Don’t Write Alone Interviews

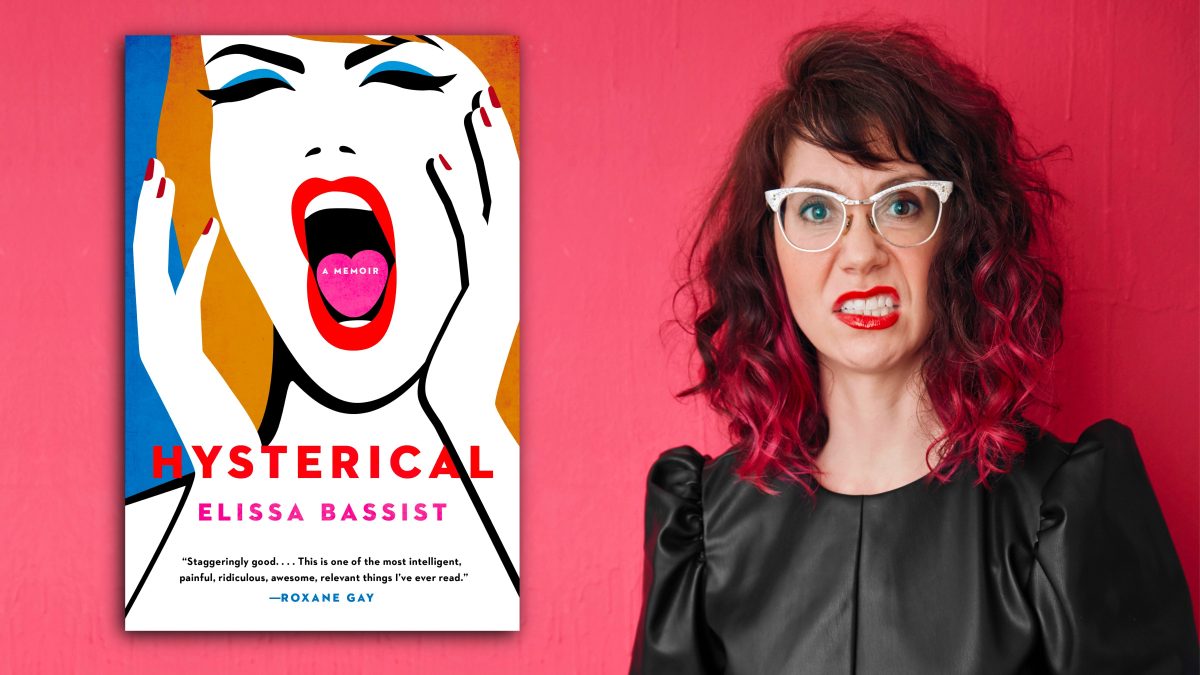

Elissa Bassist Gave Her Book Everything She Had

In this interview, Elissa Bassist discusses her memoir “Hysterical,” keeping her humor sharp, and the endurance test of writing a book.

In elementary school, I was too embarrassed to ask to use the restroom. Speaking up in front of the boys in class was mortifying. Eventually, the internalized hatred and shame of my own body resulted in chronic UTIs. This attitude toward my own needs is widespread among female-identifying people, and it’s a dynamic that Elissa Bassist explores in her memoir Hysterical . Before reading her book, I hadn’t found much literature (especially witty literature) on how misogyny shows up in the body. What a relief to find a book that articulates so many frustrating and familiar experiences; I couldn’t put my highlighter down.

Described as part “medical mystery, cultural criticism, and rallying cry,” Hysterical is about “how a woman’s voice develops (or doesn’t) in a culture where men talk and women shut up.” In her own life, the expectation of this silence made Bassist sick. Her various illnesses led to endless doctors and alternative specialists who couldn’t figure out the root cause. Finally, one of them suggested she might be experiencing repressed rage and recommended a talking cure.

Hysterical examines who gets to speak and why, society’s fascination with dead girls, the “rape-culture iceberg,” and how to reclaim your voice. Bassist and I emailed over the summer about sexism in its myriad forms, the endurance of writing a book for eleven years, and the best decision of her career. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

*

Christina Berke: The medical mystery woven through Hysterical reads almost like a feminist detective thriller. Along the way, we learn upsetting facts about the medical industry that routinely risks women’s health: 70 percent of patients with medically unexplained symptoms are women; depression is more prevalent in women; most medications aren’t tested on women or on mensturating bodies; many doctors aren’t taught about menopause. How did you write about this without losing your mind?

Elissa Bassist: A few weeks before my book deal, I adopted a busted Yorkshire Terrier who was rescued from a dog-sex-trafficking ring (backyard breeding), and when writing the book, every time I dropped to the floor to have a panic attack, he’d jump on my back or bring me his toys, so I wasn’t able to lose my mind at all. Also, he wasn’t housebroken, so I was more worried about his potty schedule than my mental state. Adopting a dog was the smartest decision of my life and career.

I did have one breakdown when he was sleeping while I watched Promising Young Woman . I needed it. I’d worried I’d desensitized myself to the topics I wrote about by writing about them so much, and I want to break down every time I face a woman in pain. I don’t want societal indifference to women to become my own. I hate that I can’t remember the names of every woman who accused former president [BLEEP] of sexual harassment, sexual assault, or rape—the women whose experiences should induce a collective rage that rips a new hole in the ozone.

CB: The majority of your sources and quotes come from women and people of color. Was this a deliberate effort to give voice to those who are typically left out of the narrative? Was it more challenging to find non-cis, non-white, and non-heteronormative sources?

EB: Yes and yes. For an earlier version of the book, I had a note on research titled “Ladies Is Pimps Too,” where I proposed one place on earth in which cis white men didn’t have a say. This wasn’t to exclude or silence men, or to commit “editorial castration”—or even to highlight that often only white men are quoted, cited, referenced, and have spoken on any and every topic since the beginning of time and will be echoed until the end of it. I wanted to collect [the voices of] women and BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ [people] and walk the walk [while] talking the talk.

The number of women in any given field is small because we don’t have the same social and economic capital as white cis men. To pull it off, I had to cut a lot of what I’d written. I’d spent years including research and words from men I then spent more years trying to delete. (So much editing is necessary in revolutions.) Doing so, I realized how often I quoted men, how often I feared that my own voice and opinion [weren’t] good enough.

There were other obvious roadblocks to this political act, like there was no “lady Aristotle.” And the number of women in any given field is small because we don’t have the same platform, visibility, respectability, access, credibility, funding, and social and economic capital as white cis men, which they have taken or inherited and continue to gift to those who look, act, talk, think, and do sports like them. So I rephrased men in my own way or quoted Susan Sontag quoting Aristotle or researched harder to find a woman on the same research team as the man I had credited automatically. Though it was difficult to find scientists who are women, it was worth the effort, because they are there.

Ultimately, my experiment failed—there was no way to write without men’s voices, not like the infinite ways to do literally anything without women’s voices.

CB: Hysterical is very funny, and in just the right places, like turning the standard medical questionnaire into jokes: “Do you sleep too much or too little? Are you exhausted from giving your all, yourself completely, to the men of the world?” You also teach comedy writing and edit the Funny Women column for The Rumpus , which must have informed the balance of humor and tragedy throughout the book. What keeps your humor writing sharp?

EB: The simple answer is “writing across genres.” My sad nonfiction writing deepens my humor and makes it more vulnerable; my humor writing lightens my nonfiction and makes it more fun (to write and to read). Many of my students want one writing identity, to commit to fiction or essays or scriptwriting. But why not have it all? Plus, in trying everything, you can learn what you don’t like and never try it again, which was my experience with novels.

CB: What techniques helped you the most when writing Hysterical ?

EB: My number one technique is Post-it Notes everywhere with quotations like, “Protect your time. Feed your inner life. Avoid too much noise. Read good books; have good sentences in your ears. Be by yourself as often as you can. Walk. Take the phone off the hook. Work regular hours.” —Poet Jane Kenyon

But because willpower is a myth, I use blocker apps like Freedom, which disables the internet, and Freedom 2, which disables internet on the phone, and Self-Control, which blocks distracting websites. If podcasts have taught me anything, it’s that the way to break a bad habit is by making it inconvenient, so I’ll keep my phone in another room or locked in my mailbox in my apartment’s lobby (I live in a fifth-floor walk-up). Before the pandemic, I went to cafés without internet or didn’t ask for the Wi-Fi password, or I wouldn’t bring my charger to artificially impose the terror of time running out. And I use meditation apps to increase my focus and decrease my anxiety (my favorite is Oprah and Deepak Chopra’s 21-Day Meditation Experience), but so far I haven’t seen results.

My sad nonfiction writing deepens my humor and makes it more vulnerable; my humor writing lightens my nonfiction and makes it more fun. I had to forget about “romantic ways” to write, e.g. in a cabin by a lake. I abide by the Pomodoro Method (I break up my work day into twenty-five-minute, single-task increments, like “write bad paragraph,” “revise bad paragraph,” “write a love note,” “revise love note”; then I set a timer, write without distraction, stop when the timer dings, and take a five-minute break). Now my dog is on the Pomodoro Method and wakes up from twenty-five-minute naps to play for five-minute breaks.

Another technique is to expect less rather than more of yourself. My brand of writing is Lowered Expectations, named after the MADtv sketch . I aim for “five Pomodoros today” rather than “write all day” because I must trick myself to work, and if I have all day to write, then I’ll do anything but write. There should be a cleaning service run by writers on deadline.

CB: How did you balance research, memoir, and criticism?

EB: Because I write memoir, I don’t want to be accused of navel-gazing, so I research, but I hate that I have to preemptively defend myself against navel-gazing, so I add criticism of the forces that make me feel defensive.

CB: In the chapter “STFU,” you write about being in an MFA program and getting harmful feedback. What do you think are the pros and cons of writing programs?

EB: Pros include accountability and deadlines (writing is never “done”; it is only “due”); reading and writing as a lifestyle; exposure to new books, stories, essays, etc.; community (potentially); [the fact that they] will help you if you have a high-self-esteem problem.

Cons include but aren’t limited to classroom trolls (potentially); [the fact that they are] expensive (potentially; please don’t go into debt for your MFA because it won’t pay you back—instead apply to funded programs or marry rich); [the fact that] a lot depends on teachers and other students; [the fact that] people write about oral sex but don’t perform it.

CB: Many writers are also teachers, and I remember a writer once cringing when a male student quoted her writing about her clitoris. You’ve taught at places like The New School, Catapult, Lighthouse Writers Workshop, and 92NY. Any awkward and uncomfortable moments with your students regarding your writing, or does teaching censor your writing at all?

EB: No awkward or uncomfortable moments with students whatsoever. Does this mean that my students aren’t reading my writing? And why aren’t my students quoting my writing? Why aren’t my students more interested in my clitoris? Do my students not love me, as I assumed they do? But if my students did read and quote my writing (again, why are they not doing this?), I wouldn’t censor a word or body part. Like most memoirists, my worry revolves around my family reading about and quoting my clitoris (which is why I believe you must write as if your family is illiterate).

CB: Cheryl Strayed told you to “write like a motherfucker.” What specific advice did she give you on writing Hysterical ?

EB: So when I was twenty-six, I knew I wanted to write a book, and not to be dramatic, but at twenty-six I felt like I’d die if I didn’t. At twenty-six I expected I should be able to do it, and it was only a question of talent, inspiration, of waiting on the miraculous, and of being a man (because men’s writing is “writing” and women’s writing is “women’s writing”). At the same time, I barely wrote, and I had an envy mindset, and I had a lot of shitty beliefs, like that wanting to die for one’s art was the meaning of life.

Rather than seek immediate medical attention or therapy, I wrote a letter to the online advice columnist Sugar (who later revealed she was best-selling author Cheryl Strayed). In her response, she confided that her mother died when she was young and the only way she could live and live without her was to write a book. But at twenty-nine she hadn’t done it, which was a “sad shock” to her because she’d “expected greater things” of herself. Same. Then, years later, she “finally reached a point where the prospect of not writing a book was more awful than the one of writing a book that sucked,” so she “got to serious work on the book” and didn’t care “if people would think my book was good or bad or horrible or beautiful” because she’d “given it everything I had.” Which she was able to do because she “let go of all the grandiose ideas” she’d once had—“So talented! So young!”—and “stopped being grandiose.”

Her final piece of advice was to suffer, of which depressives like me have perfected the art—but she meant work and work hard, surrender and rise to mediocrity, go above my Nerve like Emily Dickinson, and write “Not like a girl. Not like a boy. Write like a motherfucker.”

Once I stopped being grandiose, once my goal was to write a book that sucked, once I heard about the Pomodoro Method, once I gave up imagining reviews and what people would think, once I gave it everything I had and sat in a chair for ten thousand hours and wrote, at some point I was in my early late thirties and had a book to revise.