Places At Work

The World of Transshipment, Where One Glitch Can Lead to Chaos

I couldn’t stop thinking about what I would do if something went wrong. If I made a mistake, my son and I might go back to being homeless.

When American produce goes to Asia, it travels by sea. Tons of peaches, potatoes, and canned corn are packed onto a vessel which sails from our west coast to a port in the south Pacific. The voyage takes about sixteen days unless there are rough seas, mechanical issues, or tsunamis.

There are no direct routes for these vessels.

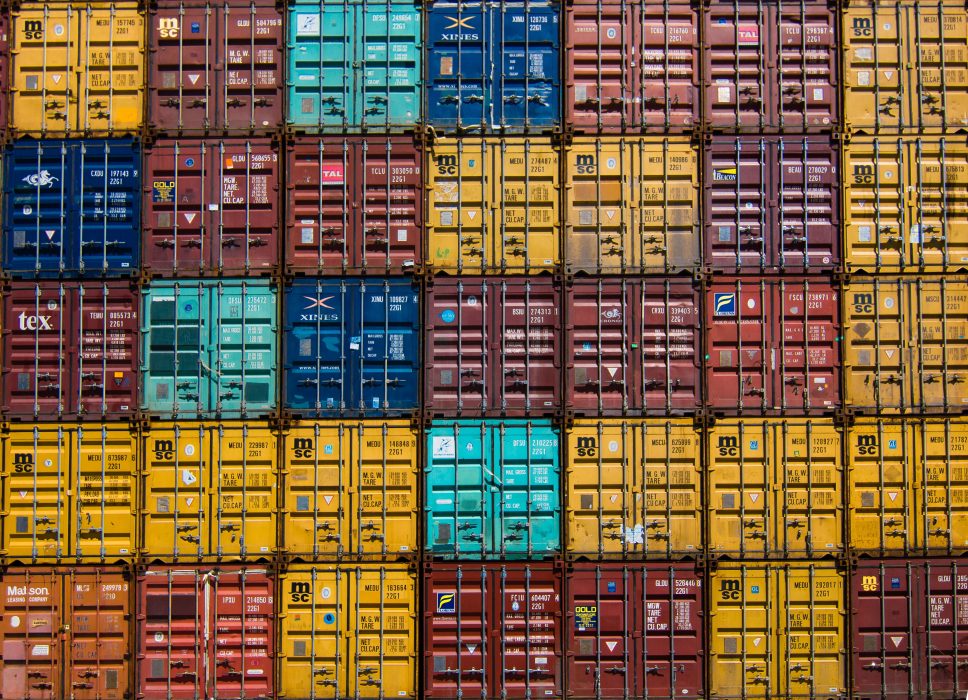

Kaohsiung, China is a major transshipment port: a massive transit hub, where containers are shuffled from ship to ship. Cargo traveling north will continue up to Busan, South Korea. Containers bound for Manila, Philippines are put on a vessel sailing south. It should work like a well-oiled machine, but it doesn’t. Imagine this: The terminal secretary, who is tired of looking at columns of numbers, keeps rubbing his lazy left eye. His first language is Cantonese. The English words on the seaway bill, the customs documentation, the halal and USDA certificates, and the courier slip assuring certification of free sale crawl like misshapen ants across the thin white paper. He confuses the routing slip and diverts the container to Busan. By the time the mistake is discovered, the container is one week late into its port of unlading, and the shipper is furious and screaming at the freight forwarder in Thai on the phone.

It’s not the end of the world, of course. This problem can be fixed: All problems, in this industry, have a solution. The only variance is the price tag.

*

In April 2013, a temp agency placed me in a job at a freight forwarding company. It was temp-to-hire, and better than working at yet another reception desk, getting breathed on by yet another male boss. Every day, I sat on a yoga ball while drinking coffee and entering data into electronic forms. Freight forwarders are middlemen in the trade industry. They create documents, organize travel and transportation for cargo, and make sure that whatever is ordered arrives more or less on time. They are like travel agents for whatever people want to buy, booking passage by air, boat, train, and truck. It is not glamorous, but it is essential. People have to eat. The supply chain stretched out on both sides of me, conveying Russet Burbank potatoes from Simplot’s massive commercial farms to the people who would dip them in ketchup on the other side of the planet.

The maritime industry is, in so many ways, a holdover from another time. A lot of the jargon has persisted for centuries, developed from French or Old English roots: demurrage, bill of lading, drayage, consignee. Many of the laws governing how we import and export cargo date to medieval times or even earlier, their codes as inflexible as a vow of chastity. Labor contracts are negotiated with the care older civilizations put into their royals’ nuptials, and are in many cases based on alliances, enmities, and grievances older than the countries that participated in them.

I quickly learned the terminology and the tariffs, and after a trial period, was given a small raise and my own desk in the export department. My cubicle was next to the windows on the ninth floor of a tall building in the business district. I started filling the drawers with folders: green, yellow, orange, and plain manila. Each color was coded to a different destination.

I knew nothing about being a clerk, or shipping cargo. As a single parent, though, it’s hard to pass on anything that manifests a regular paycheck and insurance coverage. During the week, I dropped my second-grader off at his classroom early and took the bus to work. On my days off, we walked down by the harbor, and I pointed out the ships and cranes to him. My job was everywhere, all around us. I was suddenly aware of a vast web of interconnecting markets, tariff codes, weather patterns, union agreements, ports, vessels, trucks, warehouses, terminals, and the thousands of people who operated the moving parts of the business of serving McDonald’s french fries.

I pinned a map of the other side of the world next to my desk, with cities dotted in red marker: Jakarta, Manila, Kaohsiung, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Tokyo. They were places I’d never be able to visit; I barely earned more than minimum wage. But my son and I could afford a tiny apartment now, and at least we were off food stamps. When he asked me where the ships went, I told him about the beautiful countries across the sea, knowing that I’d never make enough money to take him there myself. Still, for the first time in a long time, I had a sense of stability.

While I should have been happy, I couldn’t stop thinking about what I would do if something went wrong. If I made a big mistake, I’d lose my job. My son and I might go back to being homeless. Every week, I tallied up my hours on my timesheet and worried about our future. The containers I shipped were worth tens of thousands of dollars: a house’s down payment, a year of college, a fairy-tale wedding. I was knee-deep in other people’s revenue, but my son and I still collected cans for the deposit and ate canned beans and ramen at the end of the month. We never ate at McDonald’s.

*

I’m amazed that a small serving of fries is less than $1.50. It costs tens of thousands to grow, prep, store, transport, and serve a single container of frozen potatoes, not to mention maintain the infrastructure that sustains the McDonald’s business. Every middleman in the farm-to-consumer pipeline takes a small cut.

My company made less than ten dollars per file; others, like the trucking companies we hired to pick up extra containers, charged by the load size and the mile. The prices on the McDonald’s menu are padded to accommodate every fee and charge those containers of potatoes pick up on their way to their final destination. You’re not just paying for the fries. You’re paying for the entire supply chain.

Nothing commercial is just the thing that it is. Everything we eat, buy, wear, touch—the chair you’re sitting on, its faux-leather cushion, the pressed wood frame, the cotton in the thread that holds the padding together, the chemical glaze and dyes that give it a “real wood” look, and the cardboard shapes that once held it in its shipping carton—all come from different places. The everyday objects in your life, from your birth control and multivitamins to hair products and cooking utensils, are the result of commercial confluence. All the necessary materials flow through the ports of the world, and all the middlemen skim their cut.

And it all works fine until, suddenly, it doesn’t.

*

Something always went wrong. Sometimes it was as simple as two transposed digits in a container number, or the wrong seal, or a missing certificate. It was easy to miss an error like that, with such a high volume of shipments. I lived in constant fear of making too-expensive of a mistake; I couldn’t risk being less than perfect. I reviewed documents for typos until my eyes ached.

The shipments of fries were almost identical: Each one was 1,302 cases of fries packed into a forty-foot long steel container with a reefer generator mounted to its side. Its internal temperature was set to negative eighteen degrees Celsius, sliding bolts double sealed each shipment, and customs paperwork fixed over the door with clear packing tape. But they were shipped by humans. People in trucks, warehouses, and offices, standing on the dock with a clipboard. Fallible beings, who got stressed, tired, and overwhelmed by the high volume, were at every point in the supply chain. A mistake by any one of us could snowball into a massive problem for all of us.

As the 2015 holidays approached, exporters tripled their orders. Christmas meant big business, even in non-Christian countries. When a truck of frozen fries arrived at the port’s warehouse, the reefer was supposed to be weighed, accounted for on the manifest of departing cargo, unloaded, and then plugged into sockets again so that the cartons inside wouldn’t start to warm up. There was a limited number of sockets for these reefer containers, both in the holding area and on board. Big companies like McDonald’s got the lion’s share because they could afford to outbid smaller competitors.

The longshore union who worked the port knew this, and negotiated their labor contracts accordingly. The union was paid by the plug; the port, by the ship and by the load. Everyone got their cut.

As Christmas approached, the ports started to slow down. The International Longshore and Warehouse Union was in its ninth month of contract talks, and everyone was getting tired. Portland’s longshore union, in solidarity with the other West Coast port workers, suddenly wasn’t sure whose job it was to plug, unplug, and monitor the reefer containers. Was it the longshoremen, or the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 48? Who would get paid for the job? Who would enforce the port’s standards of safety? If the union said yes, the port said no.

While they argued, the reefer cubes sat unplugged at the port, leaking as they melted, the potatoes inside turning to soggy mush. My days went from a standard nine hours to twelve or fourteen. I dreamed about metal, cranes, and shipwrecks. It went on for months. Our office mantra became nobody dies if they don’t get their fries.

The unions slowed down and the market dipped. In Portland, you couldn’t get certain products once the store had run out: Tapioca, Asian imports, and Christmas toys were incredibly expensive or impossible to find. Our inability to move those containers made international headlines. The Pacific Ocean, momentarily relieved of the high number of cargo ships agitating her waters, began to rebound. Bizarre creatures came to the surface to do their bioluminescent dance; a species of nautilus, feared to be extinct, was spotted by a researcher in Papua New Guinea for the first time since 1984; a Blue Dragon Sea Slug washed up on the coast of Australia.

For me, every waking hour was stressful, a constant rush to make sure that I didn’t drop one of the plates I was spinning. It was dark when I woke up in the morning, dark by the time I got home. My job ate my life in greedy bites. Each day, I felt like I saw less of my son and the world outside my office. The overtime was turning me from a mother into an office machine. One day, on the ride home after work, my son looked at pictures of the rare sea slug on my phone while I tried not to nod off.

“Mama, it looks like a Pokémon.”

When did he learn about that? I wondered.

I was so tired that I almost slept through the alarm the next day. Again I got up, dashed to school in time for my son to get breakfast in the cafeteria, pried myself out of his hugs, and rode the bus across town, praying that I wouldn’t be late to my job in this industry that devoured everything it touched. That morning, while taking yet another cup of coffee to my desk, I flipped open yet another yellow file for yet another container of fries and decided that I didn’t care anymore. It just wasn’t worth it. The things I was missing were too precious to me.

*

I left before the unions settled with the port. Things only got worse. The last container ship company, Westwood, left the port in May 2016. That was the end of trans-Pacific service from Portland to Asia. By then, I had taken a job with set hours and better pay across town at the Portland Japanese Garden.

I was given a key to the Garden, a jewel tucked into the Northwest landscape. On my first day, I stood by the stone pagoda tower lantern and watched my breath fog. The surrounding quiet space felt like it had been there for millennia. The plants were simply from the places they were from. Nothing was for sale. There were no middlemen, just moss, koi, and trees.

aThe silence muffled the busy world outside the garden’s walls, as though I was packed in insulation. I found something I’d been desperately missing: harmony. The Garden had deep roots. It could not be packaged, trafficked, or sold. I’d left the ports and sailed for the shore of my own life, finding someplace safe and green. I exhaled. How could I put a price tag on this?