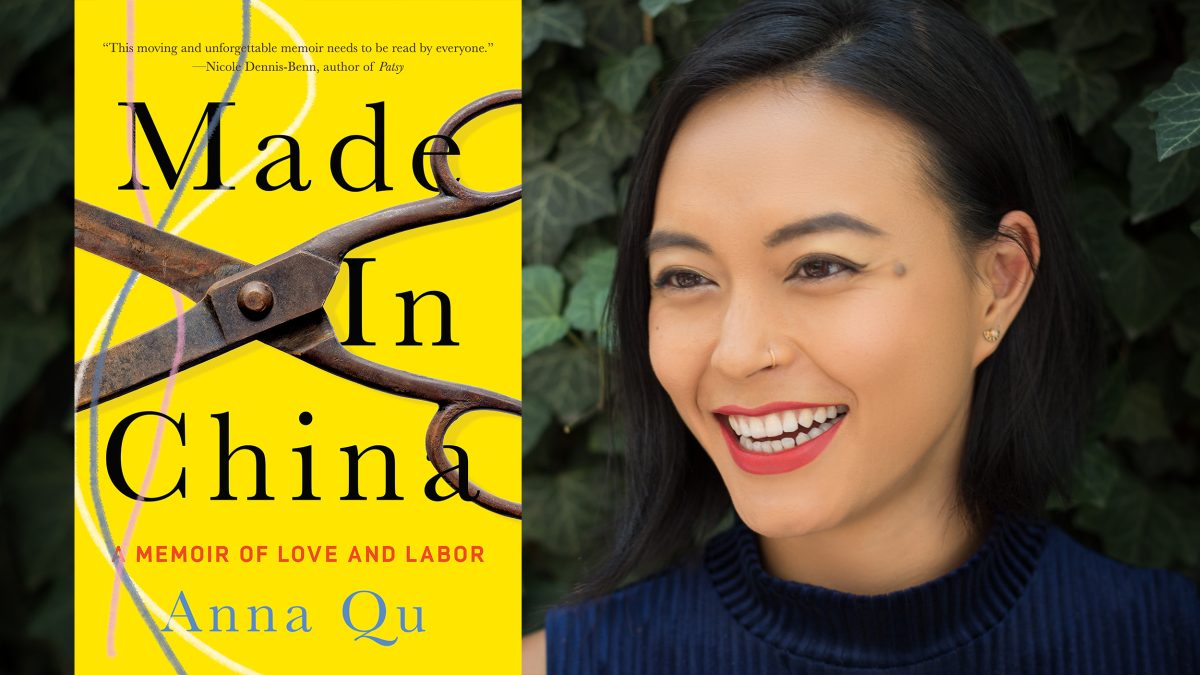

“My personal story needs to give way to something greater”: A Conversation with Anna Qu

“I don’t want the reader to walk away feeling the cruelties that have been inflicted on me; the stake isn’t my personal pain.”

Anna Qu’s debut memoir Made in China describes her relationship with her mother, who leaves Qu with her grandparents in Wenzhou, China, when she immigrates to Queens to work in the garment industry. At age seven, Qu joins her mother—and her stepfather, a factory owner, and her younger half siblings—and must navigate a family dynamic in which her mother, clinging to her newfound middle-class status, resents her daughter as a reminder of the painful past. Made in China depicts Qu’s perseverance through child labor and abuse while empathetically exploring the roots of intergenerational immigrant trauma.

Qu holds an MFA in creative writing from Sarah Lawrence College, serves as the nonfiction editor at Kweli Journal, and teaches at New England College, Sackett Street Writers’ Workshop, and Catapult. In advance of Made in China ’s publication, Anna and I spoke about work, what the “American dream” can mean across generations, and pursuing writing as a “gift to [your]self.”

*

Julie Chen: In the years before publishing Made in China, you published shorter essays, also about your mother and other family members. Did you see the book and the essays as part of the same overall project?

Anna Qu: I spent about ten years on this book. During that time, I held it very close to me. Before I sent it to my agent, only two people had read it. I really wanted to be able to say whatever I wanted, until I felt ready for feedback. [But] the book was such an intense and important project that in the meantime, I needed immediate gratification. So I tried to publish something every year that was more about my life and struggles I was experiencing in that moment. I think it’s important to keep yourself engaged in the writing community, to connect with the work that’s coming out in literary journals.

One of my shorter pieces made it into this book, in a pretty different form from the original essay. But otherwise, my essays and the book are completely separate. I wanted this memoir to be very specific, focusing around the factory and the work that I did there, and my relationship with my family. I also wanted to develop more complex characters than I could in my shorter pieces.

JC: Work is a significant theme throughout the book. You talk about your childhood, being forced to work in your mother’s clothing factory in Queens, and also your relationship with work after you become independent. What made you want to connect your childhood and adult experiences through that theme?

AQ: I’ve had many, many jobs. All because I needed money to support myself. But in the many careers and jobs I’ve had, the one constant was writing this book. Because of the abuse in my childhood, I really struggled with self-worth. If your mother doesn’t love you, how do you love yourself? Your confidence in your family affects the confidence you have at work: your relationships with your bosses and coworkers who end up becoming like family members, whether you want them to or not.

I didn’t write this book just to share the abuse that I experienced as a child. I wanted to look at the culture of abuse, the selfishness of survival, and the complex cost of immigration for each generation. And what having an American dream means to each of us: my mother, myself, and, at the end of the book, I tried to touch on my grandmother as well.

JC: Oftentimes, the American dream is characterized by not just class mobility, but also cultural assimilation. But, in your book, the most significant characters and settings are Chinese and Chinese American. And you define the American dream as particular to each character who has it. When you use the term “American dream,” are you describing something about America itself, the immigrant experience, or the Chinese American immigrant experience?

AQ: I can only speak to Chinese people. We come from so much oppression: the Cultural Revolution, the Red Guard. That oppression has made us reluctant to talk about the past. My mother never took me back to Wenzhou [our hometown in China]. The first time I went back was in 2018. I had never seen a photo of my father. I didn’t really know what the situation was around their marriage, or his death—I still don’t.

Maybe I’m concerned less about the American dream than the immigrant narrative. The traditional narrative is that our parents work hard at a sweatshop or restaurant to give us the best education. Then we feel beholden to them and the pressure of their sacrifice. So we have to thrive financially and work at, for example, a large company that has lots of mobility. But I was fortunate in that my mother married into money, so I grew up in a middle-class family. And it was also freeing to have a mother so cruel that she didn’t care about me at all, so I didn’t have that pressure. At the same time, I felt like I had to support myself. That’s one of the reasons it took me so long to finish this book and to feel like a writer. But my American dream is really about trying to find unconditional love, while my mother’s is stability and safety. That makes our relationship complicated.

Maybe I’m concerned less about the American dream than the immigrant narrative. My mother has a sixth-grade education. My grandmother can’t speak Mandarin, has never gone to school, and cannot read or write. I have an MFA, and I’m currently teaching students the craft of writing. In a lot of ways, that’s indulgent. In the book, I talk about how on each of my adult birthdays, I’ve thought about what my mother was doing at that age, because she had me when she was just eighteen. But it’s unfair to compare our lives to our parents’ or our grandparents’, because our realities are so different.

JC: You’ve described calling the Office of Children and Family Services (OCFS) on your family as a pivotal moment for you. In 2015, you requested your OCFS records and felt shocked by how they characterized your abusive childhood as “unfounded for abuse.” As a nonfiction writer, how do you situate your personal narrative in a broader context, a historical record? What happens when you come across incompatibilities, like you did with the OCFS records?

AQ: I feel like my personal story needs to give way to something greater. That isn’t necessarily true in terms of where I started, or where most nonfiction writers start. I started because I wanted to be heard. But ultimately, once you work on a book for so, so many years, you’re like, “Okay, I’m on year six; wanting to be heard isn’t enough.” I teach a class at Catapult called “Beyond the ‘Me’ in Memoir,” where I talk to my students about what you want your readers to walk away with, what is at stake in your book. For me, I don’t want the reader to walk away feeling the cruelties that have been inflicted on me; the stake isn’t my personal pain. I feel like I am actually very lucky. Maybe writing the book helped me feel that on a level I didn’t feel before.

When I called OCFS on my family, I felt brave. I felt like I had done something huge for myself, that I believed in myself enough to take a stand. In 2015, I was thirty-four, and I still thought it was one of the bravest things I’d ever been able to do, till the moment I read that letter. There were so many errors and inconsistencies. They didn’t even spell my name right. The key fact that really hurt me was that they thought my father was alive. And for someone who has gone through a lot of trauma because my father is dead, I felt like a core part of who I was and why I was having the life I had was silenced. When something like that happens, our immediate feeling is shame. I began to question whether or not what I remembered was wrong. Then I began to do a little bit of research. I realized that a huge percentage of cases reviewed by child services are “unfounded for abuse.” That made me reckon with reality: How many other children were just as abused as I was but didn’t make the cut for what is considered “abuse” in both American and Chinese culture? So this book is also about exposing the cracks in our system.

Part of this book is also about trying to find a place in the cultural differences between America and China. As Chinese Americans, we’re creating a unique history that will continue to grow. The Good Earth was one of the first books I read with a Chinese narrative. It really resonated with me, but it was written by a white woman. With stereotypes of Chinese as “good immigrants,” I felt like I couldn’t talk about what was happening at home. I wanted to write this book for other kids who are going through something that is “other” to mainstream narratives.

JC: You became incredibly self-reliant very young. What has your process of learning how to navigate a writing community and work with other people been like?

AQ: I’ve had a lot of trouble leaning on other people and not feeling like I’m a burden. My latest experience with that was the editorial process, when I had to stand up for sections that I felt were really important but also learn to lean on my editor, my agent—the people that are there to help me. It’s a lifetime struggle: I’m uncomfortable being around a lot of people, but community is important to me, especially because I’m still estranged from most of my family. Meeting my partner was part of what made this book possible. I can’t tell you how much of a difference it is to have one person that helps ground you. I’ve been let go and laid off multiple times and have panicked about my ability to support myself and pay rent. Even after I finished the book, I needed to be in a stable place in my life to go through the publishing process. I try to be vocal about how scary this process was, because I want there to be more support for other writers.

JC: I’d love to hear more about the moment you decided to pursue writing, like when you got an MFA. How, if at all, did that choice relate to the experiences you write about in the book?

AQ: I chose to get my MFA because I wanted to be more confident as a writer. I also wanted community. As I was learning to love myself, it was a gift to myself. I was very aware that I wasn’t necessarily going to get a better job afterward. But I wanted to give myself those two years. I was lucky in that I didn’t have to support anyone; I don’t give my mother money. I’m just by myself, and I can do whatever I want as long as I can take care of myself.

I’m really grateful to this book: It felt like a vocation, instead of a choice. It didn’t let me go. And at my lowest points in my life, it was the thing that felt most important to my life and the thing that set me apart. There’s nothing like writing for me.

I’m really grateful to this book: It felt like a vocation, instead of a choice. JC: In the book, you discuss the different roles Wenzhounese, Mandarin, and English have played in your life. You grew up speaking Wenzhounese with your grandparents in China, with whom you were very close. But once you came to the US, it became the language your mother spoke with you, a language of discipline, cruelty, and abuse. At the same time, you spoke Mandarin with her family and learned English in school. How has your relationship to those languages changed since you’ve become a writer in English?

AQ: Wenzhounese has always felt like such a private language to me, because it was the only language my mother would speak to me, and she refused to speak to me in Mandarin. She said that she didn’t want me to forget Wenzhounese, but it was also problematic because it meant that she never spoke to my half siblings and me at the same time. The language isolated me: another form of punishment for my mother. I learned Mandarin, but I had to be very proper, because it was the language I spoke with my stepfather and half siblings.

My mother’s view of English was that I was very lucky to learn it. When I was nine or ten, she made me start taking the bus to Flushing. I was so afraid, but my mother said that I would be fine since I knew English and had the money. She’s right in that having that skill gave me freedom. I always felt that education and English are some of the only things I’ve had.

Now, looking back on my relationship with Wenzhounese and Mandarin, I’m looking for a way back in, a connection. I don’t speak to anyone but my grandmother in Wenzhounese. I have randomly found an expat community of Singaporean friends, who I sometimes speak Chinese with.

JC: What are you working on next?

AQ: I would love to write fiction, just because this book has been so personal. And I want to enjoy some of the writing process a bit more. In the next couple of months, I’m doing character research. I’m currently reading a book, The Making of Asian America . I’m trying to understand our history from an Asian American perspective and set a story within that frame. But I think I will always be a nonfiction writer. As I write the novel, I’m sure I’ll publish nonfiction.

But it’s been hard thinking about the second book while waiting for this first book to come out. With book publishing being quiet during the pandemic, I’ve had to maintain my expectations. But now I feel a reprieve. I hope that as the book comes out, it can really spark some creativity and provide some momentum for the next project.

*

Anna is teaching a 12-month online memoir generator for writers of color with us, starting this fall. Learn more and apply here .