Don’t Write Alone Toolkit

How to Set Yourself Up for Success at Your Writing Residency

This guide is meant for writers who are dreaming of getting away to write—and addresses the anxiety many of us feel when we finally get that treasured chunk of time.

The first time I entered my writing studio at the first residency I attended, I felt two things simultaneously: glee and panic. I had two whole weeks away from teaching, from my family, from meal planning, even, to do nothing but write. I’d been looking forward to it for months. But once I arrived, I was a little overwhelmed by the expanse of open time ahead of me.

In the years since then, I’ve attended many more residencies, including formal residencies—with meals provided and other artists and writers to commiserate with across the dinner table—and self-made residencies where it’s just me and a premade chicken pot pie at a tiny Airbnb. (It isn’t the venue that makes the magic.) A couple more notes about how to decide where to go: Maria Robinson’s “Get Thee to a Writing Residency” provides this useful list of questions to help you decide if the residency you’re considering is a good fit for you, the Artist Community Alliance has a comprehensive directory of residencies , and the Sustainable Arts Foundation has a list of parent-friendly residencies .

This amiable guide is meant for writers who are dreaming of getting away to write—and addresses the anxiety many of us feel when we finally get that treasured chunk of time: Now that I’ve got all this time, how can I make the most of it?

First, a word about what I mean by “residency”: yes, fancy places like Yaddo and MacDowell are amazing. I, too, dream of hiding away in a cabin and having my lunch brought to me in a little picnic basket. But those places are hard to get into and can be inaccessible in all kinds of ways—they’re deep in the woods, which isn’t for everyone; they typically require you to stay for at least two weeks, which is more time than many people with day jobs, kids, or other caregiving responsibilities can manage. If a formal, far-away, long-term residency won’t work for you, you can use just about all of these ideas to make your own residency, whether that’s a weekend in a rustic cabin or a Sunday afternoon in a coffee shop. Novelist Lydia Kiesling wrote most of her second novel in a series of self-made retreats in cabins with composting toilets . Essayist Emily Maloney is working on her second book at a friend’s desk she’s borrowed for a couple weeks at a time. Writer Paulette Perhach recently wrote a great piece about pet sitting as a secret to cheap travel , so if you don’t mind dog walking during your stay, you could pet sit your way into a writing residency and earn a little money along the way. And you don’t have to go far or go alone: novelist Erin Flanagan has borrowed her sister’s house for group retreats in the town where she lives. She described the benefits of this near-home residency: “It’s local, but like a separate world so we all feel like we’re escaping the pets/children/ailing parents/flotsam of our lives but are still close enough we can be home in minutes if there’s an emergency.”

You don’t need a fancy studio to get your work done, and you don’t need to wait for someone else to make the space for you. Call yourself the writer in residence of Panera, if you like. Your residency is where you make it.

So now that you’ve got some dedicated writing time marked on your calendar, how can you maximize it?

Allow some time to ease in: No matter how ambitious your hopes for your residency, it’s a good idea to give yourself a moment to ease in to the new space. Unpack, read a book, take a walk. Maybe start making a list of what you’d like to work on during your time. You don’t need to be off to the races the moment you arrive. I think of this as dreaming my way into the residency.

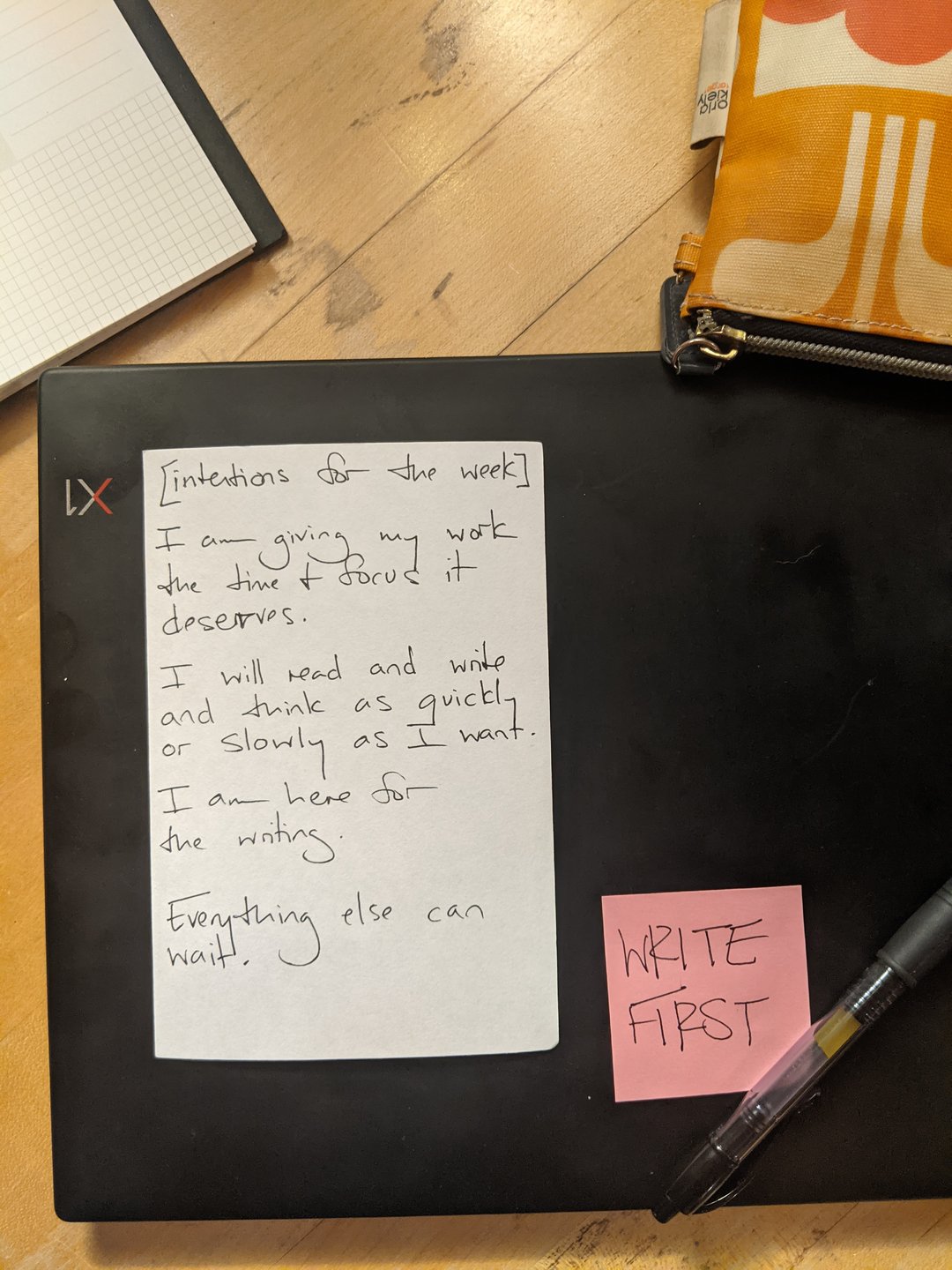

Set intentions and define your goals: At a residency, there’s an important balance between having high hopes for what you’ll do without putting too much pressure on yourself. Before setting goals, I like to define intentions for how I’ll work: checking email only once per day, for example, or using a browser extension to block distracting websites. For my most recent residency, a week in a cozy cabin at the Barn at Boyds Mills , I wrote my intentions in Sharpie on an index card and kept it on my desk front and center the whole time. It felt a little hokey, but it kept me centered and reminded me why I’d taken that time away from my regular life and family.

Photograph courtesy of the author

One way to approach your residency is to think about what you can do in an extended period of time that you can’t do in your regular life. If you’re writing a book of poems, for example, you can chip away at the drafting and revision of individual poems in smaller chunks of time (I drafted many of the poems in my most recent book in moments stolen before day care pickup), but if you’re thinking about shaping those poems in a cohesive manuscript, that’s work that benefits from the extended time and focus of a residency. (Not to mention a big blank wall so you can tape everything up. I always take painter’s tape with me!)

In addition to considering how you want to work, it’s also helpful to set some boundaries for what you don’t want to let in. You don’t need to cut yourself off entirely from the outside world while you’re away—by all means, call your partner or FaceTime your kids, if that’s going to make being away from home better! Hannah Bae’s excellent “A Person of Color’s Guide to Navigating Writing Residencies” makes a powerful argument for selecting a retreat near friends and family as a way of building community and security while you’re away from home. However, you should consider if there are distractions you want to eliminate while you’re away. I like to take a couple of cozy residency pictures and post them to Instagram with a little note about what I’m working on for the week, then delete the app from my phone and savor the extra brain space I’ve acquired by not knowing what anyone else is eating for lunch or wearing to work.

Once you’ve defined your intentions for your time, consider what you’re working on. Some writers schedule a residency when they have a firm deadline for a project, like nonfiction writer Erika Bolstad, who used three- and four-week residencies to write big chunks of her forthcoming book Windfall . But your goals might be more flexible, and you don’t have to produce thousands of words for your time to be valuable. When I was at Boyds Mills, I met young adult writer Alex Villasante , who was using a long weekend to reflect and brainstorm projects for the year ahead. (She shared three questions she was using to reflect, as well a generative prompt her agent had given her.) Even Bolstad, who wrote thousands of words at each of her residencies, noted that she aspires to have her next residency be less focused on a deadline and “more chill and generative.”

Once I’ve set intentions for how I want to work, I consider the what . I make a list of all the projects I might work on, and I categorize them (this can include drafting as well as revisions, editing, reading, and research) and figure out which ones are of the highest priority. When I’m thinking about what I’ll work on, I like to set three tiers of goals: my absolute biggest dream of what I’ll accomplish; a kind of middle, more realistic goal; and the essential things I have to do—like, can’t leave until they’re done.

If you’re retreating with friends, as Erin Flanagan does, sharing your goals for the time creates an additional layer of accountability.

Establish a rhythm for your residency: One lie I’ve often told myself about my writing life is that if I can make a perfect list or a better schedule, I’ll be able to really amp up my productivity. And while I think there’s value in structure and planning, I’ve also come to appreciate flexibility in a writing routine. At your residency, you might think of rhythm rather than schedule. A schedule feels like punching in to a nine-to-five; a rhythm captures the goal of making space for your creative flow.

So for your rhythm, consider what kinds of tasks you want to work on and which times of day work best for that work. I’m always sharpest in the morning, so I do my new writing first and save reading, editing, research, and other tasks for after lunch. You might find that you like to wake up with a walk and ease slowly into the day, or that your brain really gets going late at night. Whatever rhythm suits you best, I think it’s helpful to have a general outline of what you’ll work on when. I like to make a list, each night, of what I’ll start with the next day. It’s not rigid and it’s not overly ambitious, but it’s enough that I know where to begin. A certain level of planning can help free up the creative part of your brain to do its work.

Several of the writers I talked to described a rhythm that began with a very early morning. Erika Bolstad talked about her rhythm during the three weeks she spent at Playa in south-central Oregon: “I got up every morning with the sun, which was at 5 a.m. in June. I ate a quick breakfast and made a giant pot of coffee and did morning pages, and then wrote for three hours. Then I exercised. After that, I worked until I got hungry, then made myself lunch and more coffee and worked all afternoon, often into the early evening.”

However, there’s no particular virtue to getting up early—so if that’s not your thing, don’t worry about it. One of the joys of having so much available time is that you can work with whatever your natural rhythm is—or work in ways that don’t always align with your schedule at home. I remember, several years ago, when I was at the Vermont Studio Center, heading back to the studio after an evening program because the artist talk had helped get my brain unstuck. It felt almost illicit to be working in the part of the evening that at home was always consumed with my kids’ bedtime, but that flexibility is one of the gifts of a residency.

Closing it out: Before you head home, take a little time at the end of your residency to capture the highlights of what you’ve worked on, as well as make plans for what you’ll do next. Two quick lists will work, and you’ll probably be really impressed by how much you’ve accomplished and the good ideas you have going forward. That way, your residency isn’t just time away, but a chance to launch yourself into something new.