Fiction Short Story

Our Sleeping Lungs Opened to the Cold

What was it about us that disturbed the clients so thoroughly?

They didn’t know that we had changed. When they created us, they named us for precious stones—Sapphire, Opal, Ruby, Jade. We were created for adoration, indexed behind glass. We were created sleek, glowing, hair lustrous as hallucinations; our tails gleamed as if each scale was lacquered by hand; we were created graceful and ripe—Diamond, Garnet, Emerald, Pearl. When the restaurant was open we swirled behind the glass walls, floating spectacles for the tables of dignitaries, well-heeled couples, high-rollers giddy with luck well spent; we spun languid corkscrews through the shining water. At night when the customers were gone, when the last waiter would hang up his apron or the chef his white hat, we would sink to the bottom of the aquarium and sleep with limbs and tails entangled, a fluttering octet, our breaths vibrating through ourselves and each other and the water, meeting the hum of the purifier in a somnolent fugue.

The adjustment was only incremental—a reduction in the chemical that kept us docile, to accommodate the fish they released into the aquarium. It did make for a more striking display, having other aquatic life to complement our beauty; it brought new wonder to the eyes of the clientele, deepened their love. They would order another glass of wine, and then another, mesmerized; the restaurant’s opening hours stretched into the early morning. A photograph of Ruby with yellow tangs nestled in her billowing hair made the cover of National Geographic, and the restaurant was fully booked for the next six months.

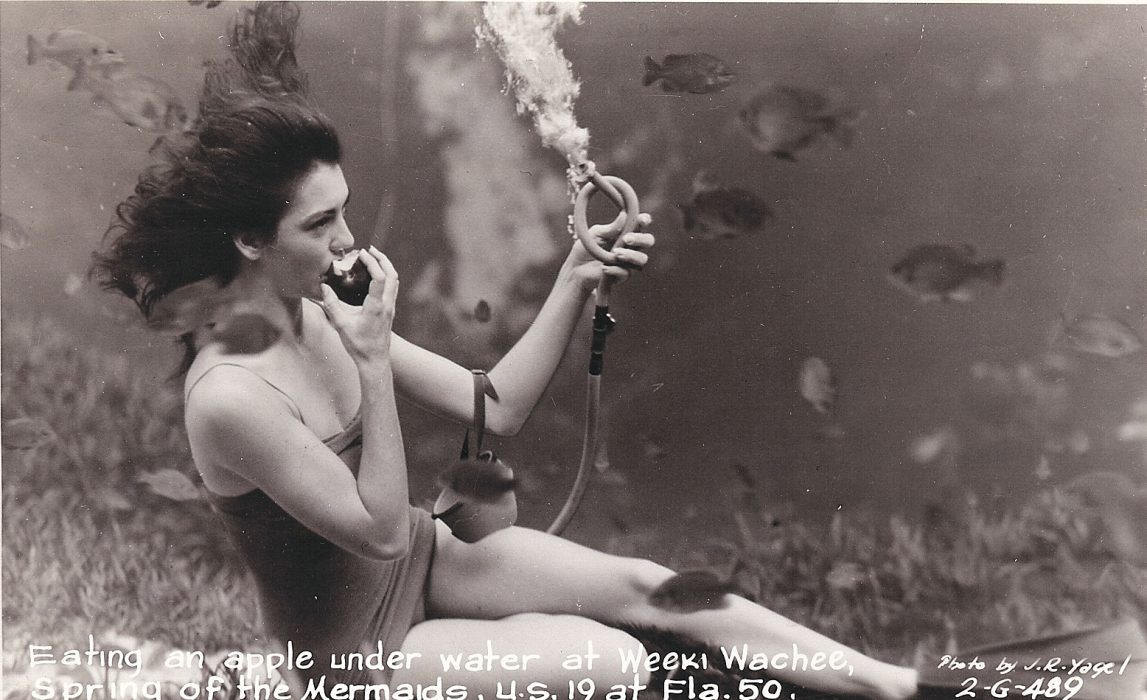

We believe that the aquarist truly loved us. He would visit us once a week with his wooden box that unfolded on zigzag hinges, kneeling beside the hatch to collect a trembling sample of water in his vial. On rare occasions, he would arrive in a black, oily skin with ungainly flippers and breathing apparatus—would plunge into the tank, scrape algae or calcium from the rocks for study. Only a few of us ever witnessed this ritual directly—Sapphire was the first to have seen him do it—because they would increase the dosage of the sedating chemical each time the task was necessary. In fact, any time some drastic change to the aquarium occurred—the last of which was the introduction of the fish—we would be lulled to sleep by the sedative slipping invisibly between our gills. The aquarist never touched us, but we loved him.

We all dreamt about the aquarist. Garnet described one dream in which he stood for a long time at the edge of the hatch—not in his vulgar skin-tight suit, but in his regular trousers and navy blue shirt with the cuffs folded up to the elbows. He knelt to untie his shoelaces and pull his shoes from his feet, and then his socks. Garnet admired but did not envy his toes, flexible stumps of coral, crenelated like teeth. Last of all, he took off his spectacles and folded them next to his shoes – and then, with this last piece of glass between them removed, he slipped into the water. For all his gracelessness, he was beautiful, his arms hovering in surrender, dangling toes pointed, dancer-like, to the aquarium floor. Garnet swam to him. He was warm, she said. A man-shaped membranous sac of blood.

Later, we would conclude that the aquarist didn’t foresee the cumulative effects of reducing the sedative.

We started eating the smallest fish first—the damsels, gobies, blennies. We liked to feel them darting, wriggling in the caves of our mouths, before we swallowed them whole. Then the larger fish—the angels and basses—when Emerald discovered the pleasure of fine bone snapping under teeth. We would wait until the customers were gone and plot which fish to take next, to pass between us and feast upon, their slippery flesh and jellied eyes, scales flaking from skin, meat peeled from the vertebral column. We always marveled at the way their blood disappeared so quickly in the water, assimilated into benign clarity.

Our bodies were not so fragile: they thickened in glory. Collarbones sank beneath the luxurious swell of flesh. We liked the way the water held us, our new presence within it; we were increasing in corporeality and palpability, more vowel than consonant; we became orchestras. Our scales, which formerly terminated at our hips, began to multiply on our waists, then our stomachs, then our breasts, then our arms. The webbing between our fingers slid closer to the tips; our pupils fattened beyond the grasp of our eyelids.

The customers did not enjoy our transformations as much as we did—there was a dissonant modulation in their stares, a curdling of the irises—but, as we grew, life outside the aquarium shrank in importance, inconsequential as the blood of our prey. What delighted us was each other, our turning into something less hollow. We no longer adhered to the rhythms of the restaurant, the customers’ comings and goings—if we desired sleep, we slept; if we desired privacy, we retreated to the furthest reaches of the aquarium, huddled in molluscular indifference.

When we did stare outward, it was deliberate, silent. We liked to lock eyes with a customer about to eat; we liked to watch for the quivering pause of the fork to the mouth.

By the time the proprietors increased the frequency of the aquarist’s visits, it was too late. Most of us had developed scales up to our chins; Diamond’s scales encased her head almost completely. We were arcing towards our metamorphic conclusion, following the imperative of our blood and bodies. We could pull our hair in fistfuls from our scalps; the untethered strands would float away like undulating harp notes. On the surface, the hair would be less magical, gathering thickly near the hatch, where the aquarist would be waiting with his zip-lock bags. Eventually, the sight of us would become so unnerving to the customers that the restaurant was forced into what was soberly reported as—and what the proprietors handwringingly hoped would be—a temporary closure.

At first, we wondered: What was it about us that disturbed the clients so thoroughly? But then Opal refracted the question: What was it about us that they so loved to begin with?

In those final days when the restaurant was closed, the aquarist was our only visitor. He’d created a makeshift lab in one of the plush booths, testing sample after sample, as if the nutrients in the water would take pity—would join cells to spell out for him an unambiguous resolution on the microscope slide. The aquarist refused to follow the proprietors’ suggestion to sedate us—he didn’t want to harm the fish—and it is this kindness, this devotion to the living, that permitted our migration.

We needed to escape while we still had arms. The restaurant was embedded in the casino complex, and had no outwards-facing windows. And yet we could hear the storm, like a baby in the womb might hear the voice of her mother, and the voice said: This is the time.

Jade had been the last to see the aquarist operate the hatch door from the inside. One by one we clambered out, those still in the water helping to hoist the climber. On the gangplank our gills collapsed; we breathed for the first time with mouth and lung, overwhelmed with sensation, the strangest of which was wetness, for surely we had always been wet, but separate from our habitual context our dampness acquired some more pungent meaning. The sound of us grappling for oxygen supplanted the throb of the purifier as our pulse; we were all at once irregular, out of time, cold and trembling and porous.

Transplanted from the water, our bodies lost fluency; we fumbled with elbows bent amphibian-wise. Our skin opened from the clamor of new textures, from the metal grid of the gangplank to the carpet of the restaurant to the marble tiles of the grand foyer; we left a painful trail of blood and hair and chipped scales. We crawled, clustered as close as possible in our octet, allowing the fatigued ones to crest for a time on the ones who could move, sliding over and around each other in a reinvention of our former effortless flight.

We couldn’t say if we truly expected to survive. We were only following the sound of the storm, the churning of rain; we were making an offering of faith to our morphing bodies. We expected more resistance, but the casino patrons we encountered recoiled from us, fleeing from our path as if we were carriers of some evolutionary glitch, our scuffling forms neither fish nor human nor mermaid.

We toppled into the storm, still clutched in our octet, into the rain’s brutal percussion; the streets were slick and dark like the aquarist’s diving suit, the moon a shucked oyster. There was a place where the rain struck an expanse of water, we were sure of it; we were sobbing—another new sensation—heaving our tails, leaden as honesty, across the bicycle path, the soaked grass, the embankment of rocks.

We don’t know which one of us entered the water first: Perhaps we tumbled into our new home knotted and united, blooming in the refound weightlessness. Or: Perhaps we lost consciousness on the rocks, and the river’s oscillations, in their slow, benevolent way, coaxed us into its embrace. Parted our gills, arches flexing like cathedrals.

Where we are now, the light comes from above—we must crane our necks to look outside ourselves; we must break the surface to see clearly. Where we are now, there is such a surface to break. Where we are now, we are not observed, or exalted, or feared: We glide and somersault and feast; the bubbles of our breath drift skyward like arpeggios. In this water, soupy and fecund, there is no watchful metronome of the purifier, no crosshatch of gazes, no glass vertices. This gentle darkness, this soft temple. This loving body, unspooling from the harness of manmade meaning.