Don’t Write Alone Toolkit

How to Track If You’re Writing “Enough”

I call my instincts to organize and categorize a project that feels out of control the Religion of Office Supplies.

Whenever I get stuck within a writing project, I focus on an adjacent, concrete task that’s not writing itself, turning to index cards or spreadsheets or page flags. Most recently, I drew the layout of the house my characters live in, needing to know where the doors and windows were, what conversations could conceivably be heard in which rooms. I call these instincts to organize and categorize a project that feels out of control the Religion of Office Supplies. I visit this temple many times during a project.

In December of 2021, the project that felt out of control was my sense of my work itself: its pace and, on a deeper level, my commitment to it. It had been a rough year personally and an unsatisfying one writing-wise. At work on a novel and a story collection, both long projects without tangible wins in sight, I was looking at the prospect of another year that felt the same. I never thought I was working enough. I also knew this was more feeling than fact, a symptom of the writer’s ego and a fuzzy understanding of my own time—how much I had and how I was using it. Could I create a more objective image of what I was doing with my writing days? Could I somehow measure that sense of enough?

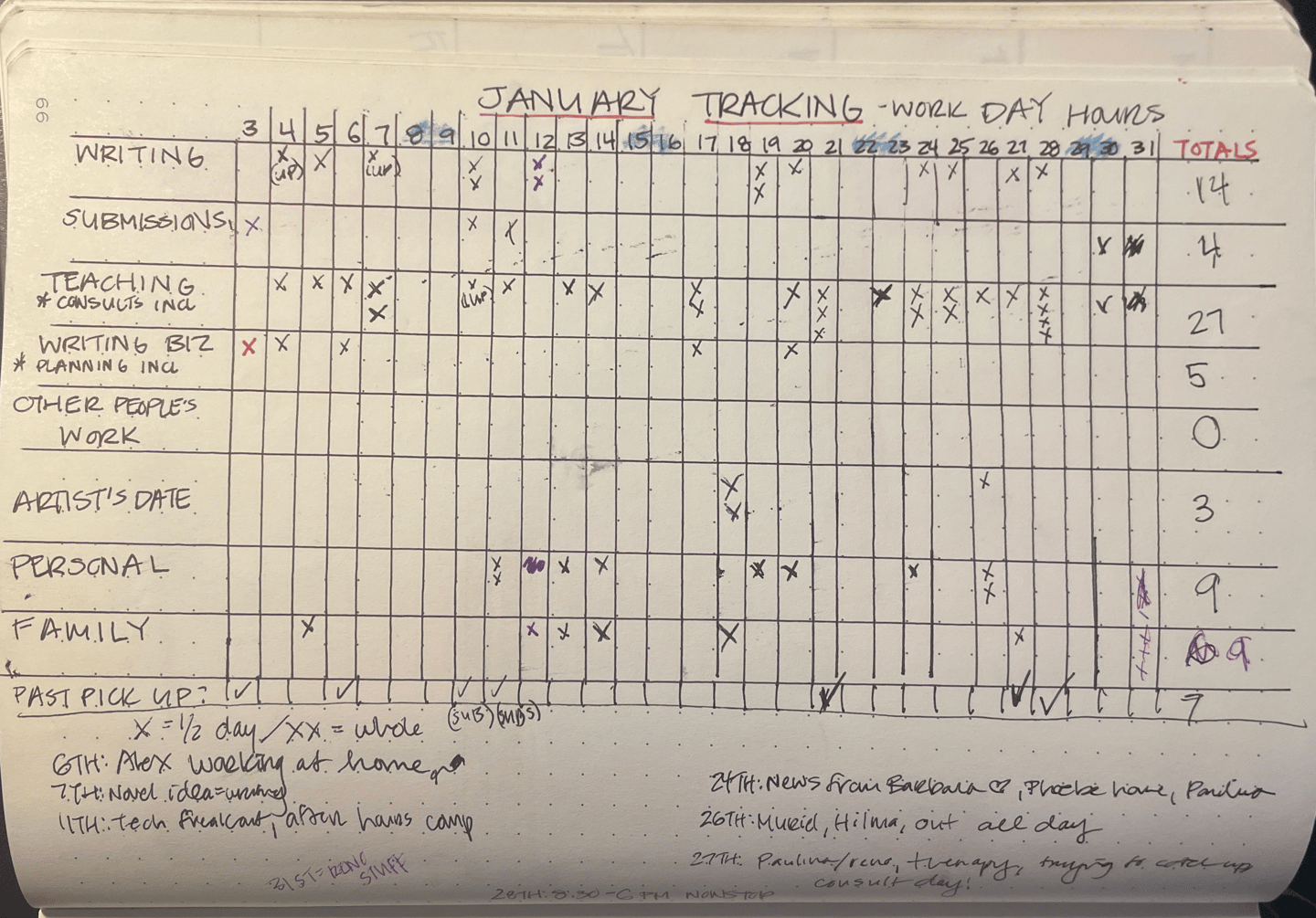

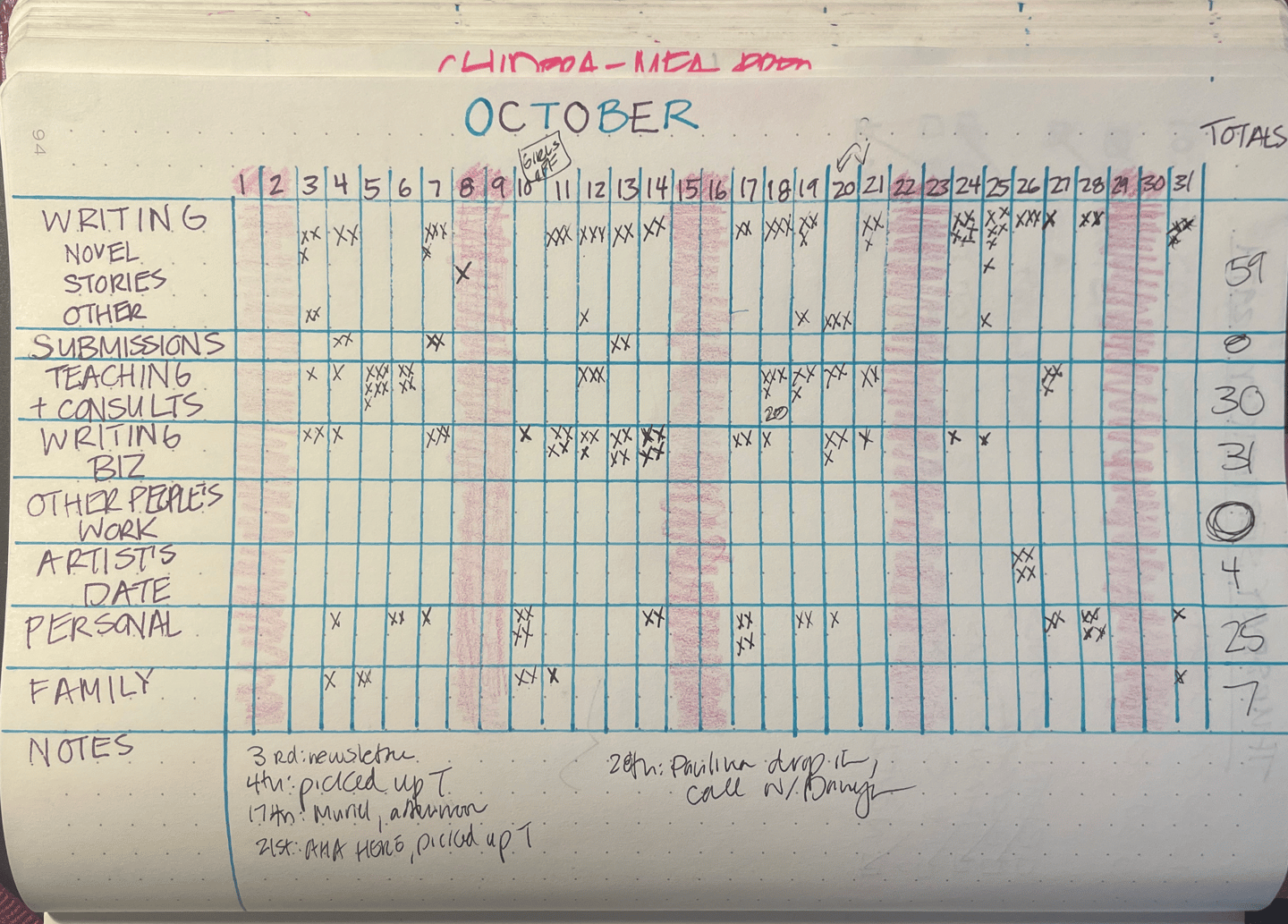

So I began the new year religiously, with my dotted notebook and ruler and fine-point markers, making a grid for the month and assigning categories to ways I typically spent my working hours: Writing, Personal, Other People’s Work, Teaching, and so on. (I definitely did not imagine sharing this with anyone, or putting these images on the internet, so bear with me as you witness the slightly embarrassing inside of my brain.) In previous attempts at tracking, I’d kept precise records of time, but counting minutes had only made me anxious, and so this time, I decided I’d fill my grid with small x ’s, but didn’t assign any value to those x ’s. I’d keep at this for a full year, see if this December felt different than the last.

Every new month as I set up my grid, I was well aware it was a fool’s errand; my past visits to the temple of the Religion of Office Supplies told me I’ll rarely if ever return to the references I make (RIP so many index cards). But also that that was okay. I knew I’d never be readable or quantifiable as a spreadsheet, that I wasn’t a statistician. Yet inevitably, if I followed whatever cockamamie setup I had committed myself to, I always got the information I needed in order to keep moving forward, even if it wasn’t the answer to the question I was asking. The effort always shook something loose, and there was comfort in my attempts to grasp the ungraspable. And really, is it any more pointless to try and measure a sense of enough than it is to spend literal hours (errrrr months, years) inventing people and the universes they inhabit so deeply that whole sections of my brain behave as though they are real? I already operate my business in the land of impressionistic dreamwork, of trusting the asking of the question itself, its inherent curiosity enough.

Photograph courtesy of the author

What was the question I was asking, this time? It was, in some form, the one most nonwriting friends and family ask of writers (hopefully not to their faces): What does she do all day ? For me, that question has always been about more than hours: Am I working hard enough on my writing, am I devoting the right hours to it, am I committed to my art? I’d set my sole goal for the year making my own writing my highest priority on my work list. I believed the tracker would help me see, too, what was getting in the way if I wasn’t writing: my paid projects, my family life, appointments or socializing midweek?

I knew that—though they were relational to minutes or hours—my x ’s wouldn’t mark time proper, but as the months went on it was clear they were impressions of my work, rating-like: three x ’s (I tried!), seven x ’s (this book will be brilliant and done very soon!), one x (very bad, will not return to this establishment!). I came to think of them as measuring energy and engagement, denoting a flow state. Sometimes I felt great about an hour and a half of work and gave it four x ’s, or I spent twice as long on something but gave myself two x ’s if my concentration was easily broken. I expected the x ’s to standardize, but by summer I was looser with them. I was developing a generosity toward myself and my work unhitched from time but still, in its way, countable.

And yet when I plugged this shadily defined unit of measure into a spreadsheet at the end of every month and calculated percentages of how my “time” had been spent, I found it did add up to something. Lo and behold, relationships emerged on those spreadsheets. If I was teaching, I was doing less of my own writing, but if I had freelance gigs or other paid work, my own writing did better than if I only had writing on my calendar, when my creative drive was killed by the stress of not earning income. When I felt restless or unmoored, the daily data showed me that I hadn’t touched my novel in some time; often the length of this stretch away from it surprised me. If I could recalibrate my work distribution, I would. If I couldn’t, at least I knew why I felt out of sorts.

I was developing a generosity toward myself and my work. The month view showed me I was meeting deadlines and making progress on my novel, despite how the day-to-day might feel like neither were true. Past attempts to control my workflow (and life) have been about rigid segmenting, but it seems silly now, the way I feared following instincts rather than plans—pursuing a sudden story idea when I had a deadline, or making a class plan when I had weeks to get it done—would undermine the whole operation. If any time had been wasted, it was probably the time spent telling myself I was working on the wrong thing when it all came out in the wash.

Boundaries blurred on my definitions of working time too. I found myself slipping into the most inane of questions about what was worth counting: the notes thumb-typed into my phone on the subway on a weekend afternoon? What about reading? Was working on my newsletter considered writing or writing business? Was a conversation with a writer friend where we came around to discussing work “working”? Did it matter? Ultimately, I decided my questions were inane, but the conclusions I came to were not: We can’t just stick our writing selves and our personal selves into time slots. I make efforts to have off-hours—notably I rarely work weekends, though I could now clearly see both the stretch of them as available to me and my choice not to use them—but I am always on, the writer self always reachable for a quick set of notes or curiosity piqued.

Photograph courtesy of the author

The other selves I am—parent, daughter, person with a body that needs its own attention and care—were also always reachable. Seeing all my x ’s helped me better understand the relationship between what I could control and what I couldn’t: emergency dental work, a paid project that took more time than expected, managing a family matter. I can make lines between the parts of my life on the grid all I want, but I cannot truly compartmentalize my writing self and my income-earning self and the self that’s there for myself and others. What gets in the way of what, and is anything, really, actually in the way? Or have I just been raised in a culture that believes my days should be single-mindedly purposeful, neatly slotted into hours, minutes, silly little x ’s?

Paradoxically, the way I let go of that idea was to organize data points that showed me my brain worked best when it allowed its various selves to bleed into one another in life and in time. By midyear, I took more days to focus exclusively on family or personal things—what I had formerly seen as distractions or rewards—on days I had not wanted to give up to anything but work in the past. As the months wore on, it was clear there wasn’t a problem to be found in my grids, unless you count living as a problem.

If you’re here because you want a shortcut to feeling in control, or a lamppost, or any shred of guidance, I wish I had an airtight solution to offer you, as I’ve wished before to have one offered to me. Getting through a year of my little x ’s made it obvious they were both pointless and essential. More than anything else, they were a conversation with myself about that very desire to mark and account for my time and work, the most elusive part of the writing life. As an act of witnessing, this tracker is the single best thing I have done for my process in a long time. Little x by little x , I witnessed my days—building a time lapse of both my work and the life it lives inside—and that was enough to keep feeding my efforts on my projects, to dig me in deeper on the process of writing, which can be all we have when a milestone isn’t in sight.

My tracker laid bare all that I was doing daily, personally and professionally, all the levers I could or would not pull, the interceptions of my life I could not circumnavigate. I saw I could not be all my selves at once—each of which are, if not desirable, then necessary in some way—while also finishing a book as quickly as I want to. I’m still uneasy with my pace, but I’m closer to making peace with it. This December, I’m no longer questioning if I’m trying hard enough, if I’m properly devoted to my life’s work within the confines of my chosen work, even when I don’t have anything to show anyone yet beyond twelve grids full of small x ’s.

I do think my method is both a practical tool and a vital line of questioning for anyone who struggles with notions of commitment and progress in regards to their writing. I do think you should try it if it feels like you might have a question about how you spend your time. What happens when you pull back on the sum of your days, weeks, months? What can you measure beyond your hours or words? What can you see building in your work, even if—especially when—it feels like you cannot grasp that progress at the moment? What will your little x be a measurement of? You won’t likely know at the start, it most likely won’t be the same as mine, and that’s okay. The answer to that question is where the meaning lies.

You might also discover a shift you want to make, that in months when you take on more, your creative work thrives, or that some month is always a wash because of family or work obligations, or that you’re putting more unpaid time into other people’s manuscripts than your own. You might surrender to those observations, or you might see what can be shifted. Whatever you discover, it will have been there all along, but you’ll be able to make clear-eyed choices now that you’ve made it impossible to ignore.

I say track whatever, however, if it gets you through the days required to finish the project you are moving through, if it can help you forget—or see with more compassion—how long it’s taking. Me, I set up some false god from the Religion of Office Supplies— x ’s, percentages, color-coded whatever—to guide me to the place I can see myself most clearly, most kindly. I don’t have a religious practice, but the best ones seem like this: the act of looking at your time and efforts spent, your devotion, and asking, Is it enough? After all, the call that tells us to go faster, harder, better, is usually coming from inside the house. In witnessing our process, we claim it. We become our most reliable support systems, nudging and forgiving and proud. I’ll never work fast enough for myself, but some days I will please myself, be deeply satisfied by something other than numbers or photos of stacks of pages I can post on social media. Like so much else in my life, it helps to mark that sort of day by writing it down.