Don’t Write Alone Interviews

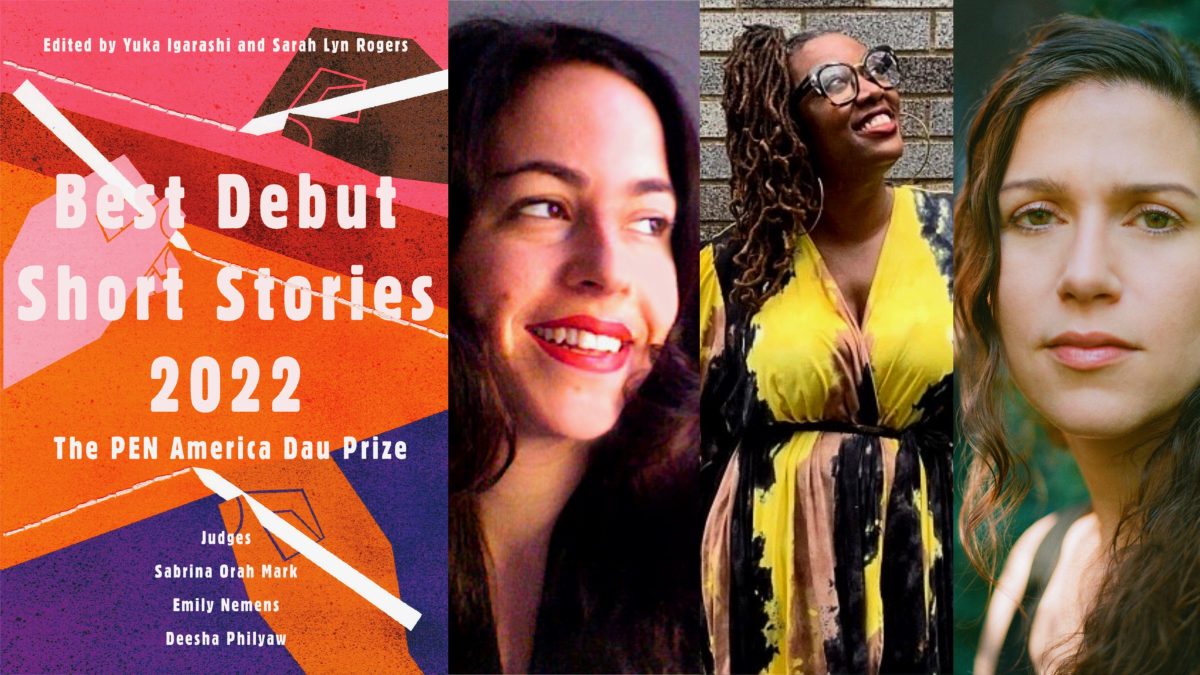

A Roundtable With the PEN America Best Debut Short Stories Judges: Sabrina Orah Mark, Emily Nemens, and Deesha Philyaw

Many of the stories felt written on the edge of an edge of an edge of a world.

Each year, PEN America and the Dau Foundation award twelve writers the PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers for the best debut stories published the previous year in literary journals. Winners are selected by a trio of judges known for their work in short fiction, and are published in an annual anthology by Catapult, with an intro by series co-editors Yuka Igarashi and Sarah Lyn Rogers.

We talked with this year’s judges—Sabrina Orah Mark, Emily Nemens, and Deesha Philyaw—about the selection process, surprises in the work, their first publications, and advice for early career writers.

*

Catapult: Were there particular things you were looking for as you read the nominated stories?

Sabrina Orah Mark: I looked for stories that were willing to fail for the sake of a story. I looked for stories that committed to the bit.

Emily Nemens: I spent a decade reading good stories—and saying no to most of them. What makes me say yes is different every time, though I think one commonality in editing, and which I found again while judging this competition, is realized ambition—a piece of writing that reaches, but that also is successful in its stretch. As for whether that reach is formal or conceptual, line-level or in its narrative bones, I’m agnostic.

Deesha Philyaw: I was hoping to be surprised. I was looking for subversion—of status quo, expectations, the usual tropes. And I was also looking for voices that would grab and hold my attention.

Catapult: Were there any big surprises?

SOM: “The Chicken” undid me so completely that at times I began to wonder if I too was a chicken, and then “Beat by Beat”—ach!—for days after I was left wondering if worm was god or god was worm or if the difference even mattered. This kind of existential alchemy is the mark of a great story.

EN: “The Cacophobe” knocked me flat—I was so impressed by that wild narrative voice. It was a bit of a slower burn when it came to “A Wedding in Multan, 1978,” but then I began to recognize all the subplots, context, and conflict that Majeed is able to fit into the confines of a story, and really saw the feat of it. And then there’s “Beat by Beat”: Shannon reminds me how much wonder, how much joy this world can hold.

DP: “For Future Reference: Notes on the 7-10 Split” was a big surprise. I read the whole story in one sitting, which is extremely rare for me. I couldn’t let it go—I just couldn’t let that character go—until the very last word. And then I immediately read it again. Another surprise: “The Cacophobe.” Reading it, I felt like Alice in Wonderland, like I was tripping. The humor, the delicious language, the absurdity, the twistedness, the suspense . . . so satisfying.

Catapult: Did you notice any recurring patterns/themes/subjects among the stories you read? If so, do the final selections reflect those larger patterns/themes, or push against them in some way?

EN: So many characters were looking for connection—no surprise for stories written and published in a pandemic. I also noticed an accumulating discourse around class. Many of these writers are thinking about disparity and opportunity, mobility and precarity.

SOM: Many of the stories felt written on the edge of an edge of an edge of a world. As Emily said, there was often a connection being sought—like a hand reaching out into a kind of nowhereness and hoping a hand might reach back.

Catapult: What was it like to come together as a group to discuss and decide on the twelve winning stories?

SOM: I loved how we listened to each other, and it was just such a pleasure being in the presence of such brilliant writers and deep readers. I loved hearing which stories tugged most at Emily and Deesha’s hearts (and why).

EN: These ladies were great—intelligent readers, enthusiastic advocates, and cogent debaters (when it came to that). We had to make some tough calls, but even then, I enjoyed the process. Lucky for us that we got to pick a whole book’s worth of winners! It might have gotten messy if we’d had to whittle it down to one.

DP: I thoroughly enjoyed working with Emily and Sabrina on this. We simultaneously embraced the magnitude of the task at hand and had fun with it.

Catapult: Can you share a bit about your first published pieces, and which ones felt like big breaks?

DP: I have a few “firsts.” Two long-defunct online lit journals published two stories of mine in the early 2000s. I don’t really count those because I don’t know anyone who read them! There was no social media, so I couldn’t share them. So I consider a story I wrote, titled “Bomani Jones,” to be my first published story. It was published in 2008 in a special Black women’s issue of pms: poem.memory.story , a literary journal based at the University of Alabama, Birmingham. My story appeared alongside work by literary giants like Lucille Clifton, Elizabeth Alexander, Yona Harvey, Nikki Giovanni, and Edwidge Danticat. When I received my contributor copy and saw that roster, I literally gasped. As far as big breaks, I’d say having essays published in The New York Times and The Washington Post felt like a game changer.

SOM: Many years ago (2001?), I remember William D. Waltz at Conduit accepted a group of my prose poems, a collection of small boxes that used what I thought only prose could use to make a poem. It felt like I had found a home inside those boxes, those squares and rectangles. I’ve always loved the violation of separation (like the separation of prose and poetry), a holy transgression, the impossible form. And that Waltz said to those early prose poems—okay, you can live with us too—that felt like everything. What has been the biggest break, though, has been my column, Happily , (in The Paris Review ). Writing a monthly essay, being edited by the brilliant Nadja Spiegelman, and working on a deadline has changed my entire relationship to what I ever felt I was capable of doing.

EN: I moved across the country for my MFA—going from Brooklyn to Baton Rouge felt a bit like getting dropped into a dunk tank. I had a hunch I wanted to write about baseball in grad school, and I took my first crack at it in this flash-fiction contest hosted by Esquire and Aspen Words. I couldn’t have been in Louisiana for more than two months when I got a call that my seventy-eight-word short story was a finalist, and they were going to fly me up to New York to workshop the piece with Colum McCann. We edited those stories like poems—every syllable counts when you’re working so small—and then had a nice celebration. That experience gave me such a boost; it felt like an assurance that I’d made the right decision to uproot my life in order to prioritize fiction, that I could write about baseball in my own sidelong way, and that New York would still be there even if I was operating elsewhere. Of course, it was a much longer journey to The Cactus League —I was working on that novel for over eight years—but what an auspicious beginning.

Catapult: What words of advice or encouragement would you share with this year’s winners, and to early-career writers more broadly?

SOM: I believe everything has value, everything. It’s just a question of sticking with it. I think that if you stay with something long enough, it starts to talk to you. If you care about something for long enough, it starts to bloom.

DP: I’ll offer the same advice a wise writer, Debra Dickerson, offered me twenty-plus years ago. It wasn’t what I wanted to hear, but it was what I needed to hear. She said, “Stop worrying about getting your writing published and worry about getting better at writing.” Take your time. Invest in your curiosity and growth as a writer. Hone your craft. Don’t be like the folks Toni Morrison talked about who “don’t want to write; they want to be authors.” Do the work.

EN: I’d second everything Deesha said—you really need to love the process to make a sustainable, healthy practice.