Don’t Write Alone Interviews

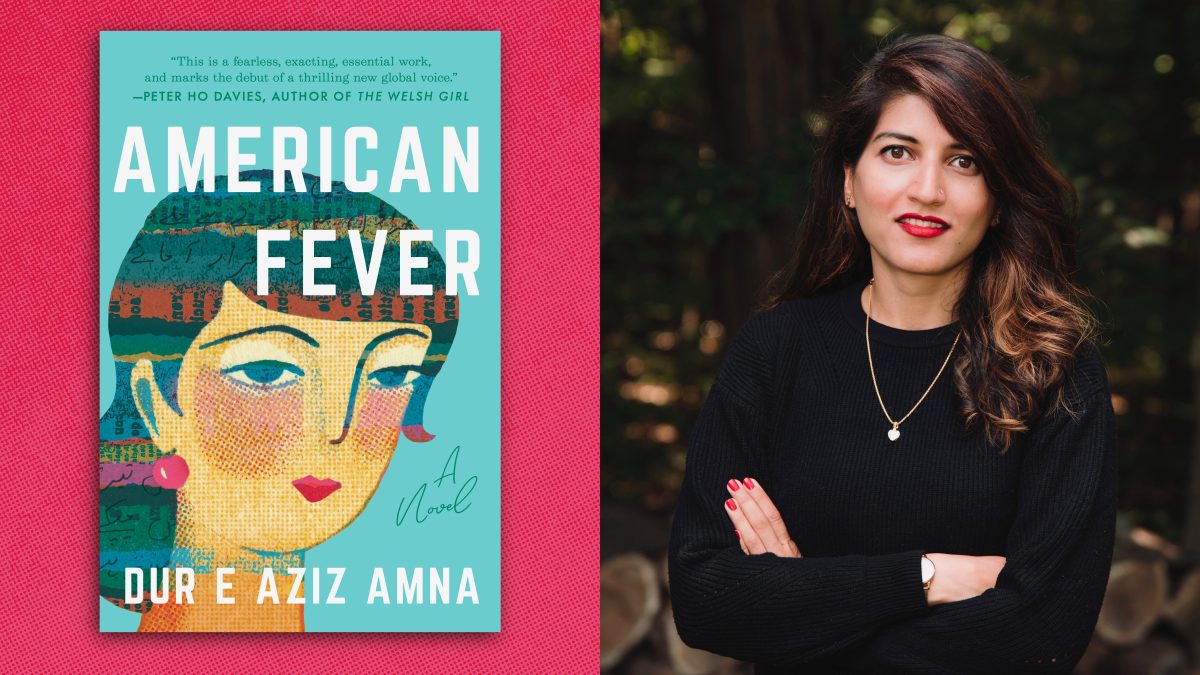

Dur e Aziz Amna Is Adding Something Different to the Canon

Akanksha Singh interviews Dur e Aziz Amna about her novel ‘American Fever,’ the burdens of representation, and performing for the dominant culture.

In the introduction to The Oxford India Anthology of Twelve Modern Indian Poets , Arvind Krishna Mehrotra notes that “we in the subcontinent have been granted a rather unique opportunity: to contribute to the English language in ways that the British, the Americans, and the Australians, and also the Canadians cannot.” To me (an Indian), Pakistani writer Dur e Aziz Amna illustrates the full extent of this lesser-explored English: Throughout her career as an essayist and short story writer, her voice, style, and syntax have remained refreshingly subcontinental and desi.

Her debut novel, American Fever , tells the story of Hira (“hi” like “hit”; “ra” like “Debra”), a Pakistani exchange student in rural Oregon who navigates adolescence, homesickness, and being Muslim in small-town America. Set nearly a decade after 9/11, long before bidets and halal meat became more culturally mainstream, this is almost an anti-immigrant novel. Which is really to say, the witty teen protagonist remains ever critical of the “American dream” and harbors no wish to immigrate.

Over a FaceTime call, we discussed representation, writing for a Global North readership, and the future of the South Asian “immigrant novel.” Our conversation has been edited for clarity.

*

Akanksha Singh: How would you classify American Fever ? I hesitate to call it an “immigrant novel”—would it be fair to call it a coming-of-age novel where the protagonist happens to be “foreign”?

Dur e Aziz Amna: I think I would call it a coming-of-age novel before I’d call it an immigrant novel. As you said, it’s not [an immigrant novel]. To me it’s more a story about a young person coming of age, but because this happens in our very globalized world, she moves from one place to another and is confronted with all these different possibilities and these ways of being and not being.

I would call it a coming-of-age novel before I’d call it an immigrant novel. I do understand the impulse to [categorize] it, and that [label] is a very easy way of explaining it. A lot of the literature about the westward movement is in the genre of “the immigrant novel.”

AS: Would you say that [label] works both ways though?

DA: I mean, you know how there’s books like Graham Greene’s The Quiet American [a book about a white man in Vietnam]? No one would call that an immigrant novel because they’re clearly not there to immigrate. That’s the position Hira’s in; she knows she’s here to observe and go back—and I think there’s very little of that observational novel about the West coming from South Asia. Or I’m sure there are a lot; I [just] haven’t encountered a lot of them.

AS: Neither have I, in all honesty. Which brings me to my next question: This novel and your voice on the whole, is, I think, unapologetically desi. You don’t handhold a foreign reader unfamiliar with certain desi-isms or Urdu words or water down any of it—including some sentence structures I’ve come to recognise as desi. Was this a conscious choice on your part?

DA: I’m glad that you think that it’s unapologetically desi. I think it’s an interesting thing now, that a lot of the time we consider it a sign of authenticity that a writer has food words in a foreign language or one character speaking broken English, and that’s supposed to shake up the linguistic hegemony of English.

It’s interesting what you point out about certain sentence structures [being desi]. I think it’s really cool when that happens! I don’t think it’s very distracting—my goal’s never to alienate people. When we’re writing, our goal is to reach as many people as possible. But I think it’s really cool whenever a writer is able to inflect English, or the other language that they’re writing in, with the rhythms of their own language! It’s sort of like a wink to the people who they share that language with.

AS: Did you find it hard to shop around your manuscript because of this though? Did you ever find yourself self-censoring to be more relatable to a more Global North reader?

DA: To me, what you’re writing about is the most important, and that was also where the friction was. To be honest, this book had a hard time in the American market. It sold easily in the UK, which made sense, with the diaspora there. But I think one of the reasons it took so long to sell here [was relatability]. There were a couple of editors who told me the book should really start when Hira moves to the US. [They said] that the first few chapters in Pakistan are completely extraneous, that’s not where the story is—which is interesting to me because you can’t really tell that story without that context [of being in Pakistan].

I grew up and was born and raised in Pakistan and moved here when I was nineteen. But I wrote a lot while I was growing up in Pakistan, for those news supplements that come with newspapers every week or so. I think a really important thing that did was make me aware, at a very early age, of this audience that existed outside of this imagined Global North audience you speak of. So when I’m talking about class problems in Pakistan, I’m not tackling Pakistan with white readers [in mind]; I’m talking to other Pakistanis.

As we know, it’s the seventy-fifth anniversary [of Indian and Pakistani independence from British rule], [and] there’s been centuries of the presence and domination of English in South Asia, which is terrible in a lot of ways. But what that’s also done is give us a huge English audience in countries in South Asia—that’s who my audience is.

AS: We touched on this in our earlier exchanges, but talk to me about the idea of “performing” for the dominant culture. Often, as BIPOC writers we’re asked to almost prove our “struggles” to get our narratives out. Is this something you were actively avoiding while you wrote?

DA: Yes, I think with some of my initial drafts with Hira, I noticed her observations weren’t ringing true. To go a step back, the novel is somewhat autobiographical; I did an exchange year and was also placed in rural Oregon. The characters that she meets and the host family are completely different, but it is steeped in autobiography, and I remember my experience being both very good and very bad. It’s an experience that changed my life completely by giving me a new perspective, and a lot of things that have happened in my life since have been because of that.

So the first draft came out very didactic and “this is how America is bad for someone coming from abroad.” And I realized that that is not how I experienced it, and that’s not how anyone would experience it. So I almost had to rewrite it, removing this lens of proving how difficult everything is.

One of the biggest things I changed between drafts is that initially the story was told [only] from the perspective of the young Hira. There were certain things that happened to teenage Hira that are not that interesting to an adult reader, unless someone can actually look back at them and contextualize those memories.

AS: Around midway through the novel, chapter 10 opens with a self-aware confession of sorts, about how this could become a “foreigner trying to fit in” narrative. How important was it for you to avoid this?

DA: I think that a lot of literature that we know of is about coming to the West to move here, and there are a lot of great, great books in that canon. And I found myself adding to that canon in my own way, but I also wanted to make sure that I was adding something different to it.

One of the things I latched onto was that Hira was a foreign exchange student. She’s not coming to the US to move here, she’s not coming with family (as a lot of people do), she’s not even coming to college or at a later stage in life. So it’s a very specific moment in her life, where she’s coming of age as a normal teenager with a transcontinental move in the mix. I thought that was one of the ways in which her new perspective could shine through.

AS: Speaking of Hira, was it important to you that she was conventionally likable, being a Muslim teenager?

DA: I think more generally speaking, I’ve heard so much about [likability]. It’s almost become a trope at this point—anytime there’s a young female protagonist in any story, [people say] “she’s not likable enough.”

But it’s actually funny—in some of my earlier drafts, Hira was perhaps more likable. I don’t think she’s mean , but based on some feedback I got from early readers, I wove some of that judgmental [streak] into her in some of the later drafts.

Eventually you realize that the only way to get out of this burden of representation is to [understand] you don’t owe it either culture. AS: How did you balance the honest representation of desi Pakistani communities (both in Pakistan and in the US) and Americans themselves? When Hira broaches her fellow Pakistani exchange student’s choice of wearing a scarf, for instance?

DA: I felt a little hesitant writing that, because of the persecution Muslims, especially post-9/11, have faced in the US and elsewhere in the western world. I don’t want to feed into any of that, but I also know that I have to stay true to the experiences that I’ve had myself. So how do you stay true to [those experiences] while also being aware of larger issues? It’s a fine balance.

We now obviously have so many conversations about representation and the burden of it. If you’re from elsewhere, you experience that first place [where you’re from] in all its complexity, [and] as Hira’s experience has shown, the place that she’s coming from is extremely faulty as well.

And when you’re put in this position of having to either apologize for [that first place] or vaporize it, or completely reject it—that’s what Hira struggles with a lot, and I definitely have as well. You have to condone certain things about home that you yourself have a lot of issues with, and eventually you realize that the only way to get out of this burden of representation is to [understand] you don’t owe it either culture.

AS: Where do you think (or hope) the “immigrant novel”—or, in this case, the anti-immigrant novel—is headed?

DA: I can only really speak to the South Asian diaspora, but my sense is that a lot of the diaspora novels I’ve seen are from people whose families have moved here. That’s obviously a very specific experience, and there’s a lot of reasons for that. There’s the class thing, where a family moves here, and it’s only the second generation that has the ability to write in English, or the freedom to take on a career in writing.

But I think there’s a different perspective when you hear the stories from people who have moved themselves, and they’ve known both the point of departure and the point of arrival. I wish to read more of that.