Don’t Write Alone Shop Talk

How Do You Publish a Book In Translation?

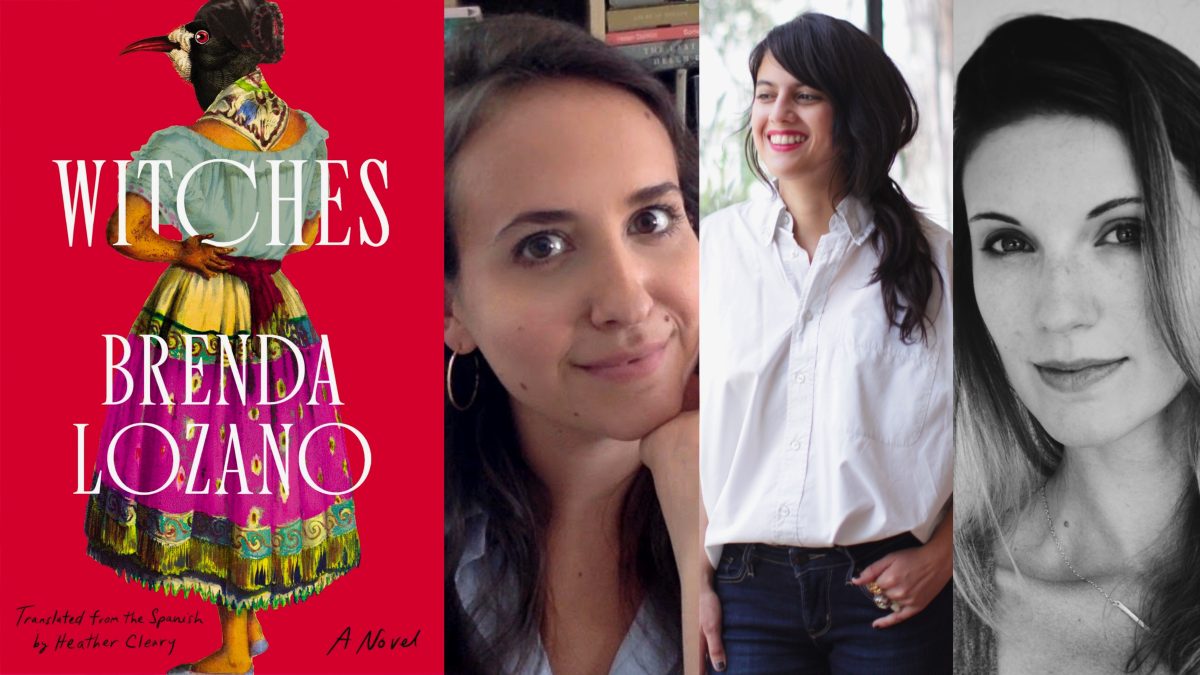

A roundtable discussion with Brenda Lozano, Kendall Storey, and Heather Cleary on why translation is essential to the literary landscape.

Catapult Books has a robust list of works in translation. One of our 2022 titles, Witches , tells the story of a young journalist, Zoe, who is reporting on a murder in San Felipe, Mexico. Her investigation brings her into the company of a legendary healer, a curandera named Feliciana, and the women’s lives and stories begin to intertwine.

As part of our translation-themed series, What’s the Word Witches —Brenda Lozano, the novel’s author; Kendall Storey, its editor (and the editor-in-chief of Catapult Books); and Heather Cleary, who translated the book from Spanish into English. In this conversation, they discuss the nature of their collaboration, their theories of translation, and the importance of translated works to the literary landscape.

Brenda Lozano ’s responses have been translated by Vanessa Genao.

*

To start, I’d love if each of you could speak to your role in the process of bringing Witches to publication, and how you collaborated with one another in translating the project into English.

Brenda Lozano: The first thing I wrote was the voice of Feliciana, the curandera, who was a secondary character in a novel I never finished about the birth of a volcano in Mexico in the 1940s (which is a story I find fascinating). I tried to finish it several times, but in Christmas of 2016 I copied a paragraph I liked from that failed novel, and on a trip to the beach, in a notebook I bought at a Walmart and with a pen with the hotel logo, I developed what I liked about the voice of that secondary character into Feliciana. During that Christmas I wrote maybe sixty to eighty pages (which is a lot for me!) about parts of this character I was interested in developing. I wrote the whole novel between 2017 and 2019. I really enjoyed those years; I remember them fondly. Being with that manuscript meant an immense freedom and many hours when I felt very happy.

Editing a manuscript in translation is quite different from editing one written originally in English. Heather Cleary: I translated the book, which involved talking with Brenda to lay a few foundations at the outset and then working with her again toward the end of the process to clear up any questions and think through a few possible adjustments to help the novel breathe in this new atmosphere. And then I worked with Kendall to give the manuscript a final polish and get the translator’s note together. I was very grateful for the space to reflect on some of the decisions behind the way the novel ultimately appears in English, and to discuss certain cultural and historical elements of the story that might not be immediately evident to readers here.

Kendall Storey: Editing a manuscript in translation is quite different from editing one written originally in English. Since the book has already been published in its language of origin, I don’t make any suggestions about plot, structure, character, etc. Instead, my responsibility is to make sure that the translation reads fluidly and naturally in English—that each sentence is rendered into an English that is alive and captures the spirit of the original.

But an editor’s job is not done when the manuscript is edited! I remain involved from acquisition through the publicity and marketing stages, and truly for the entire life of the book. I help to secure blurbs, pitch the book to reviewer and bookseller friends, collaborate about events and tour details, and generally champion the author and translator at every stage. It’s a wonderfully intimate process and I’m so grateful for the relationships that are formed and nurtured along the way.

Kendall, how did the manuscript originally come across your desk—can you walk us through the process of acquiring a manuscript in translation and selecting a translator?

KS: In this particular case, Brujas was represented by Agencia Carmen Balcells. I’d heard wonderful things about the novel from a couple of trusted readers, and so I asked the agent to share it with me and quickly put in an offer. There was an auction for the US rights and luckily, we prevailed!

The UK editor and I decided that we would invite a handful of excellent literary translators to submit sample translations of the novel which we would then read “blind” before selecting our favorite and offering its author the contract for the full translation. Heather’s sample stood out for its aliveness, fluidity, and for the incredibly thoughtful choices she made throughout (e.g. leaving certain words in Spanish, a choice she explains brilliantly in her translator’s note). We were thrilled when Heather accepted the job!

But this is just one example of how a book comes to be published in English translation at Catapult and elsewhere. We receive submissions from agents, foreign publishers, and literary translators. Sometimes I’ll contract directly with a foreign publisher when there is no agent involved, and I love receiving pitches directly from translators. They are almost always the deepest and most sensitive readers of the books they translate, and it’s such a joy to work together refining each and every sentence.

Brenda, had you thought about publishing your novel in translation during the process of writing it? Was it something you sought out?

BL: That’s a good question. I didn’t think about translating it to other languages, but in a way, the writing was a thought exercise in ideas around translation. Zoe speaks Spanish, she writes her part in first person and transcribes Feliciana’s part with the help of a translator. Feliciana speaks in an indigenous language, maybe Mazatec; she doesn’t speak in any hegemonic language linked to capitalism and the State, the way Spanish and English are. And this aspect was very important to me when imagining the novel: the references, the metaphors, the repetitions, the mode of self-expression was to make it look more like a clear night filled with stars, rather than an afternoon of traffic in a city. Language is also political, how we speak is political, and Feliciana is one form of resistance after another. She’s a woman from an indigenous community, she’s a curandera on the margins of the medical system, she’s a widow who raised her children alone, and she’s very proud of that as her present. Zoe accesses what she says through a translator, Zoe writes and transcribes and that is novel we read, so there was a fun game of thinking of what she wrote as a game of “telephone,” the translation of an imagined translation.

Heather, how did you approach the translation for Witches? How did it differ, if at all, from other translations you’d done before?

HC: In a practical sense, my approach to Witches was actually informed by another polyvocal novel I translated recently—Betina González’s American Delirium . I’d developed a system for that project that worked very well here: I translated the first draft straight through from start to finish, then broke the novel down by voice and edited each of those separately before reassembling the whole thing and giving it a final pass for flow. In terms of the content, this was the first novel I’ve worked on in which a character was based on a person who had actually lived, breathed, and been filmed speaking; just as Brenda drew inspiration from the life of the curandera María Sabina, I looked to footage of her to model certain aspects of Feliciana’s voice, particularly in tone and rhythm. There’s a bit more on this in my translator’s note.

What was the collaboration like between writer, translator, and editor?

HC: It couldn’t have been a more luminous experience. Brenda is such a joy to work with and the entire editorial process was a dream. As were the conversations around the book’s design and publicity . . . you all are amazing over there.

BL: One of the things I am most grateful for in this collaboration is having met Kendall and everyone at Catapult. The whole process has been wonderful and I hope that this is the beginning of a longer relationship with Kendall because I think her work is incredible. Heather Cleary, first and foremost, is my friend. And this book in English is very special to me because it’s the result of a friendship: conversations, voice memos in WhatsApp, stickers, a lot of questions and laughter, too. For me, friendship comes before everything else, and, of course, way before any book, and in this case, I had the enormous good fortune to have done it with Heather, who, besides caring about, I admire a lot. She’s brilliant, she has a big heart, and professionally is outstanding. So this collaboration with Kendall and Heather is a gift to me.

I’m obviously biased, but I think translation is the lifeblood of literature. What are each of your thoughts on the role of translation in the literary landscape?

HC: I’m obviously biased, but I think translation is the lifeblood of literature. Translation allows readers and writers to come into contact with modes of storytelling, approaches to style and form, and narrated experiences that might not have existed before in their literary ecosystem. That’s an incredible thing in its own right, but it can also have a ripple effect, opening up a sense of possibility for works written after.

KS: As many know, only three percent of the books that are published each year in the US are translated. Publishing literature from other countries is not only crucial to exchanging ideas across cultures but also to maintaining a vibrant American literary landscape.

BL: I have a friend who says that literature is the history of bad translations, and I like that idea. I think incredible things often happen in those bad translations. I think that often in those errors, in the impossibility of translating something, we run into the uncertainty of life itself, where detours often take us to better places than the plans we make. That lack of control, that impossibility is very powerful, very interesting to me. Those errors are literature, too. And from there, how we retell our literature through different versions of the same story or versions of our own life—because if we’re lucky that’s filled with errors of translation, too.