Don’t Write Alone Interviews

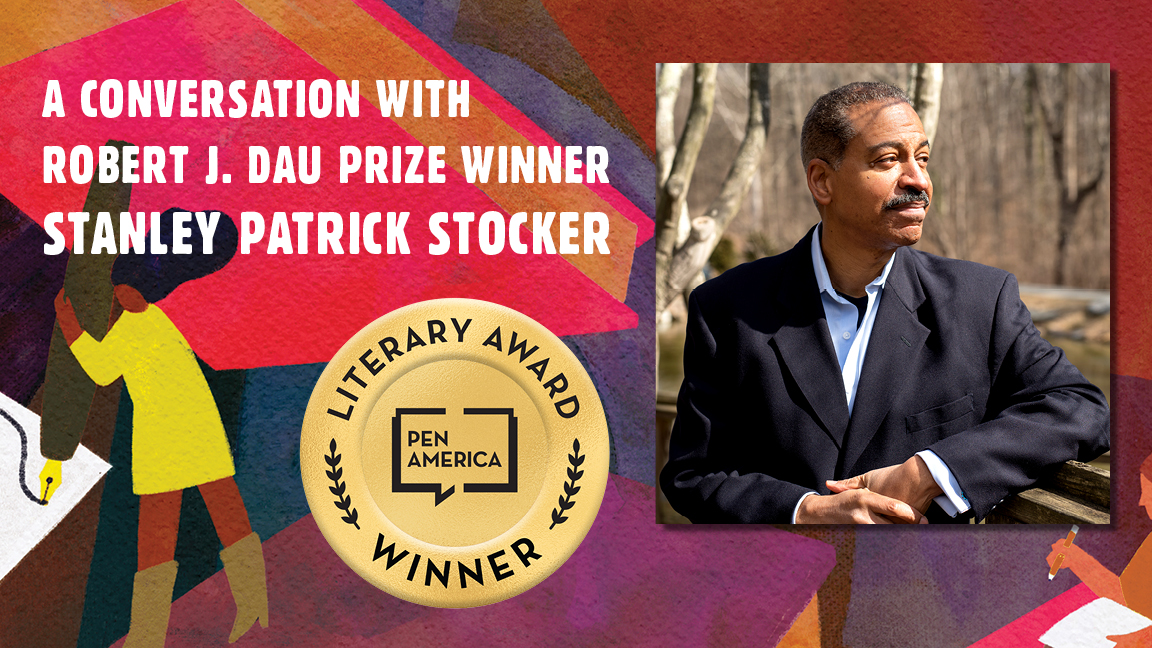

A Conversation with ‘Best Debut Short Stories 2021’ Author Stanley Patrick Stocker

“Good things happen when you keep at it.”

Best Debut Short Stories 2021: The PEN America Dau Prize is the fifth edition of an anthology celebrating outstanding new fiction writers published by literary magazines around the world. In the upcoming weeks, we’ll feature Q&As with the contributors, whose stories were selected for PEN’s Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers and for the anthology by judges Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, Kali Fajardo-Anstine, and Beth Piatote. Submissions for the 2022 awards are open now .

Stanley Patrick Stocker’s fiction has appeared in Kestrel and Middle House Review . He received an Individual Artist Award in Fiction from the Maryland State Arts Council. Originally from Philadelphia, Stanley lives with his wife and son in the Washington, DC, area, where he practices law. A graduate of Amherst College and Harvard Law School, he is currently working on a novel. He can be found at stanleypatrickstocker.com.

“The List” was originally published in Kestrel.

Not long after the accident, my sister Claire and I took a walk down by the river when the leaves were just beginning to turn. This was back when my wife, Eunice, was still barely getting out of bed in the mornings, and Claire had come down from Ohio to help out. As we walked, she said the soul drops down into the body anywhere from six months before birth to one month after. In the latter case, she said, it often hovers above the child, trying to decide whether to come down. I just gave her a look, and we walked on in silence, the leaves crunching beneath our feet. To be fair, she’s been into that kind of thing since we were kids. When my friends and I were in the basement smoking weed and listening to the latest Earth, Wind & Fire, she was up in her room with her girlfriends, trying to figure out what it meant if your rising sign was in Cancer. Later, after college, she became a serious metaphysician long before it was popular: crystals, a miniature pyramid in a corner of her living room big enough for her to sit beneath and “listen to the vibrations of the earth.” Now she’s got a decent real estate business with a Reiki practice on the side. Anyway, it sounded like so much mumbo jumbo to me. I’m a college professor, for God’s sake.

The death of the narrator’s daughter is central to the story, and yet we are given very little information about her death and the circumstances surrounding it. Was this always how the story was constructed? How did you decide what to reveal and what to withhold?

When I thought about writing the story, I immediately thought of Hemingway’s short story “Hills Like White Elephants.” I vaguely remembered how part of the story’s power was due to the way some central issue was hinted at but not addressed directly. Then I went back and reread it and saw that the central issue seemed to be the question of whether the woman would have an abortion, but it’s never mentioned explicitly. In my story, I wanted the death of the daughter to have that same kind of power by virtue of not being fully revealed. I wanted to show not the death itself, but the effect it has on the husband and wife and their marriage in the same way that the unspoken thing has an effect on Hemingway’s characters.

Incidentally, midway through the drafting process, I also tried a structure in which I listed ten numbered works of literature and music spaced throughout the story. That didn’t quite work, so I eventually went back to the original structure. But omitting the details of the daughter’s death was something I wanted to do from the very beginning. Maybe there was a bit of self-protection there too. No parent wants to focus too much on the worst case scenario.

Where did you find the idea for this story?

It found me. My wife and I were looking to hire a new babysitter for our then three-year-old and I was feeling anxious about entrusting my child to a new person and my mind went to a worst case scenario. Then I thought, Oh that would make an interesting short story . My second thought was that I couldn’t possibly write such a story lest I jinx my family somehow. But in the end, I thought, that’s one of the things that writers do—write about things that scare them. Turns out after I completed the story, that particular anxiety pretty much disappeared, which reminds me of the line that Melville wrote to Hawthorne after completing Moby Dick : “I have written a wicked book, and feel spotless as the lamb.” I think when writers do their duty and write what demands to be written, there can be certain psychic as well as artistic benefits.

How long did it take you to write this story?

I completed the story in about two months and then shopped it around, but I came to realize that I wasn’t quite satisfied with the ending. A couple of months later I added a different ending that rounded out the story much better. So, all in all, about two months of drafting in the evenings and during the commute to the office, followed by a couple of months of tinkering with the ending. The seeds of the eventual ending were already there in the story. I just had to go back and listen closely.

During the time that the narrator and his wife were struggling to conceive, we learn that the narrator compiled a list of songs, poems, and films that made him feel better. What is it about art that comforts the narrator during this time, and in what way has it been a balm for you?

That part was borrowed directly from my life. I kept just such a list when we were going through the stresses of fertility treatments before our child was born. It helped me to have some beauty near me. When you experience something of great beauty—say Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address or Ellington’s “Concerto for Cootie”—it’s like you visit a place that is outside of time. The present and its hardships fall away. It may only be for a few minutes, or however long it takes to read something or listen to a piece of music, but you emerge refreshed and fortified. And I don’t mean that as mere escapism. Art can be a reminder of the beauty at the heart of life, or at least the potential for beauty, and I think we respond to it because it already exists within us. Otherwise, I don’t think we’d recognize it when we encounter it. It activates something already within us like the way a bell is struck. We are the bell and great art strikes us.

How has the Robert J. Dau Prize affected you?

Receiving the Dau Prize has been a great encouragement. I’m very grateful for it. I’ve been laboring on a novel for quite a while. During the day, I practice law, and I write at night after we put our son to bed. It was four years ago that I felt compelled to write the story that went on to win the Dau Prize. It was gratifying to have something fruitful come out of the time away from the novel. As the poet Paisley Rekdal says, “Writing is an act of patient endurance; it is a spiritual pursuit, and curiosity is the god that oversees it all.” For me, the Dau Prize, and any recognition at its best, encourages that patient endurance, that spiritual pursuit, that curiosity. On a practical level, the cash award was great for enabling me to build a writing website since I’m not very tech savvy. The added bonus of the Dau Prize is having eleven other debut writers to share this experience with. It’s great because we’ve met virtually and exchanged emails to discuss craft, writing opportunities, and the writing life generally.

What are you working on now?

I’ve completed my revisions to the novel and I’ve just started querying it. The novel is set in early 20th-century Mississippi. A thirteen-year-old boy goes on a harrowing search for his father, who has abandoned him in despair following the sudden death of his mother. The querying process is my main focus right now. After that’s done, I want to get back to some short stories.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received and why?

The best writing advice I’ve ever received is something I read by Bonnie Friedman that I keep on a scrap of paper, just above the light switch in the room where I write. I put it there so I’ll see it every day: “Successful writers aren’t the ones who write the best sentences. They are the ones who keep writing.” It’s a reminder that good things happen when you keep at it.

Finally, where do you discover new writing?

I subscribe to a number of journals and magazines. Journals like Kenyon, Electric Literature, The Common, A Public Space , and Kestrel where — “The List” first appeared — are great places to find new work. Now I can add the PEN/Dau anthology to that list. Book Twitter is also a great resource for finding new work.