Don’t Write Alone Interviews

Liz Harmer Is Working Out Thorny Moral Questions

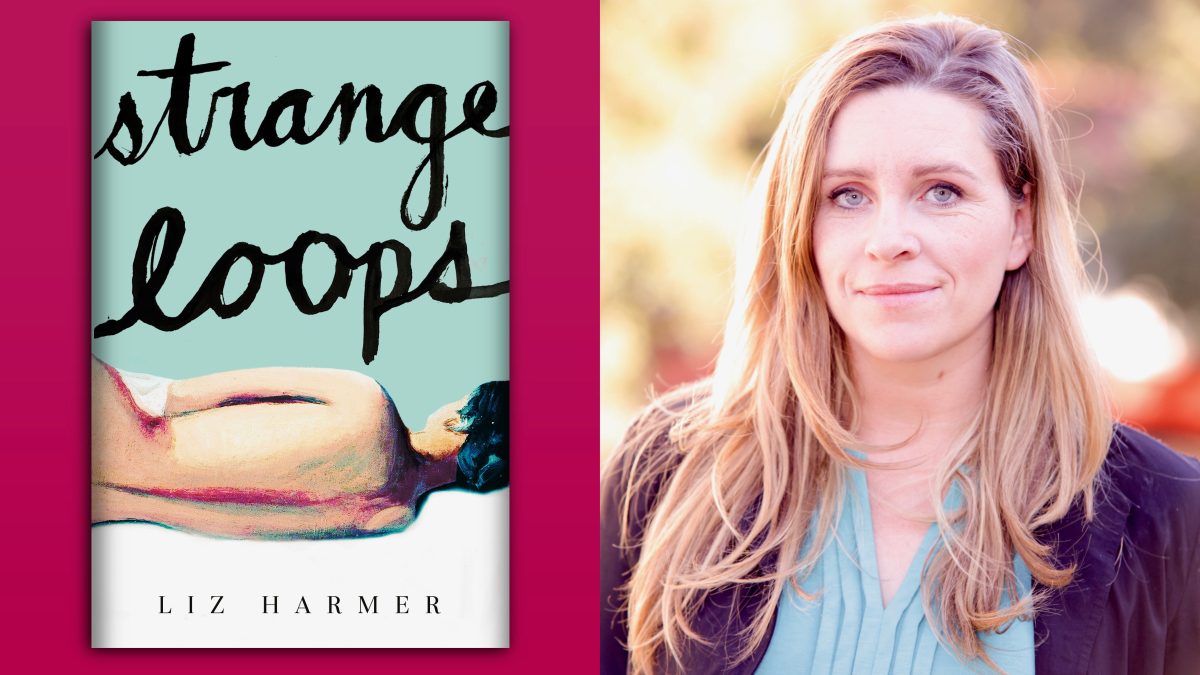

Jean March Ah-Sen interviews Liz Harmer about her new novel ‘Strange Loops,’ crises of faith, and the mysteries of existence.

How can one “disperse the terrible vapor of guilt?” This is the question at the heart of Canadian writer Liz Harmer’s novel Strange Loops (Knopf/Vintage), the follow-up to her Amazon First Novel Award–nominated debut The Amateurs . Strange Loops is a dizzying freefall into the worlds of religion, motherhood, and infidelity. Francine’s bond with her twin brother Phillip is tested when Phillip finds God during his teenage years. When Francine falls in love with the married youth pastor in charge of Phillip’s church—and her attentions appear to be reciprocated by the older man—Phillip experiences the kind of distress unique to a religious crisis.

Many years later, after settling into their adult lives and starting families of their own, Phillip resents Francine and blames her for robbing him of his faith. When he begins to suspect that his sister is engaged in another extramarital affair, the twins become locked in a pattern of disastrous behaviors that threaten to sever their connection permanently.

A lecturer in creative writing at Chapman University in California, Harmer tells me that the novel emerged from her desire to create an intelligent story “without ironic or omniscient distance,” and to portray characters with “so much immediacy that I could somehow not have distance from them.” As an exploration of the unpredictable tumults of morality and desire, Strange Loops follows in the footsteps of books like Saint Augustine’s Confessions or Béatrix Beck’s The Passionate Heart . Strange Loops contributes to this tradition by showing how an individual’s moral investigations can enhance or complicate romantic attachment. It renders, with great vividness, the failure to “live well in a conventional domestic arrangement.”

I corresponded with Harmer to discuss the elusive nature of forgiveness, the boundaries of madness, and the immobilizing social pressures women experience when they are perceived to err. Our conversation has been edited for clarity.

*

Jean Marc Ah-Sen: The sexual politics at work in the novel are complex. Francine begins a relationship with an adult while she is a teenager, and then with her own student when she is teaching at a university in her thirties. Francine is positioned as both victim and victimizer. Why was it important for you to have a protagonist who was capable of slipping in and out of these identities?

Liz Harmer: This goes back to one of my deepest beliefs about human beings—shaped, I’m sure, by the religious framework in which I was raised—that everyone is capable of being both victim and victimizer. One thing I’ve been thinking a lot about is the idea of innocence, not as in guiltlessness but as in unknowingness. How you can be innocent and do harm. Psychopaths are not the only people capable of doing, for lack of a better word, evil. And I think there’s something underexplored about power: how, in order to know you can do harm, you have to believe you have some power over others, and how there is some danger in a sort of charismatic innocence.

In Francine’s case, she is desperate to believe that she is not a victim—the novel knows she is, and she doesn’t—partly because she finds comfort in believing she was in control and had agency.

I think that a novel is an ideal place to work out thorny moral questions, as well as hypocrisies, because we can see ourselves there: as people who are capable of doing harm, and also as people capable of being harmed. Limited people on earth in bodies.

I think that a novel is an ideal place to work out thorny moral questions, as well as hypocrisies, because we can see ourselves there. JMA: You describe Francine as a kind of “anarchic cynic” and as someone who has a desire for self-annihilation. Francine is aware that engaging in an affair in the throes of motherhood and while running a successful business with her husband threatens to upend her life. Is her decision to be unfaithful based on her temperament, couched in unfulfilled desire or trauma, or, as Francine herself suggests, an inevitability that is likely to incur the wrath of God?

LH: She wants her life to be upended; she is struggling to accept the ordinariness of life. At a certain point she realizes that the thing she really wants is to be lifted out of her daily life and into something “real” or “eternal,” something like true intimacy. I suppose it’s hard for me to articulate this because to me it is the mystery in the novel that remains, and this sense that there’s another order of things underlying the narratives by which we live is really a sort of madness or mysticism that is beyond language. The desire for self-annihilation—this sort of terrible path she puts herself on—is motivated by something unclear to her until the end: She doesn’t recognize that she’s acting out the role offered to her by her family, and her trauma, and her temperament.

JMA: Francine’s PhD dissertation involves a biblical passage in which Mary Magdalene—one of Jesus’s followers and, in some interpretations, his consort and lover—wanders through a garden and is visited by the resurrected savior after his crucifixion. Francine returns to this scene many times during the novel—what is it about this piece of scripture that provides her with so much spiritual sustenance and guidance?

LH: Mary Magdalene represents a combination of sex/love/desire with intellectual and spiritual thirst, which gave me solace when I was a young believer, and which is the kind of solace Francine needs too.

Many years ago, I did a master’s thesis on the figure of Mary Magdalene in medieval and contemporary texts, and while I was in the middle of losing my faith, this resurrection scene remained the passage that most moved me. Later, I thought I’d revisit this for my own PhD dissertation (before I dropped out) because there is a throwaway line in Foucault’s Discipline and Punish that refers to the noli me tangere , which is the Latin name for this scene. Since I was never going to write that thesis, I gave it to Francine on a whim.

Both the figure of Mary Magdalene and this scene [have] to do with the desire to touch and the impossibility of touch—a bodily desire that can never be met. Much of the novel [asks] after the extent to which people are separate from each other, and the desire to touch/be intimate and the command that one not touch/have a boundary. In this way, acts of sex became places to attempt (and fail) to experience a thing that is divine, and bodily, and fleeting in the way this moment in the garden is.

JMA: The novel could be described as being about losing one’s faith, or the search for meaning that can replace this loss. Do you think that this rupture is at the root of the problems that Francine and Phillip seem to be experiencing, albeit in different magnitudes?

LH: Yes, and this is a very personal sort of rupture for me. I had been what you might call a true believer, and it took me a very long time to really lose every last trace of my faith. We’re talking years, maybe over a decade. And while I have a strong desire for there to be a larger meaning to our lives, I have a stronger desire for that meaning to remain out of reach, for the mysteries of existence to provoke awe. So I have sympathy with characters on a quest to have faith and to find the kind of meaning that religious or spiritual beliefs can provide, even while I can’t really play at this in a lighthearted way, or I couldn’t while writing this novel, which I did in the final stages of my own crisis of faith. While sometimes this crisis felt unendurable—I was mourning, and I had pretty terrifying insomnia for several years—once it was over, the place where it left me, where many ideas and phrases no longer moved me, where I was no longer interested in certain arguments that had once been so charged, was a much more depleted place. I felt I was looking back at a home I would never again be able to enter.

JMA: You’ve said that the book is an examination of how scapegoat dynamics in the public sphere can become intertwined with misogyny. Why did you feel that this subject matter could be the basis on which to structure a novel? Do you view the book as a Me Too or post–Me Too novel?

LH: Me Too happened after I’d written much of a first draft, and, like many others, I found myself reevaluating many things that had happened to me—what I had internalized and accepted. And then I looked at this novel I was writing that was about sexual power dynamics, in which a woman doesn’t understand herself as capable of being victimized, and that there is something about her—she believes—that makes her deserve her ill-treatment. So the sexual politics of the novel for me were partially a stand-in also for what happens to a person who fills a scapegoat role in a family or a culture, and I’ve always found this as a psychological mechanism really fascinating: If we can’t bear to live with our so-called sins—if we can’t bear to live with our shame—then in order to live, we have to put those things somewhere else. So you blame someone else, call your sins their sins, and send them out into the wilderness. In Francine’s case, this dynamic emerges partly with what happens between her brother and her youth pastor. She’s seventeen, she is sexualized and then victimized by an authority figure, and not only does she believe (for the rest of her life!) that this is something she did to him , but her brother believes it is proof of some rottenness in her and that she also did it to him .

I had been what you might call a true believer, and it took me a very long time to really lose every last trace of my faith. JMA: You use a kind of dual structure in Strange Loops that alternates between the twins’ emotional and spiritual trajectories, often examining the same events from both of their perspectives. What were the advantages of writing a story that would be presented “in stereo”?

LH: In an early draft, my editors and I found that I had overemphasized Francine’s perspective—maybe a problem in a book that’s meant to be about a twinship that has such flimsy boundaries the twins can’t really make sense of themselves or their lives without the other. I was trying to explore this thing about consciousness, how Francine and Phillip cannot be disentangled, how they are sort of one single entity. As a writer, I needed to understand Phillip more than I did at first, and to take seriously the anguish he felt instead of—to go back to the question of being a victim and victimizer at once—seeing him as more purely a villain plaguing Francine. It’s also so fascinating to uncover someone else’s very different perspective on the same event, and this [drives] me to empathy and humility.

JMA: You are known for doing exhaustive research in preparation for your books. Can you describe how discovering the shared terrain that your projects will occupy is conducive to your writing process, or helps to clarify the shape and form that a book might take? Strange Loops seems to be at least in part a conversation with Roland Barthes and Anne Carson, for example.

LH: Rather than as research, I thought of the reading I was doing in tandem with Strange Loops as feeding the source, the energy from which the book arose. During the first draft, I had a playlist and a set of books that I’d return to in order to conjure the mood I needed to be in to write with the kind of unrelenting intensity this book required. Only now as I’m answering your questions do I see how much this mimics what I used to do in church: a hymn, a reading, a hymn, a reading, a prayer. So I read and reread the Barthes, for example, to sort of lower myself into that mood. Another text I used toward the beginning was Madame Bovary . This sentence guided me: “She loved the sea only for the sake of its storms, and the green fields only when broken up by ruins.” Lots of poetry, I picked up and discarded. A line from Mary Szybist’s “The Troubadours Etc.”: “At least they had ideas about love.”

Anne Carson’s Eros the Bittersweet helped me see that eros drives intellectual and artistic inquiry as much as it does romantic love—that what is erotic is the sense that there is something just beyond your understanding. A very close friend of mine, a Hegelian philosopher, was also writing about desire, and she’d give me things to read as well, and for a while it was a total preoccupation. I read Sula by Toni Morrison and saw it through this gauze of erotic questions, for example, and I’d feel bored if anything I was reading didn’t touch on these interrogations. Until I didn’t anymore! Like a marriage, I domesticated it.

JMA: You had a Calvinist upbringing, and I am wondering if this religious structure in your life—regardless of whether you are writing explicitly on religion or not—has found its way into your writing endeavors. Did religious instruction help to develop your skill as a reader of meaning and metaphor as much as it did your abilities as a writer?

LH: Calvinists are very textual. I was always having to memorize verses for school, which I’m sure was good for my mind, and a sermon was nothing if not an opportunity to squabble over the placement of a word here or a word there and what the emphasis of a word might mean. The syntax had life-or-death consequences! Also, I was forced to sit in church without any distractions, and those were times I entertained myself by telling myself stories, or I puzzled over words that the minister was using. One minister we had used the word turmoil all the time, and I used to turn it over in my mind as though I could figure out what it meant just by thinking about it. So some of these phrases will return to me, and so much of the language of scripture is just incredibly beautiful. I try to reread the book of Job and find that instead of reading it, I want to ingest it. This early training [taught] me to love poetic language and stories for the rest of my life, and the value of memorization and rereading.

JMA: The book you are working on now is a memoir dealing with the overlap between religion and the “boundaries of madness.” You’ve been quite open about your hospitalization as a teenager and the mental health challenges you have faced. Can you describe this project and how the book might differ from your novels?

LH: Yes, the memoir is called Interpretation Machine , and in it, I bring together my own history as a kind of case study, with research into psychiatric history as well as interviews with family members. I wrote it to understand what had happened to me, because while I had a textbook experience of manic psychosis, I have now gone over twenty years without either medical treatment or a relapse. Along the way, I picked up and discarded numerous narratives that might help make sense of what happened to me: It was a mystical event, a real encounter with God; it was simply my artistic temperament; it was an accident of timing and chemistry; it was a reaction to a dysfunctional environment, etc., etc. But as such, the book will only work as nonfiction, since it requires some assertion like this really happened to me .

My novels on the face of things look very different: The first is speculative fiction about a portal, the second is this domestic tragedy about sex, and the next one I’m working on is something else altogether. But what they have in common is an interest in the limits of what we know about existence and what happens when we can’t let this question go—a combination of big questions and intense emotionality. One thing I love about writing is how some small craft decision you make ends up affecting the entire feel of the book. For each of my books, this emerges as a difference in tone and style. I know that my style when I write nonfiction is very different from my style when I write fiction, and to me that is less a difference between fiction and nonfiction and more due to the craft choice of having a first-person retrospective narrator whose aim is to try to build a coherent self out of the events that have happened to her.